Past exhibition

Loggia Exhibition May 2022

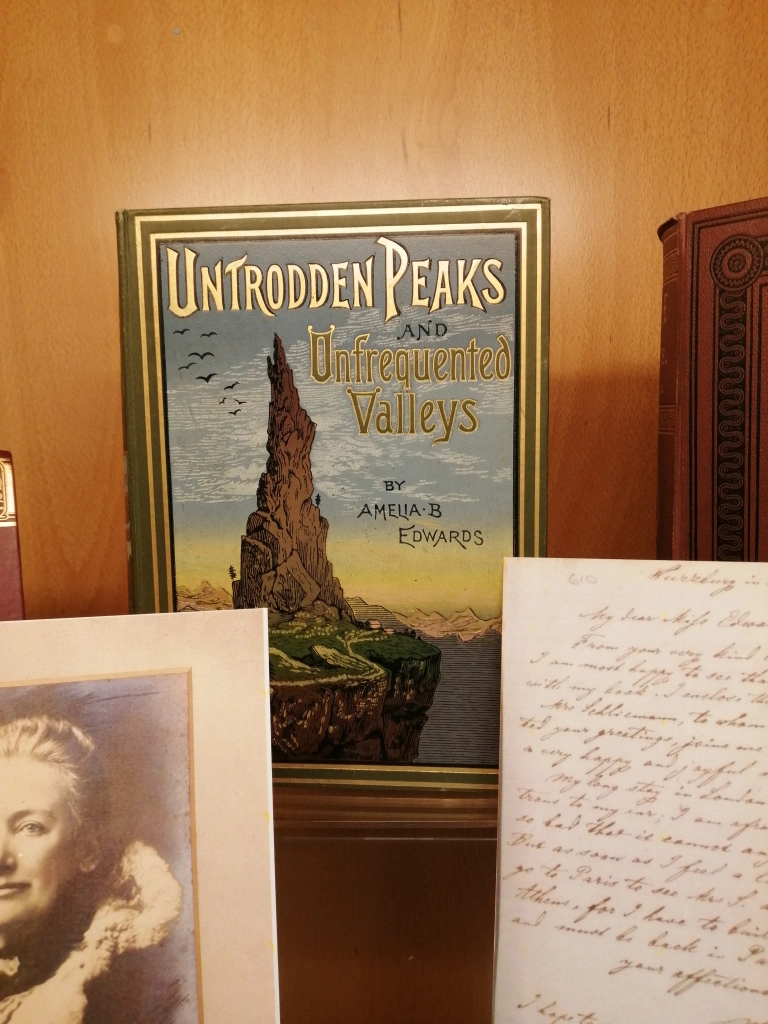

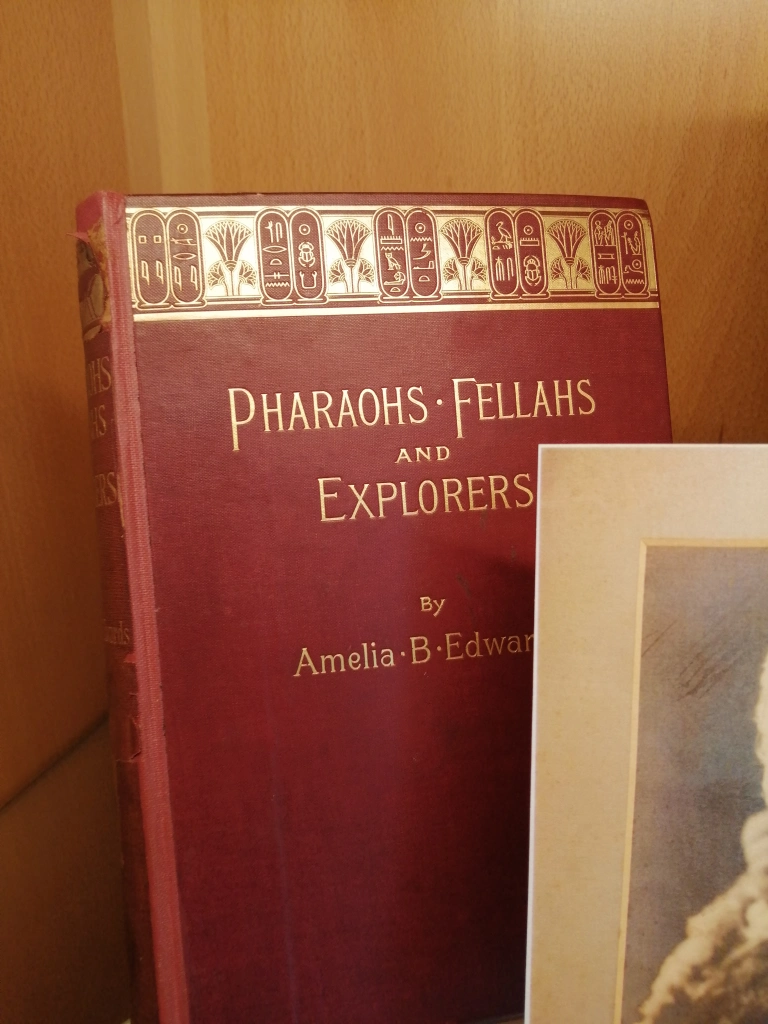

Amelia B. Edwards (1831-1892)

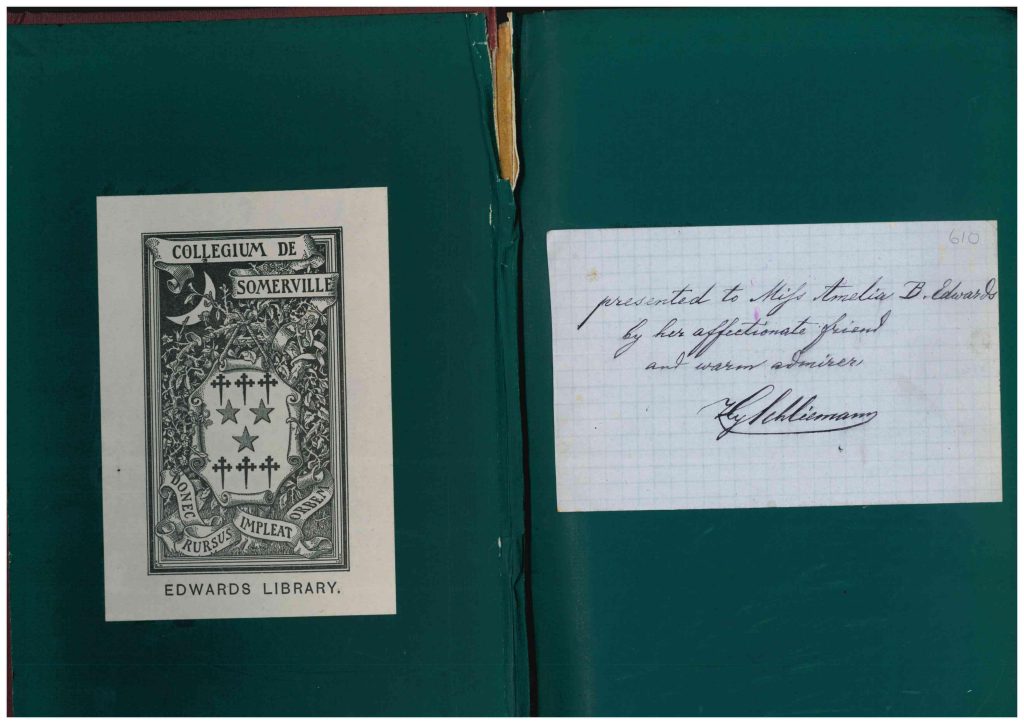

Bequest to Somerville

Somerville has been fortunate to receive a number of generous gifts and bequests: one of the earliest and largest was that of the books, watercolours, papers and some of the antiquities of writer, Egyptologist and artist Amelia Edwards.

These books formed part of the early library collection, having had a room especially constructed for them at the East end of the newly opened (1904) Library building. Edwards gave us her books to benefit, and make the lot easier of, subsequent generations of women striving to get equal educational opportunities, it is presumed because she was an acquaintance of the College’s first two Principals, Madeleine Shaw Lefevre and Agnes Maitland (whom she would have known through their involvement in the Egypt Exploration Fund, as it was then known).

As the 1907 SSA Report states, “It is the library of a person interested in many subjects, who read everything that came her way and made the utmost of the comparatively limited opportunities of a woman in the mid-Victorian era.”

