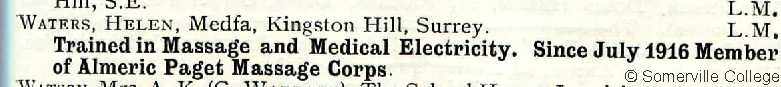

In July 1916, Helen Waters, a former English student at Somerville, joined the Almeric Paget Massage Corps (APMC), having undergone training in ‘Massage and Medical Electricity’. The APMC was one of the many voluntary schemes, established at the outbreak of hostilities, which went on to be recognised officially and eventually incorporated into the country’s response to the national emergency. 1916 was a pivotal year in the APMC’s transition from voluntary scheme to official service and by that December, it had become known as the Almeric Paget Military Massage Corps.

Physiotherapy was a comparatively new form of medical treatment before 1914 but at the outbreak of war, Almeric Paget, the MP for Cambridge, and his wife, offered to establish and run a therapeutic massage service, providing 50 volunteer masseuses to help rehabilitate wounded servicemen, without any cost to the Government. The first masseuses were deployed in military hospitals in September 1914; such was the demand that over 100 had been recruited by the end of the year and the Pagets had set up an out-patients’ clinic.

The changing nature of combat in the First World War, combined with developments in military technology, were reflected in the damage inflicted on the combatants. Trench warfare, machine guns and heavy artillery bombardments produced catastrophic injuries with high levels of loss of limb and, due to the muddy conditions, such severe risks of infection that, even if not lost, it was often necessary to sacrifice a damaged limb in order to save the patient. Once repatriated, injured servicemen could convalesce in military hospitals where massage and electrical therapy (stimulating the muscles with small shocks) became widely employed to aid recuperation. The success of the Paget’s clinic attracted the attention of the Royal Army Medical Corps and in 1916, the Pagets were offered a grant to run the massage departments in the large convalescent camps and military hospitals. By the beginning of 1917, the Corps had 1200 masseuses and its Military Masseuses were being sent to serve overseas.

Other Somervillians who worked in medical massage included Emily Kemp, one of Somerville’s earliest students and an intrepid traveller: she spent the whole war in France assisting the French army by organising two hospitals, running a canteen for soldiers in Verdun and, from 1916, working for 18 months as a masseuse in the French Military Hospital in Paris. Juliet Ogilvie also worked as a masseuse in military hospitals from 1915, as did Jane Worthington, who had been a nursing sister in civilian life.

The requirements of war resulted in advances in other areas of treatment and technology, including skin grafts and artificial limbs. Among the staff photographed for the 3rd Southern General Hospital’s souvenir album at the end of the war, the masseuses can be seen in their plain white aprons, one possibly wearing the insignia of the Almeric Paget Military Massage Corps.