“I can’t tell you how glad I am about the fine spirit of the imprisoned COs. I never feared that many of them would give way, but I hadn’t expected that they would actually have an effect like this on the outside world. I thought that was past influencing, for the time.” Leila Davies to Joseph Dalby

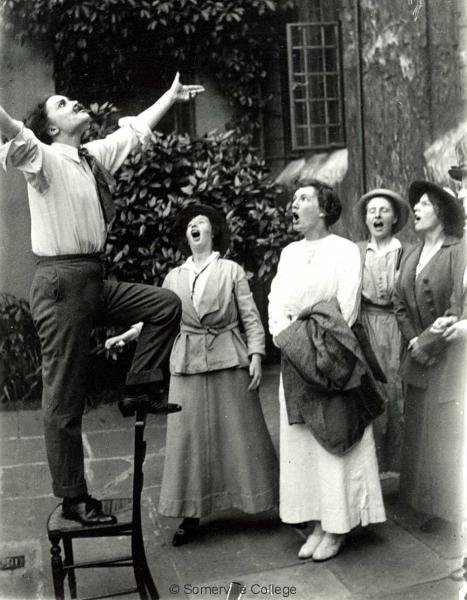

In 1916, Leila Davies was in her third year at Somerville, reading English. Her younger brother Philip (known as Tal) had gone up to Queen’s in 1915; an active socialist, he was also a conscientious objector (CO), incarcerated in the Cowley Barracks in East Oxford, which was used for the detention of COs from April 1916.

The Military Service Act had become law in March 1916, making enlistment compulsory for single men aged between 18 and 41, with certain exemptions, one of which was a conscientious objection to combatant service. Many thousands of men did object, on religious, political or humanist grounds and although some were prepared to take on non-combatant military roles or civilian work in aid of the war effort, there were also ‘absolutists’ who refused to do anything in support of the conflict. Conscientious objectors had to put their case for exemption before a local tribunal; if their case was rejected and alternative service refused, they could be court-martialled and imprisoned.

Conscientious objectors were judged harshly by the general public, condemned as cowards undermining the war effort by evading their duty to king and country. Their supporters were similarly vilified. For those awaiting court-martial, contact with the outside world was closely controlled, with correspondence censored and visitor access severely restricted. It was through Leila Davies that Philip was able to seek advice from Joseph Dalby, a family friend and member of the No Conscription Fellowship, regarding his absolutist stance. In Leila’s letters, she described the details of her brother’s detention and the wider issues influencing COs, also her own fervent support for their beliefs: “It’s a privilege for Tal and you and the others to be of that fellowship. You’ll be glad of it all the rest of your lives, and we shall be glad of it for you…. But meanwhile you’re having the heavy end to bear, and you’re paying the penalty for all of us, you few, because you happen to be young and to be men…. I feel half ashamed to be at large, when the only place fit for decent people of my convictions is prison.”

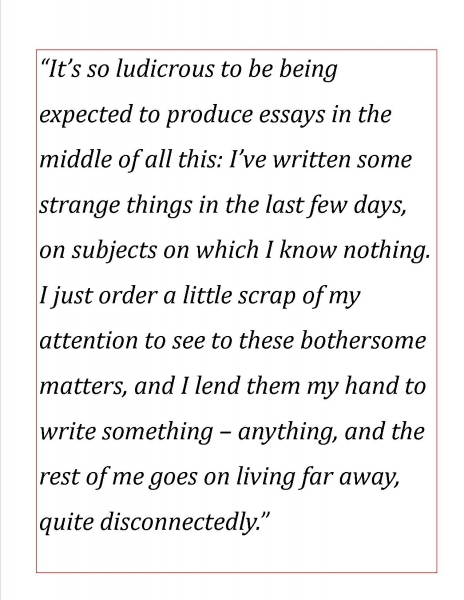

Academic work became an irritating distraction, as supporting her brother, and conscientious objection more widely, became the focus of Leila’s life. Philip Davies considered the court-martial to be a foregone conclusion and decided to proceed without a solicitor or any witnesses. He was sentenced to 3 years in prison. On his release, he did not return to Oxford and, as with all conscientious objectors, was denied the right to vote for five years.

With thanks to Bridget Davies.

Visit www.europeana1914-1818.eu for more family stories from the First World War.