Early writing

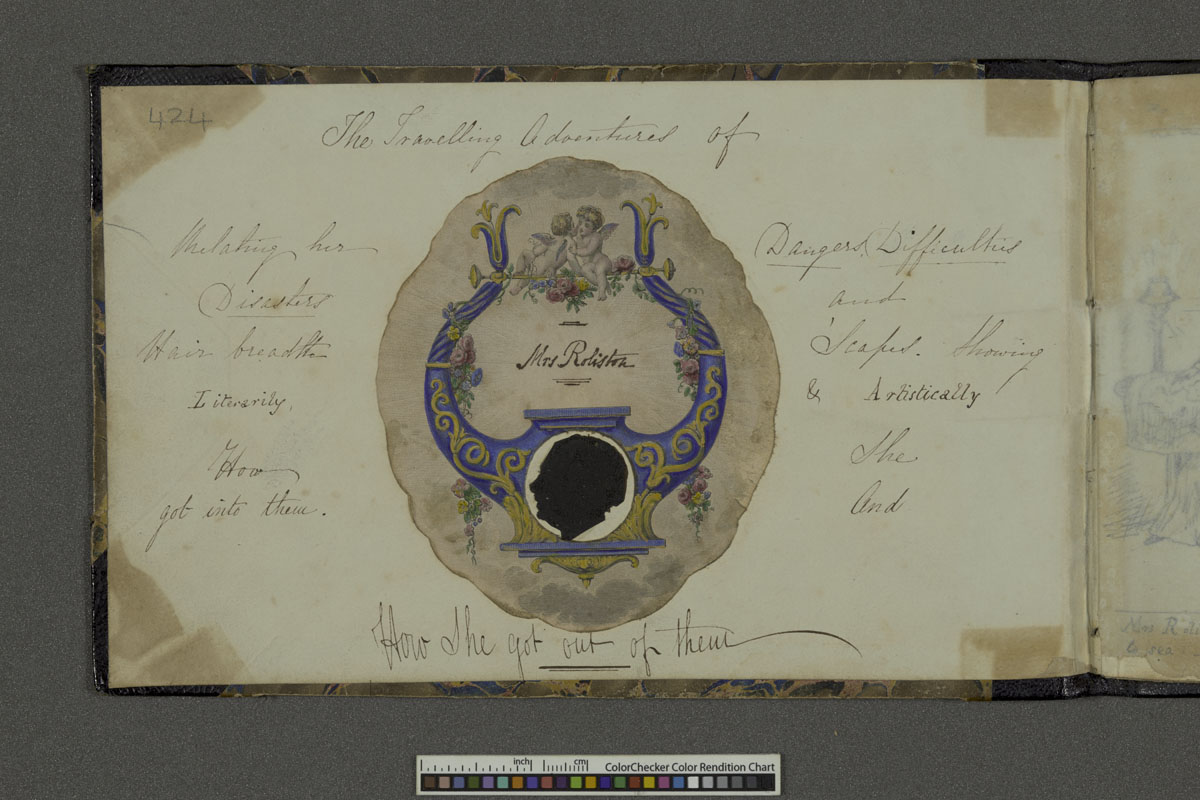

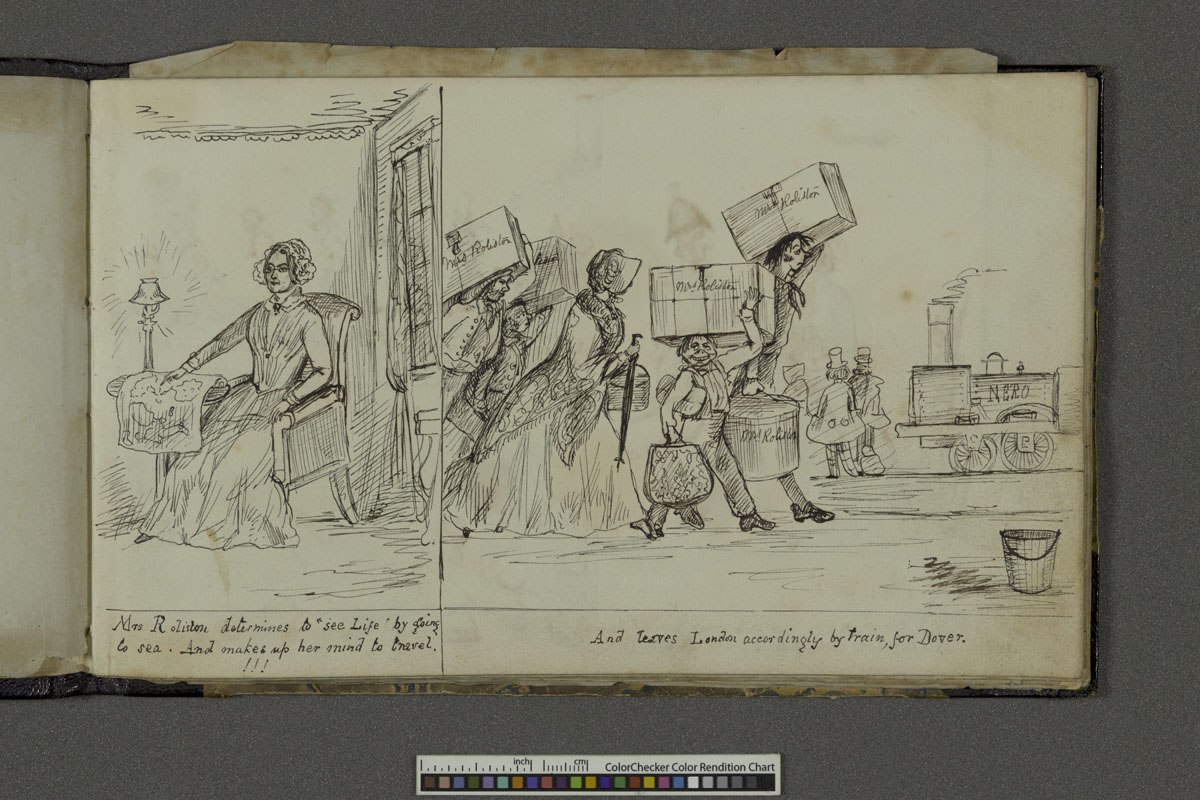

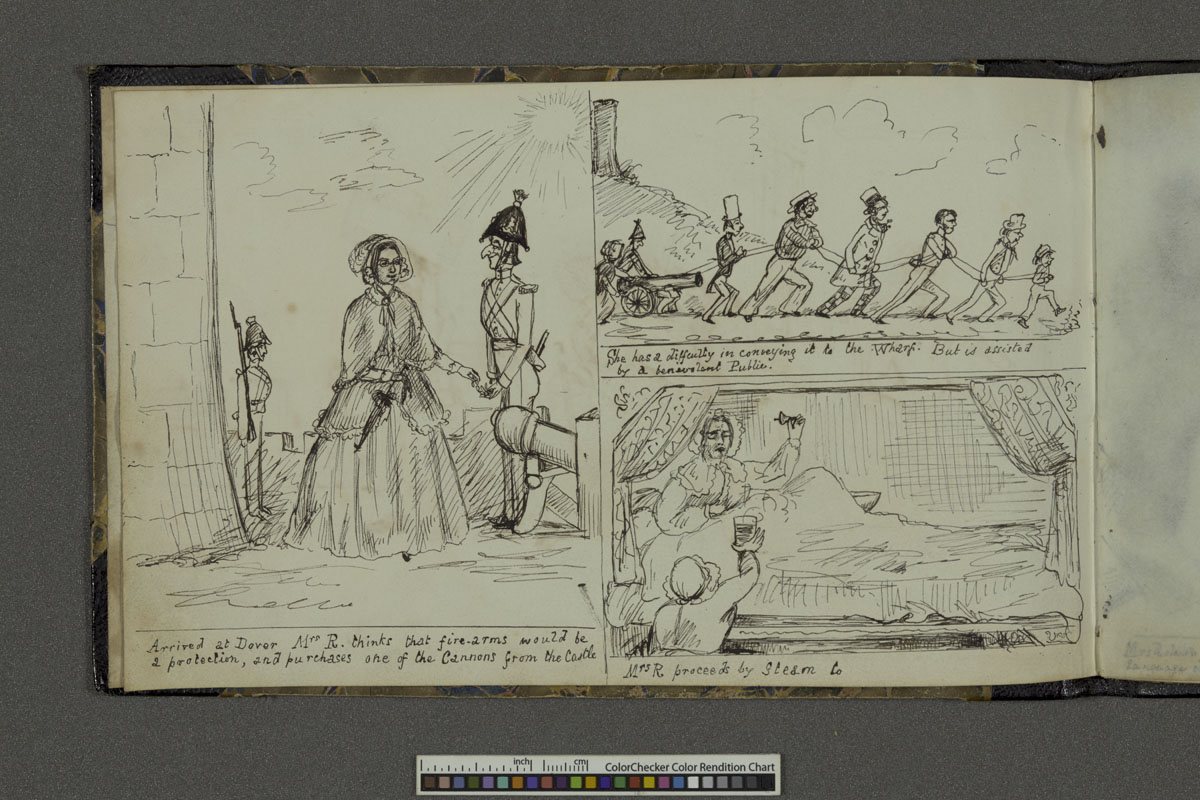

