By August 1918, the tide of the war was turning, with the launch of an Allied offensive in Flanders and the last Zeppelin raid on England on August 5th.

Meanwhile, rationing and shortages permitting, life carried on in Somerville. The 1918 SSA Annual Report was being prepared for publication, albeit in a shortened version and thanks to the foresight of the Treasurer, who had arranged a supply of paper with the printers beforehand sufficient for 24 pages. The 1918 issue was described as supplementary to the 1917 report.

The issue did include a further list of Association members and their occupations, with some unusual entries.

Mary Leys was an officer in the recently formed WRAF.

Hilda Lorimer was working for the Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office. Her sister Florence, who had read Classics at Somerville, was working at the British Museum as secretary to Sir Aurel Stein on the Indian Archaeological Survey of Srinagar, Kashmir. (Her next job, which she took up in 1925, was a buyer in the oriental carpet department of Peter Jones and John Lewis).

Dorothy Townsend was a journalist. Audrey Priestman was Head of the Machinery Census of Textile Trades of Great Britain. Hilda Skinner was working for a firm of Average Adjusters in the City and Frances Lupton’s entry was ‘Autumn 1918, to train as a solicitor’.

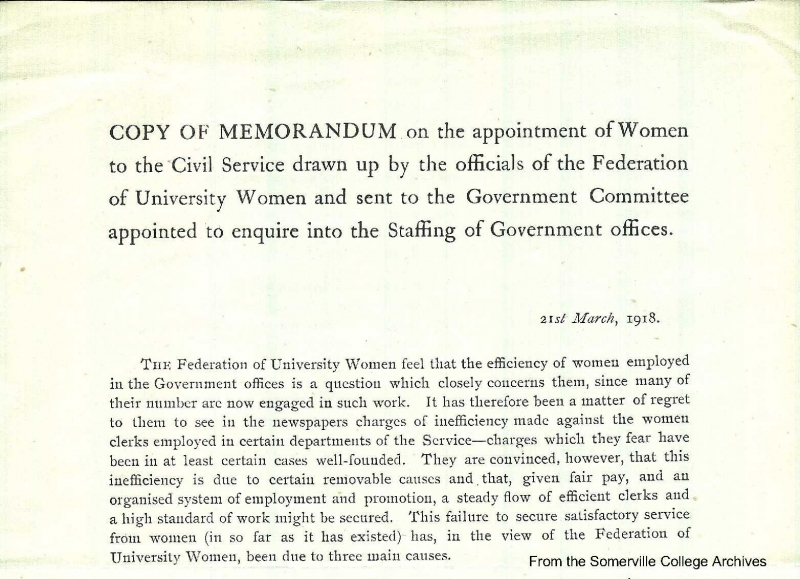

Women were employed in many professions previously reserved for men. Some, like the Civil Service, depended on them but there were considerable shortcomings in the haphazard nature of their employment – most had temporary posts and there were no proper systems of recruitment, promotion or training. Support for the work of these women was not universal, with accusations of inefficiency in the press prompting the Federation of University Women to send a memorandum to the Committee on the staffing of Government offices addressing this issue.

The Machinery of Government Committee, established by the Ministry of Reconstruction in July 1917, published its report at the end of the 1918. It found that the experience of the previous four years had resolved any doubts on women’s suitability as civil servants and included the statement:

“the absence of any substantial recourse to the services of women in the administrative staffs of Departments, and still more in their Intelligence branches …… has in the past deprived the public service of a vast store of knowledge, experience and fresh ideas, some of which would, for particular purposes, have been far more valuable and relevant than those of even the ablest of the men in the Civil Service.”

A year later, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of December 1919 became law, the first legislation to enable women to enter the professions. It particularly addressed women in the law and in the civil service, although provisos in the act meant restrictions remained in place for several decades more.