Throughout the Great War, the number of Somerville students officially pursuing war work remained comparatively small. However, these were students, such as Vera Brittain, who had taken a leave of absence, most intending to return after a term, a year or at the end of hostilities. Still more students chose to leave college entirely, unable to continue their studies when so many of their contemporaries had been killed or wounded. One such was Margaret Philp, who left Oxford abruptly in 1916; her local regiment, the Gordons, had been ‘wiped out’ in action and she could not stand to take her degree in such terrible circumstances.

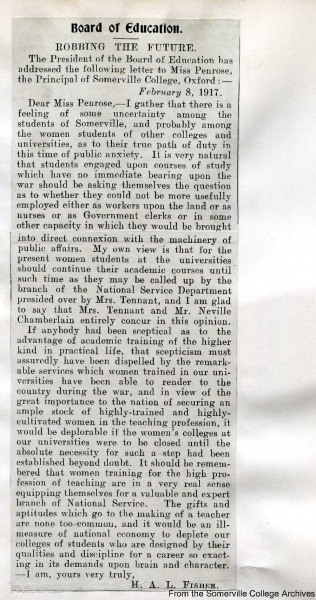

The Principal, Emily Penrose, was concerned at the number of students willing to abandon their academic careers altogether in favour of national service. The college and its members had striven to contribute to the war effort in any way possible. For Emily Penrose, that meant in addition to – and not instead of – academic pursuits. The country would require university educated men and women in the future. In completing their courses, students would be putting the needs of the nation above those of the individual. The recently appointed President of the Board of Education, H.A.L. Fisher, shared this point of view and was willing to do so publicly.

Fisher, the historian and fellow (and future Warden) of New College, Oxford, had long been a supporter of education for women and of Somerville College in particular. He had professional and personal links with the college. He became a member of Somerville’s Council in 1900 and served as its President from 1910 to 1913. His wife, Lettice Ilbert, the historian and social worker, was a Somervillian.

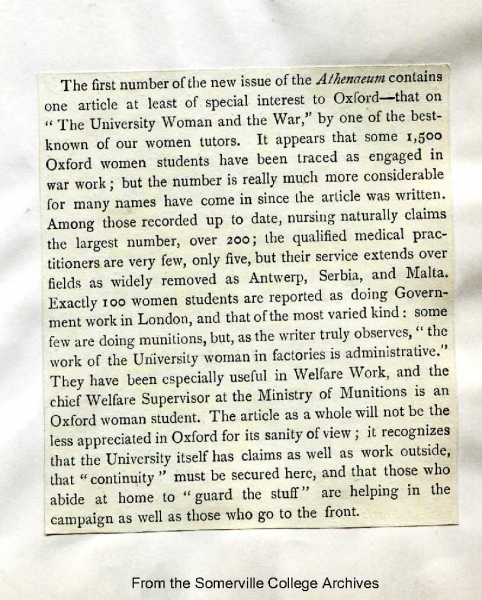

In December 1916, Fisher became a Member of Parliament and the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, appointed him President of the Board of Education. In a letter to Emily Penrose, published in the Times on 8th February, Fisher emphasised the importance of university-educated women to the war effort and to the future. He addressed students in person the following month, at the Sheldonian Theatre, and the Oxford Magazine carried further articles on the value of University women to the nation and to Oxford.

It is difficult to assess the impact, if any, of Fisher’s intervention; students continued to abandon their studies almost to the end of the war. One of the last to do this was Winifred Holtby in June 1918; having taken her first year examinations, she got permission to go to London, ostensibly to visit a relative, instead using the opportunity to enlist in the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps. For many of the ‘war generation’, their duty lay outside academia.