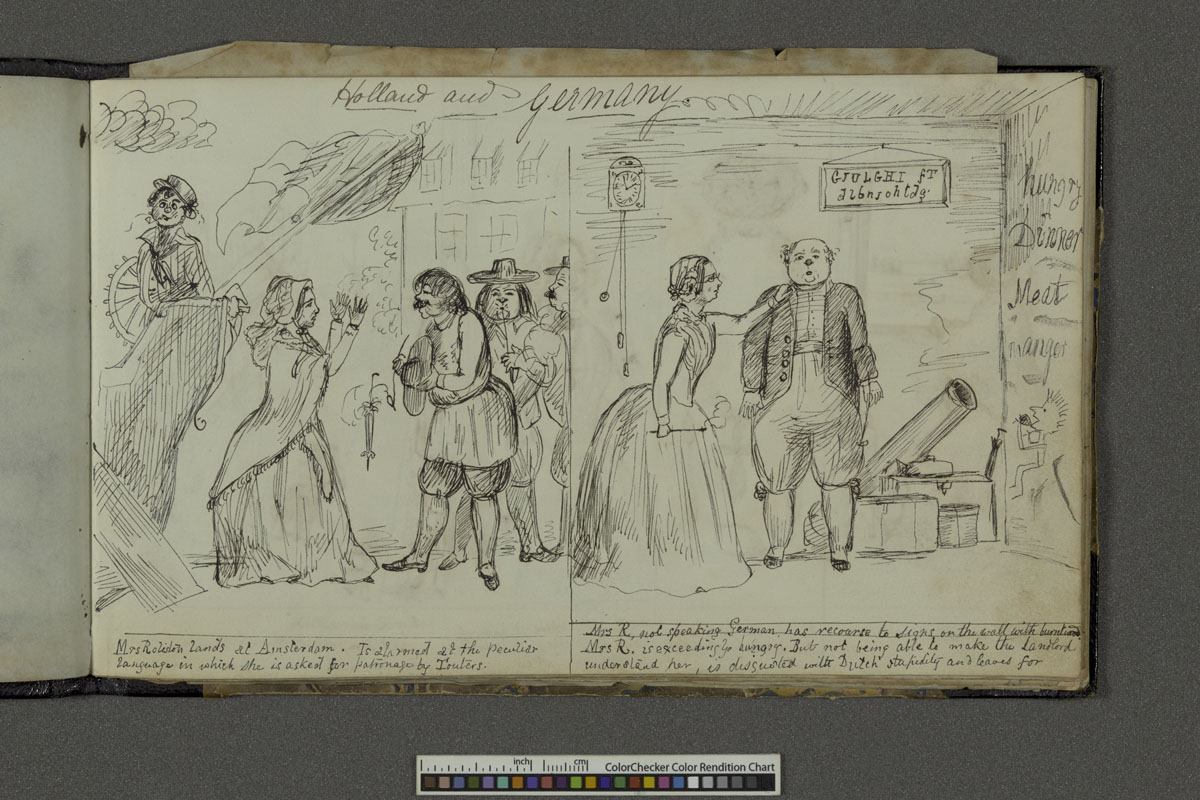

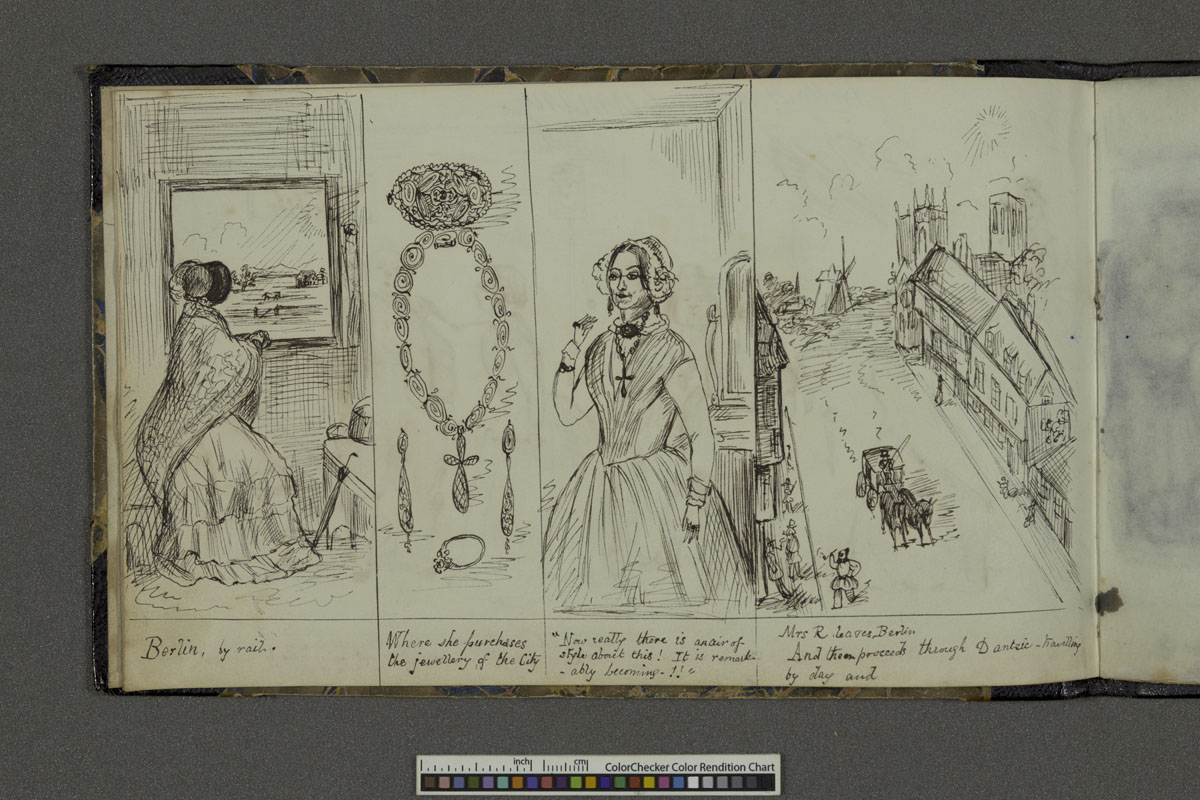

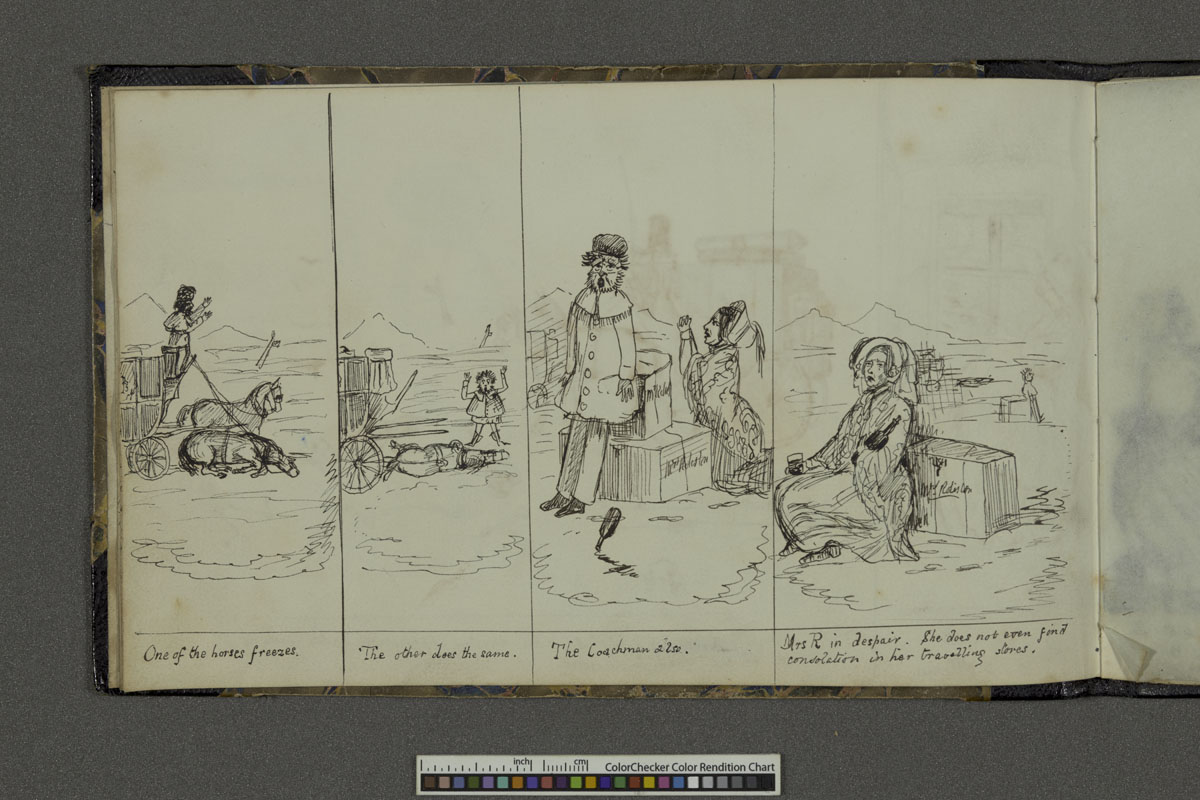

