Among the many varieties of war work undertaken by Somervillians, a small number of former students chose to join the Women Patrols organised by the NUWW (National Union of Women Workers). Janet Gulliver was one; she had come up to Somerville in 1907, at the age of 20, to read mathematics and had started her career as a teacher in 1911. By February 1916, she was a volunteer with the Swansea ‘Woman Patrol’.

These patrols were one of two types of prototype police force, emerging early on in the war, staffed by women. At the start of the conflict, huge numbers of young women had been affected by ‘khaki fever’ and there was widespread concern that war-time conditions could lead to a decline in morality and undermine society. Older, middle-class women responded by organising volunteers to monitor the behaviour of young women fraternising with young men in public places.

The patrols’ volunteers included suffragists whilst the other force, the Women’s Police Service (WPS) was founded by suffragettes. The NUWW saw the role of the patrols as providing a ‘steadying influence’. The volunteers patrolled towns and cities, acting as a deterrent to immorality; they had no powers of arrest but could give evidence in court. To the volunteers, these patrols provided opportunities for women to combine patriotic and moral duties and to further the cause of feminism, as both the Women Patrols and the WPS demonstrated what women could do as part of a professional police force. Khaki fever diminished as the war lasted beyond its anticipated duration and there were more war-time roles available to women, but concerns over public morality continued, as did the patrols.

Other Somervillians who volunteered included English teacher Alice Stainer, a member of the Women’s Patrol in Nottingham, Eveline Edmonds who lived in Putney, and Anita Miles, a part-time volunteer with the Cheltenham patrol. Theodora Powell was a member of the Godalming Women’s Patrol, an area with a massive Canadian military presence as huge army camps were established on the commons nearby to accommodate thousands of troops. Janet Gulliver, at 28, was younger than her fellow Somervillian volunteers but was probably still considerably older than many of the women and girls she would have policed in Swansea.

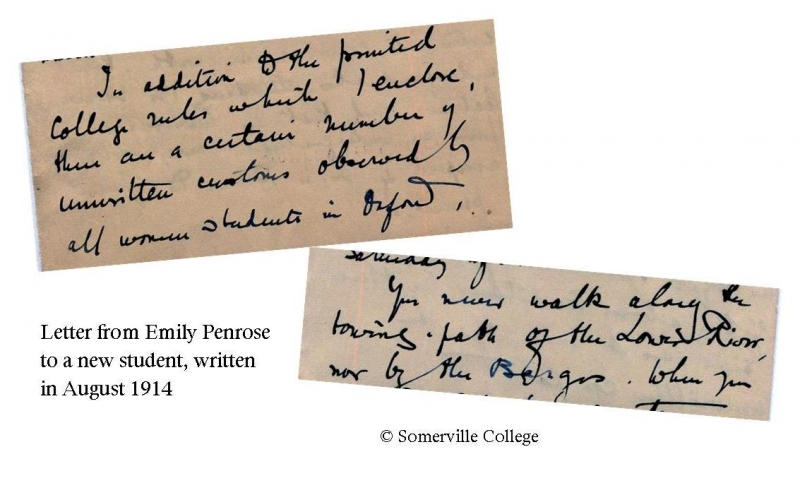

Reports by Women Patrols working in Oxford noted that Carfax, George Street and Cornmarket were popular meeting places for young men and girls, their conduct attributed to foolishness as well as immorality. Indecent behaviour and ‘actual immorality’ were recorded as taking place near the canal; Somerville students had long been forbidden from walking along the towpaths, suggesting that the area’s dubious reputation predated the outbreak of the war.

As hoped, the potential of women officers in the police force was recognised and when the war ended, the Metropolitan police developed its own women’s police service, recruiting the first supervisor from the NUWW, whilst the WPS, with its suffragette associations, was disbanded.