By January 1917, the war was taking its toll on the home front. Shortages of food, fuel and staff were resulting in higher costs, at a time when money was also in short supply. Morale was low and for Vera Brittain, stationed at this time in Malta, letters received from home depicted a country struggling but determined to carry on.

At the college meeting of January 24th, Somerville students devised two novel ways to ‘do their bit’ – making their own beds and forgoing extravagant tea parties.

At the start of the war, Somerville’s domestic staff included 24 maids who lived in, with 10 daily women in addition; by January 1917, the number of maids had halved and the daily women numbered 7, falling to 6 half way through Hilary Term. Whilst the number of maids did not diminish at the time of the move to St Mary Hall in April 1915, their numbers plummeted six months later at the start of the following academic year and the revised living arrangements (and resulting shortage of accommodation) no doubt contributed to this. A number of (mostly) long-serving maids remained with the college but some, such as May Drew [see blog June 1915] chose to leave, wanting to undertake war work.

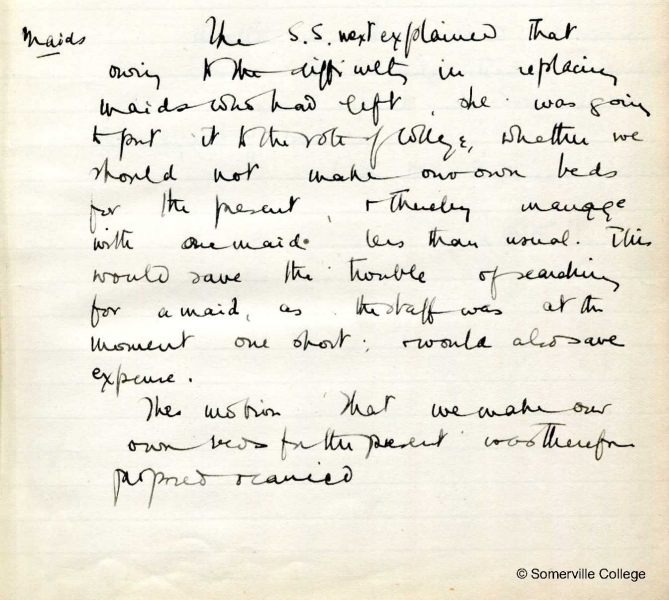

The minutes of the college meeting record the difficulty of replacing maids who had left; the students’ solution was to relieve the pressure on the remaining staff, and save the cost of the wage, by asking junior members to make their own beds. The motion – ‘to make our own beds for the present ‘– was carried.

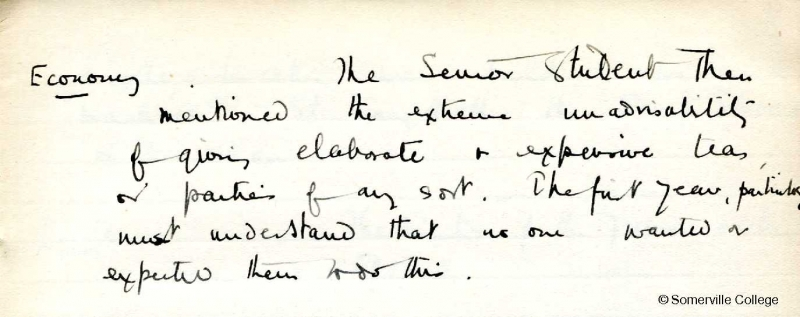

Shortages and the increasing cost of living were also topics under consideration. The Senior Student voiced concern at the ‘extreme inadvisability of giving elaborate and expensive teas or parties of any sort’. The first year appeared to be particularly culpable in this and the Senior Student pointed out that this was neither wanted or expected of them.

At this time, food supplies were increasingly under threat, as merchant ships, carrying imported provisions from the USA and Canada, were subjected to a campaign of attack by German submarines. Britain was growing much more food than it had prior to the war, but by the end of 1917, food would be in such short supply that rationing would be introduced, with sugar one of the first items to be restricted. Not noted for its sophisticated cuisine, the food in Somerville was to deteriorate markedly, with a monotonous reliance on boiled beetroot (at dinner one evening, Swiss student Thilo Bugnion was heard above the hubbub, enquiring ‘What ees this bloodee stuff?’). Hot, non-alcoholic beverages and tea-time treats were not only the bedrock of student socialising but were a vital supplement to the college food provision. Such tea parties would be sorely missed.