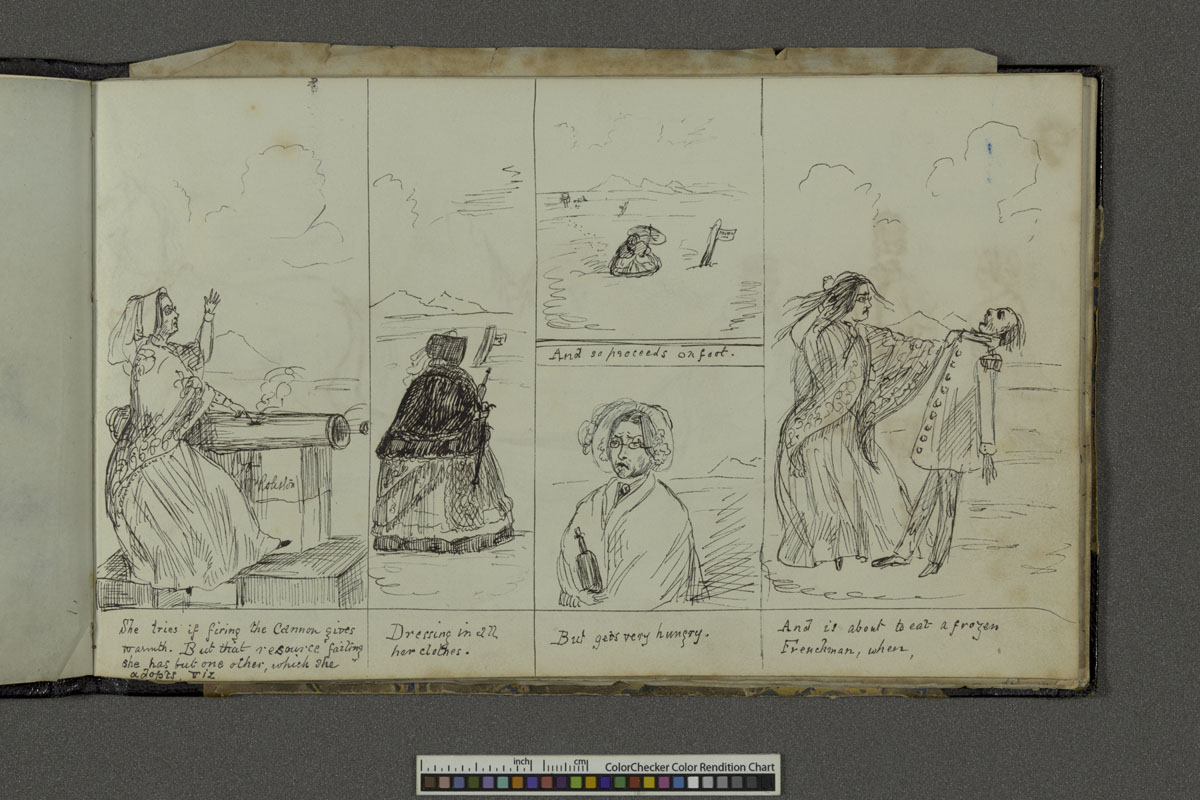

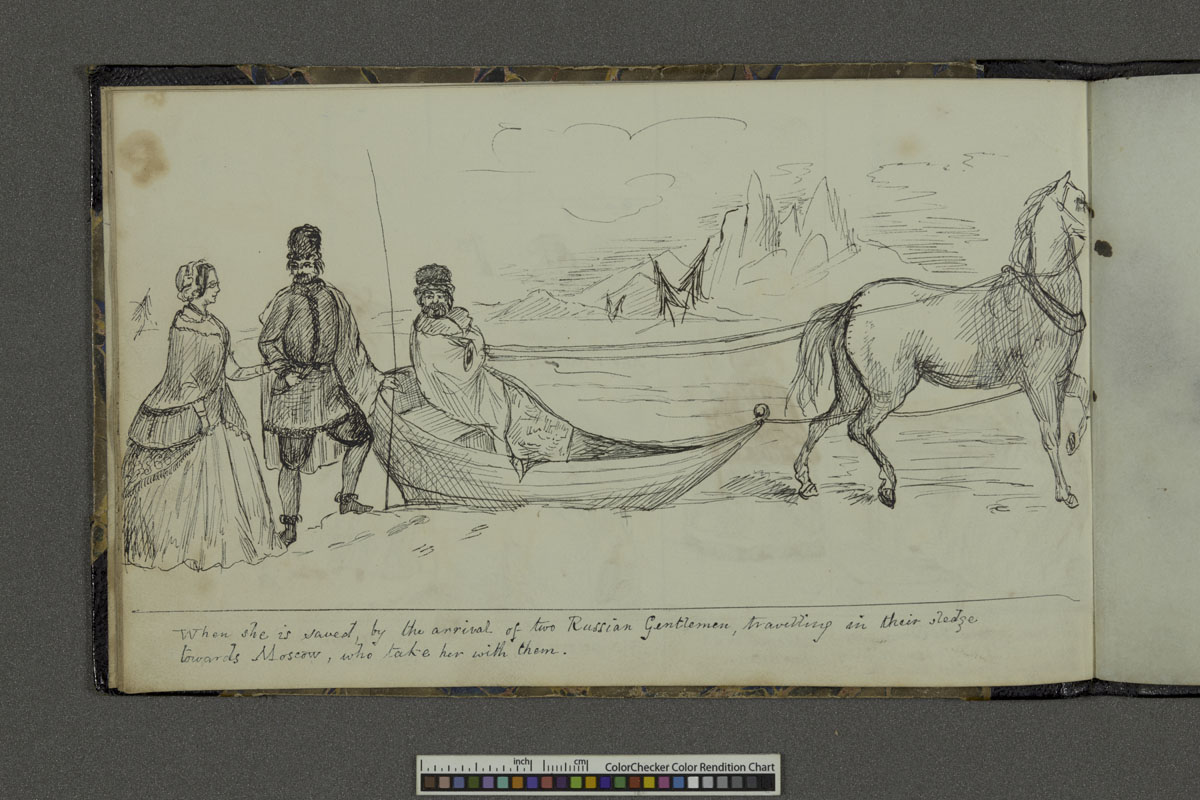

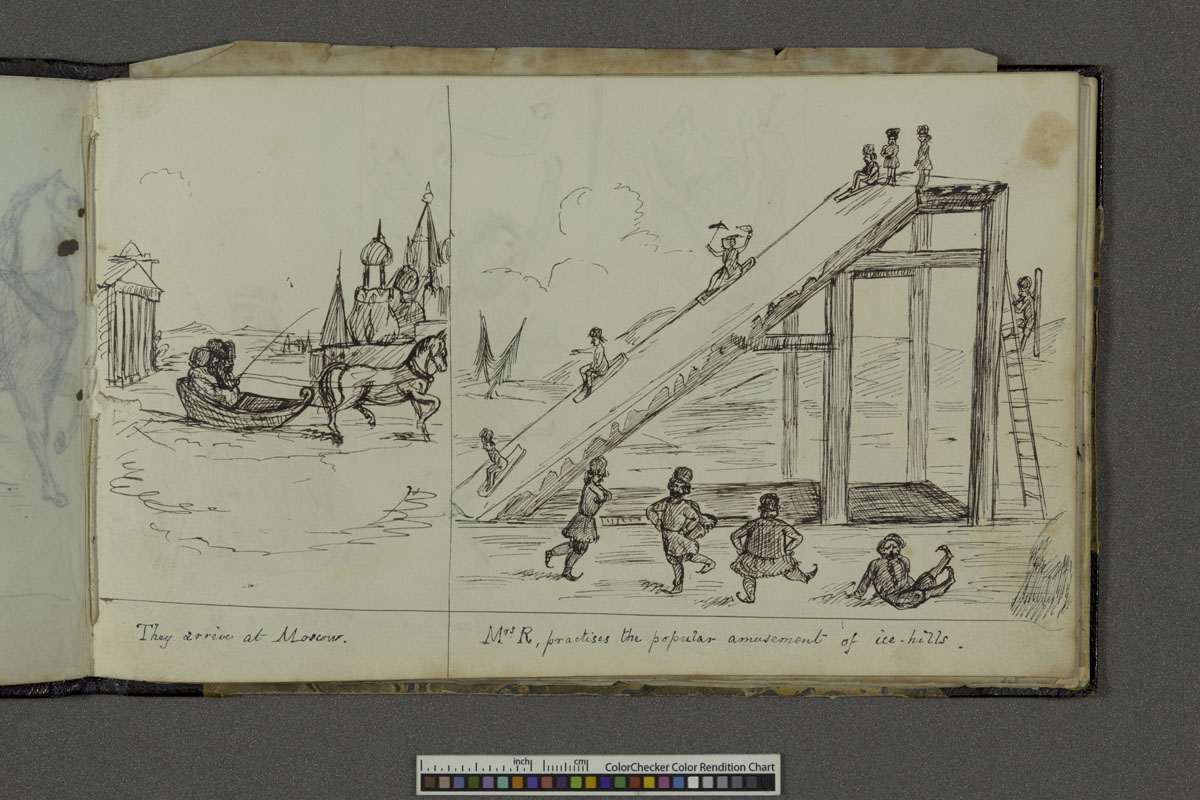

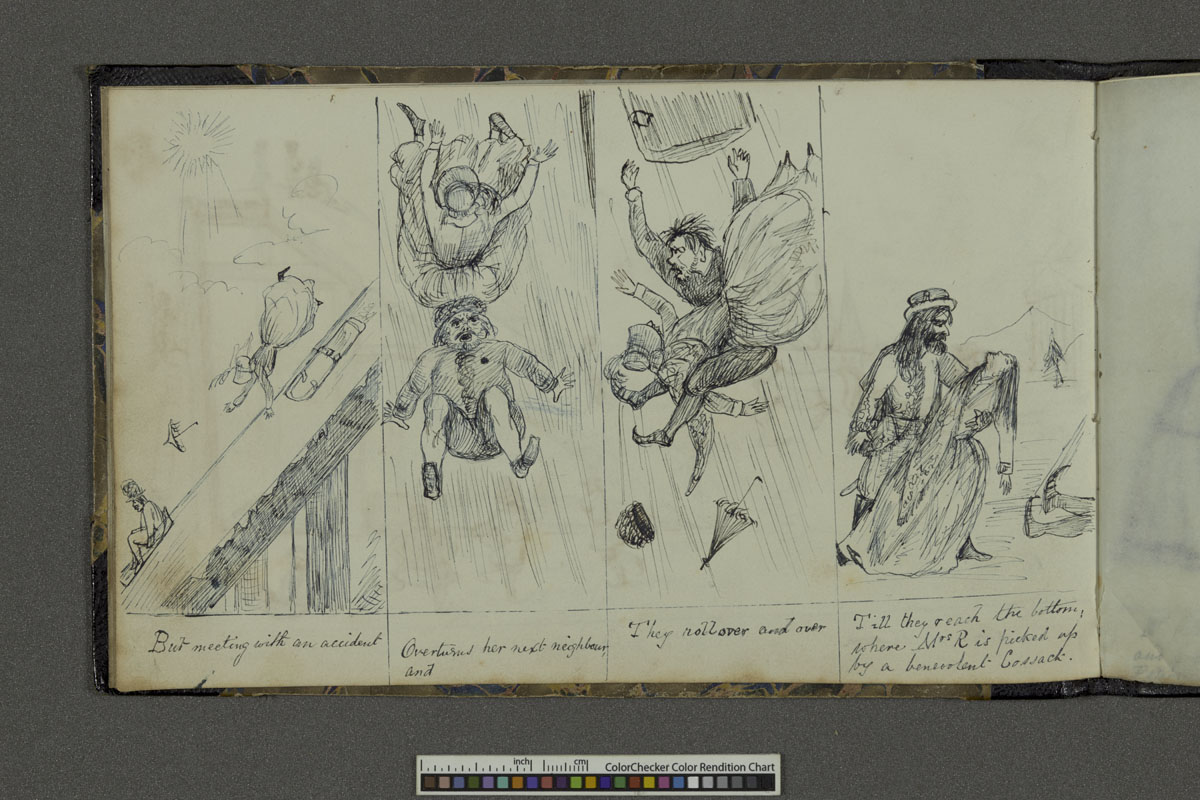

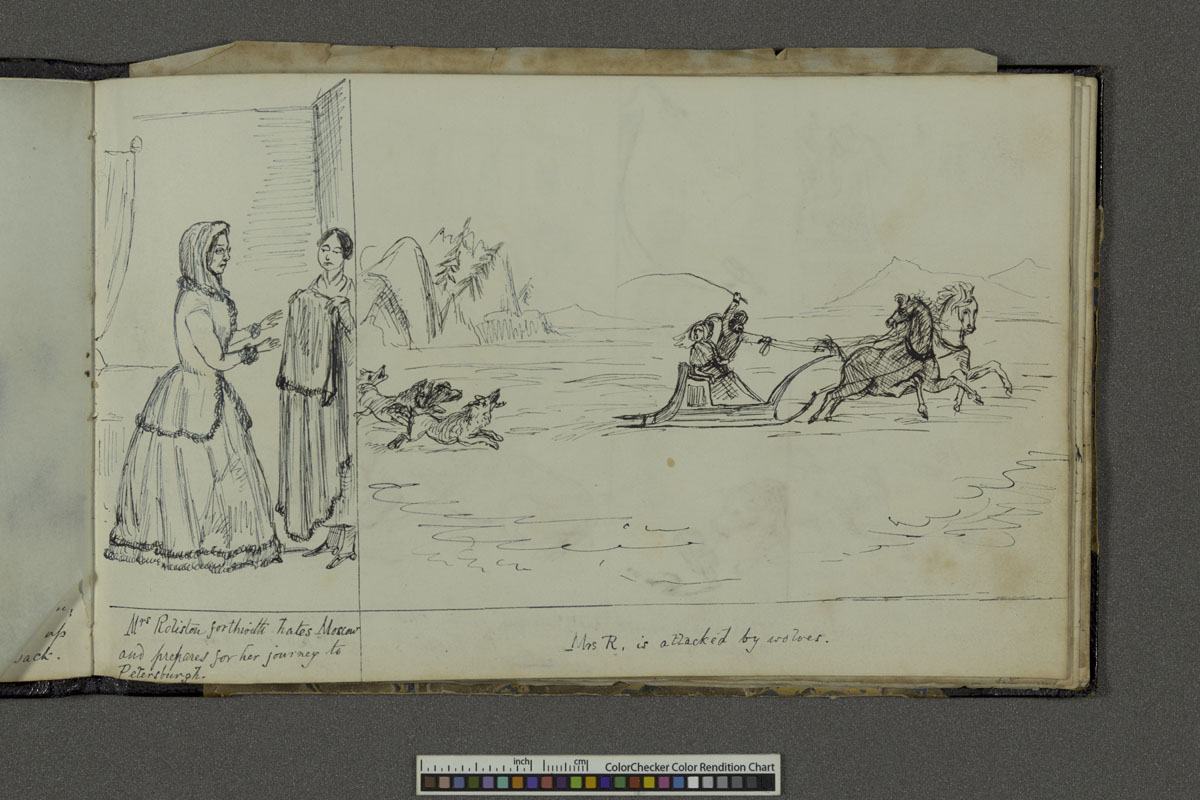

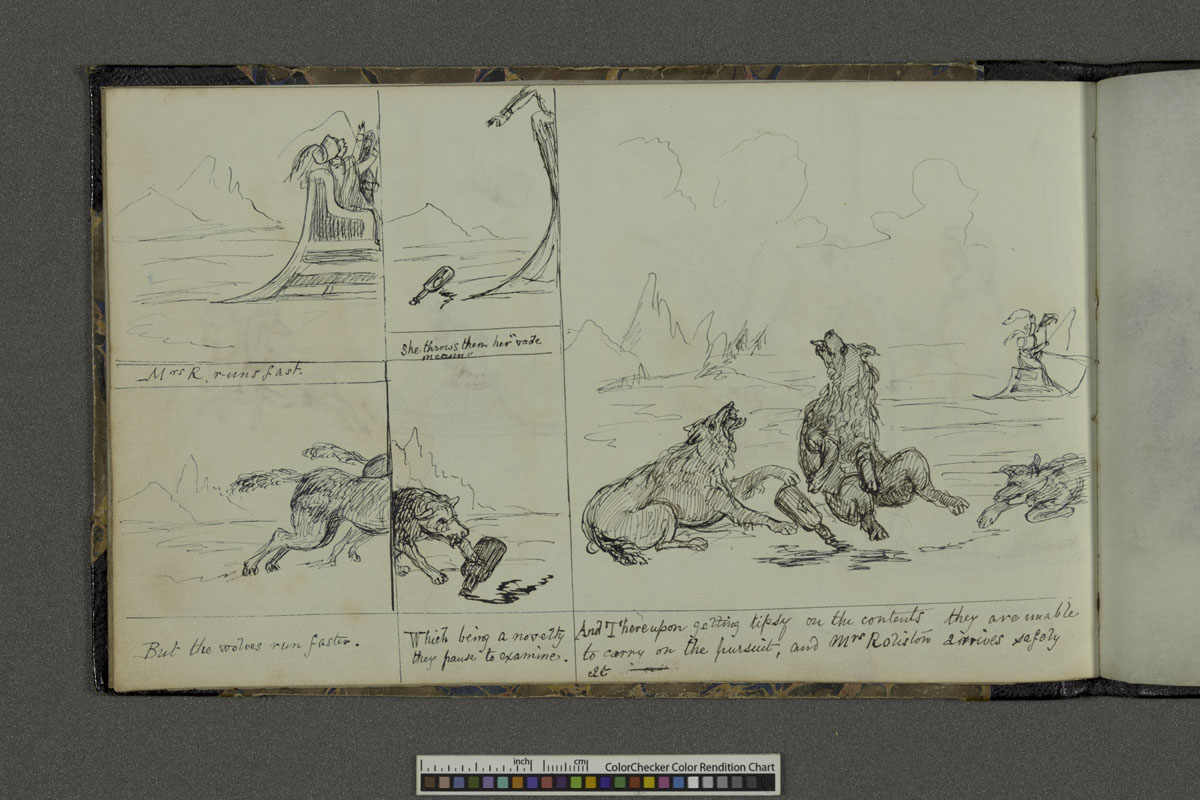

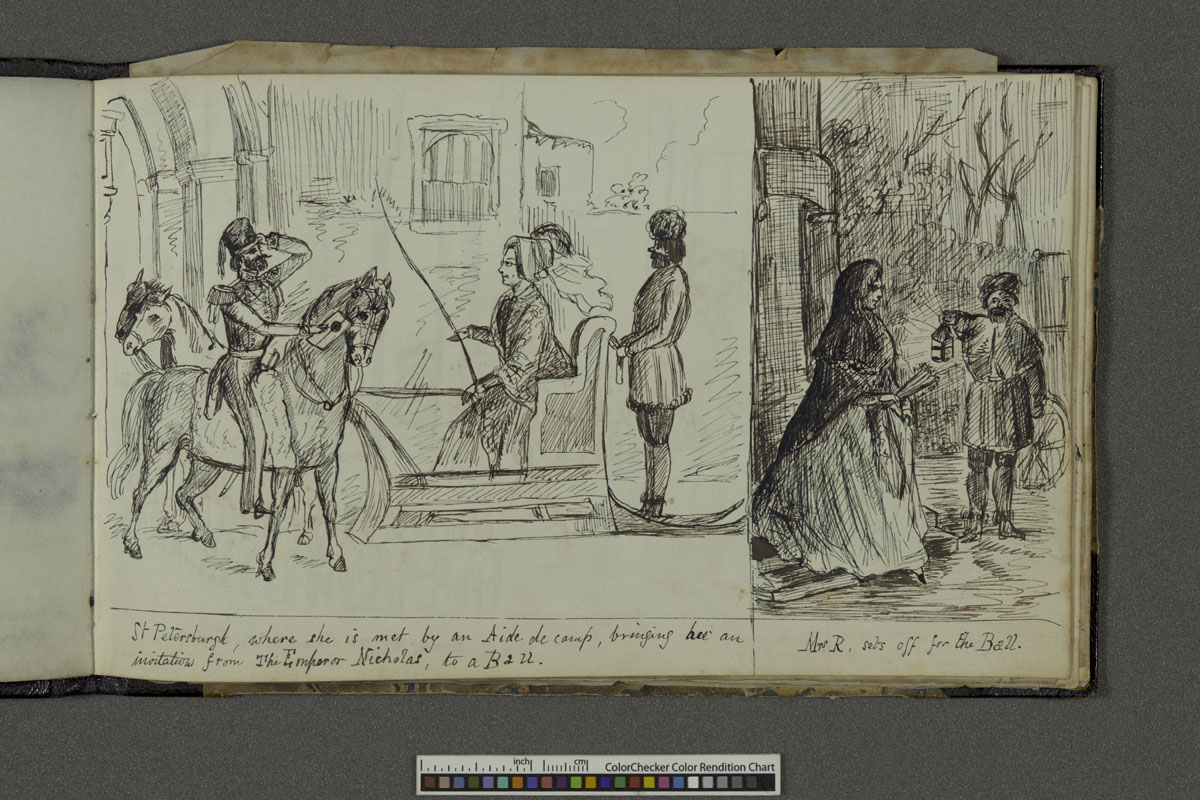

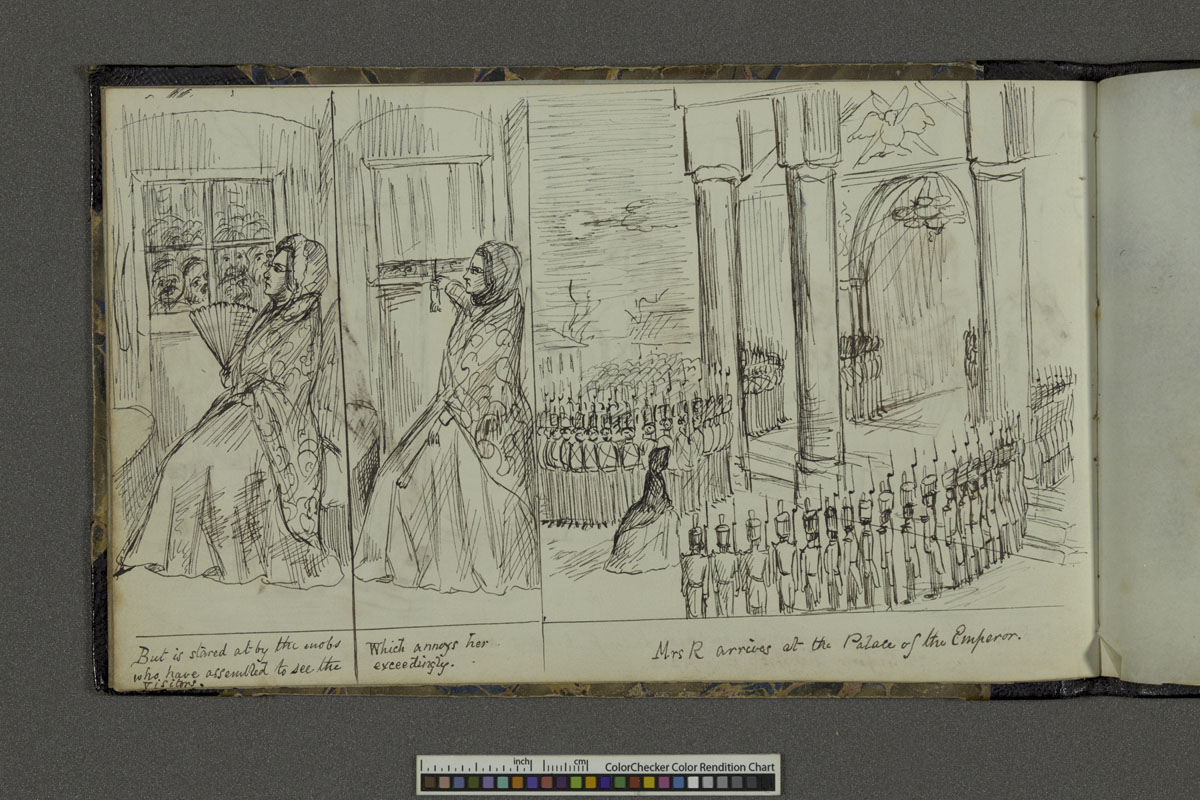

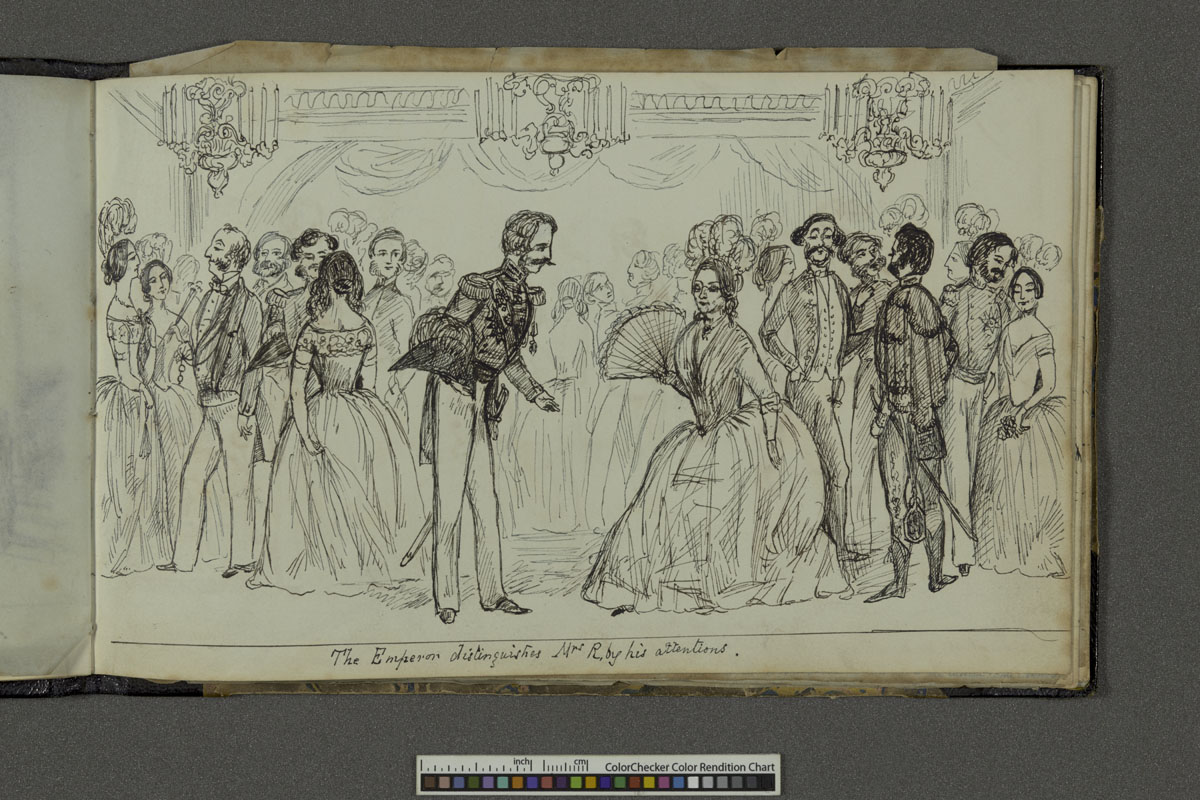

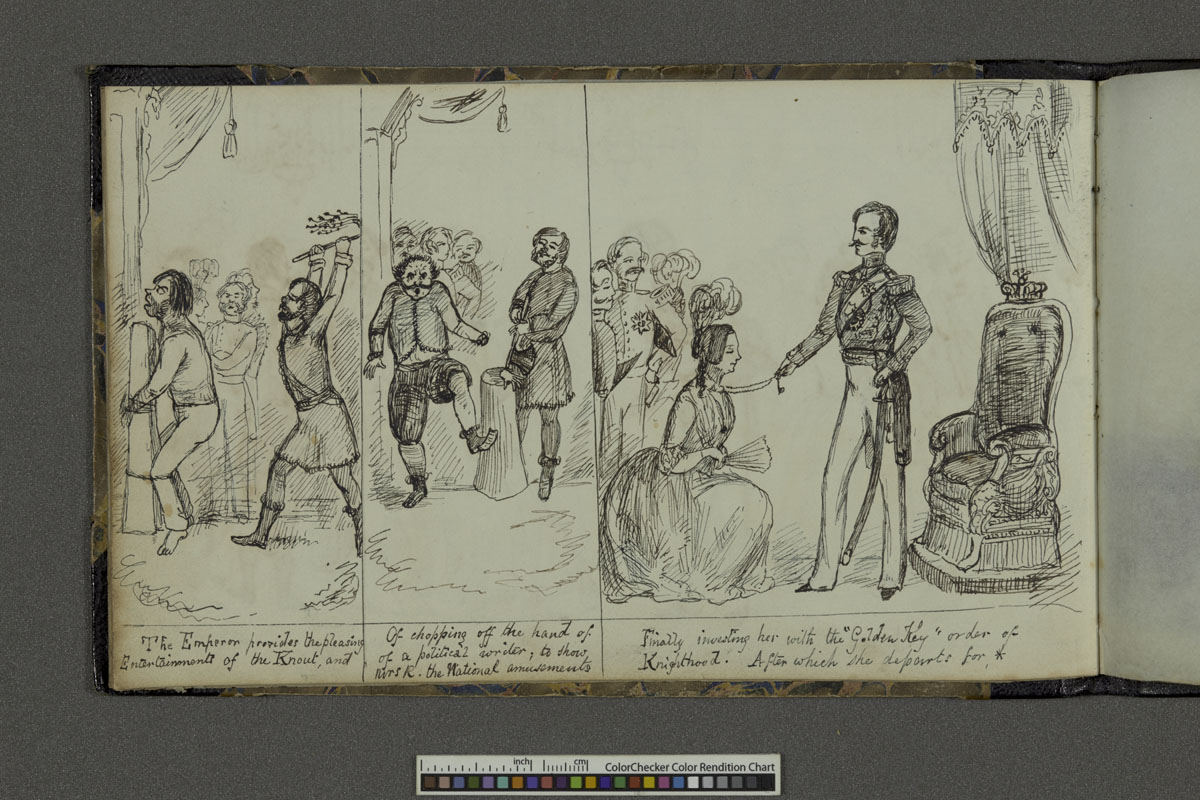

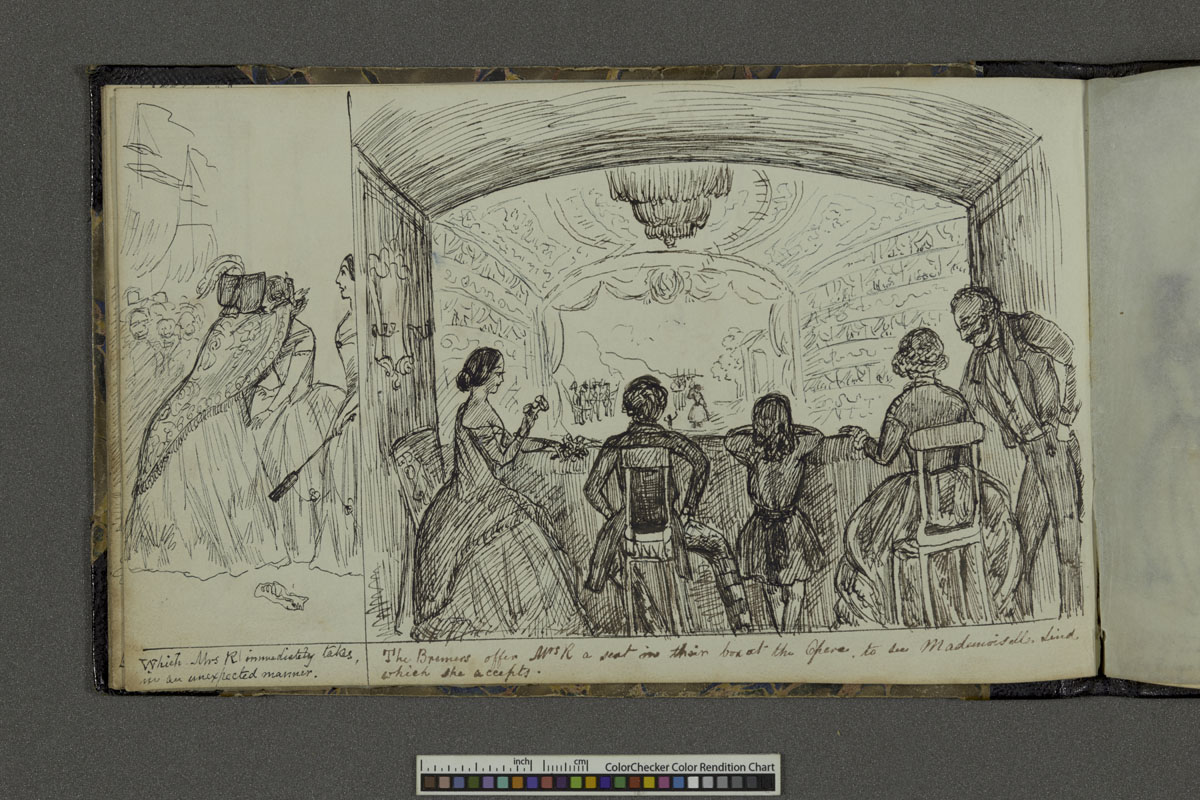

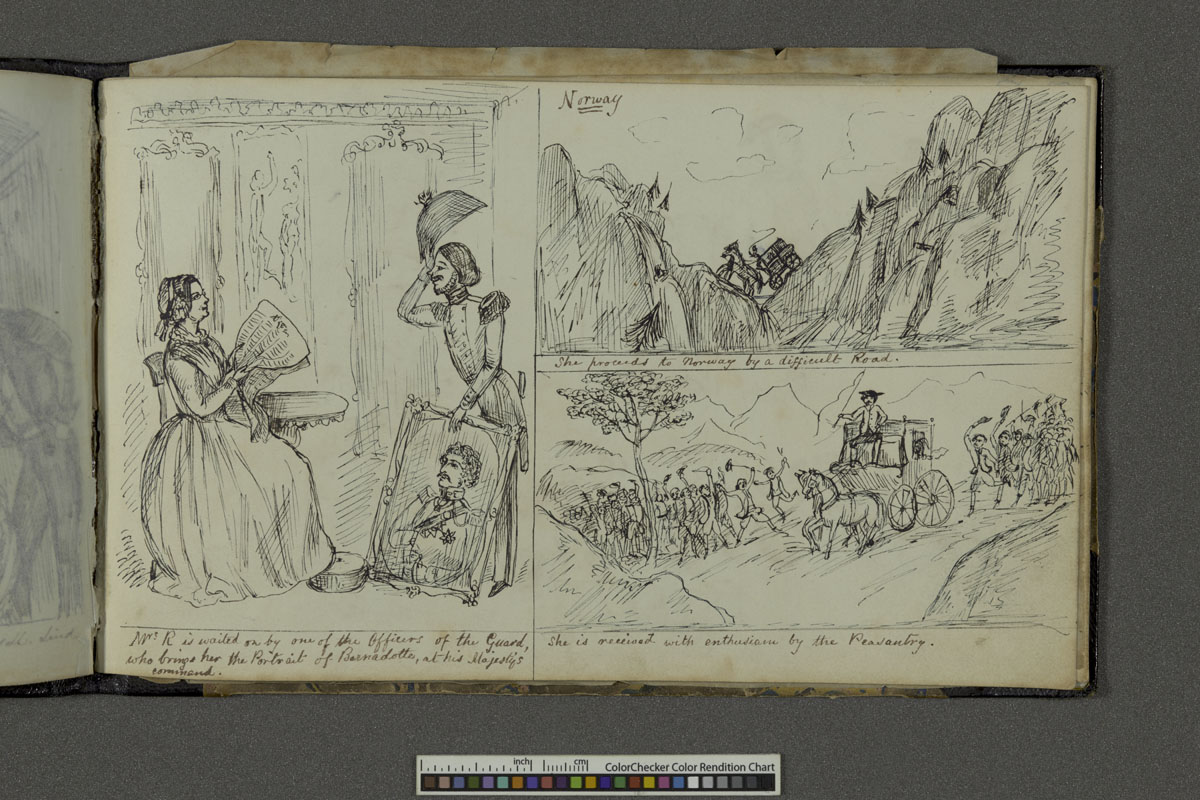

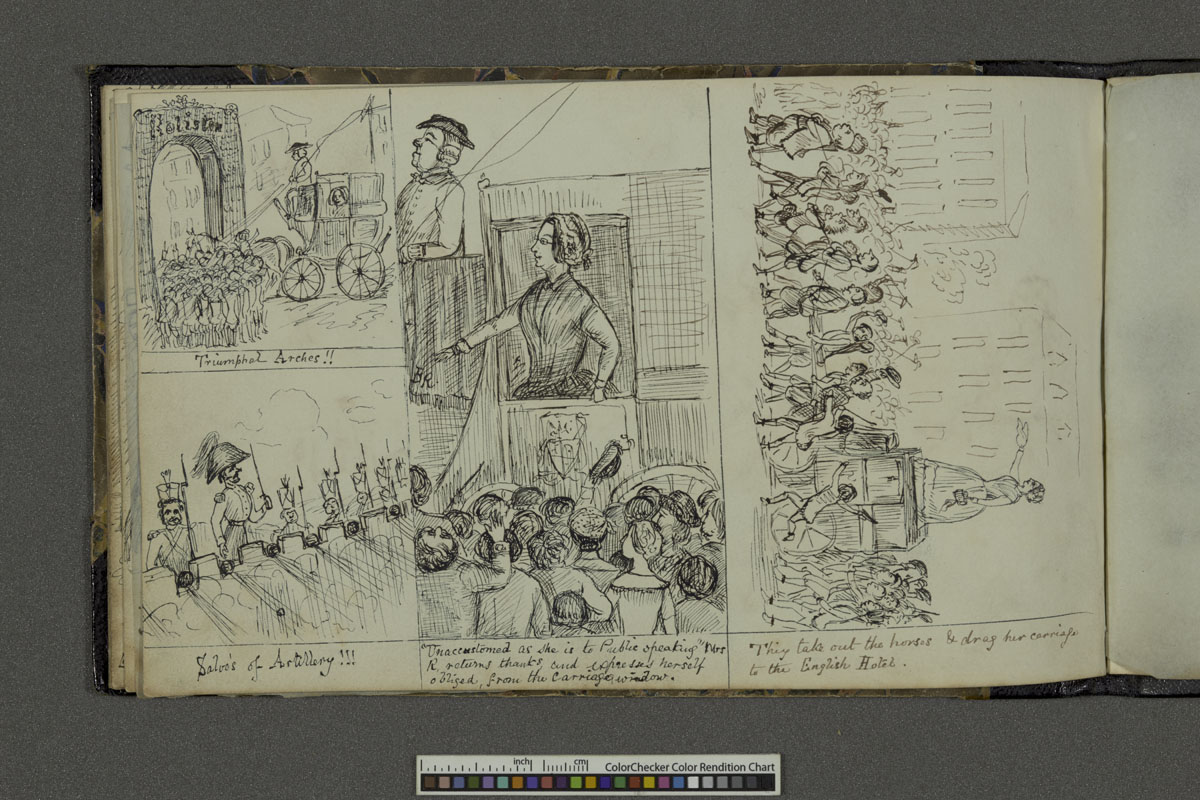

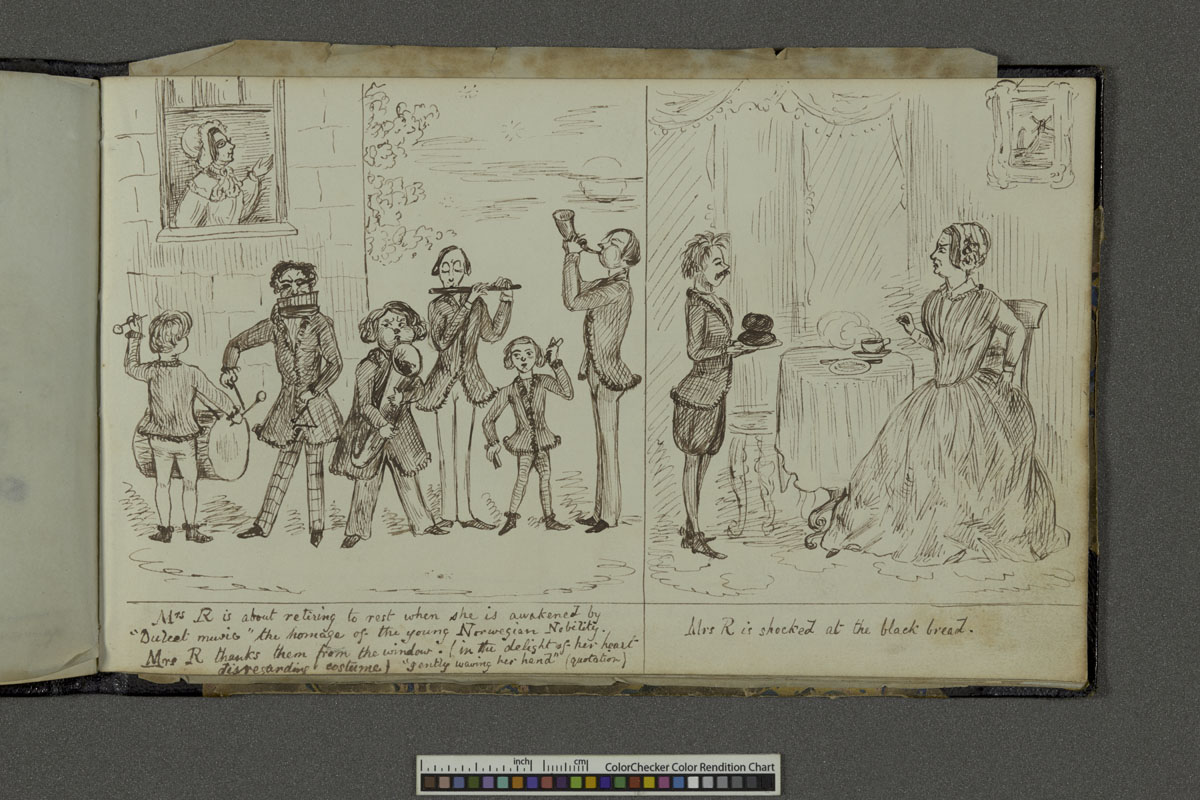

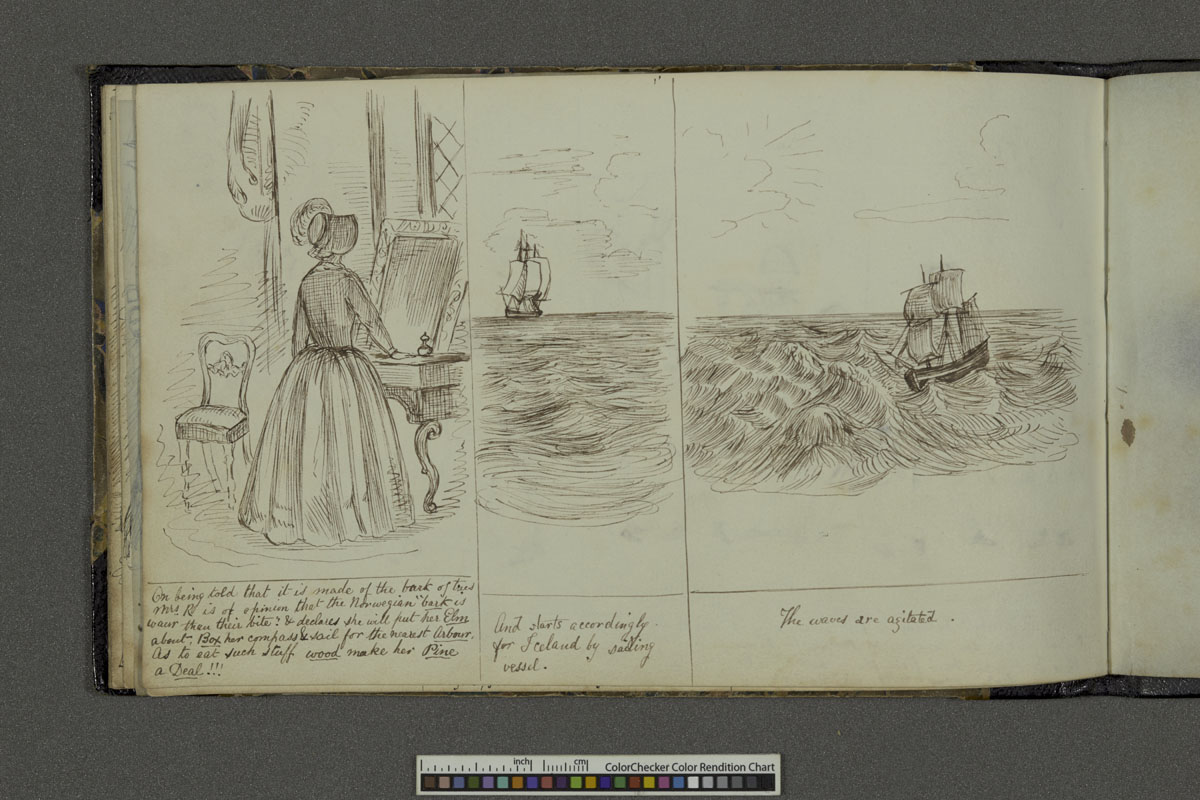

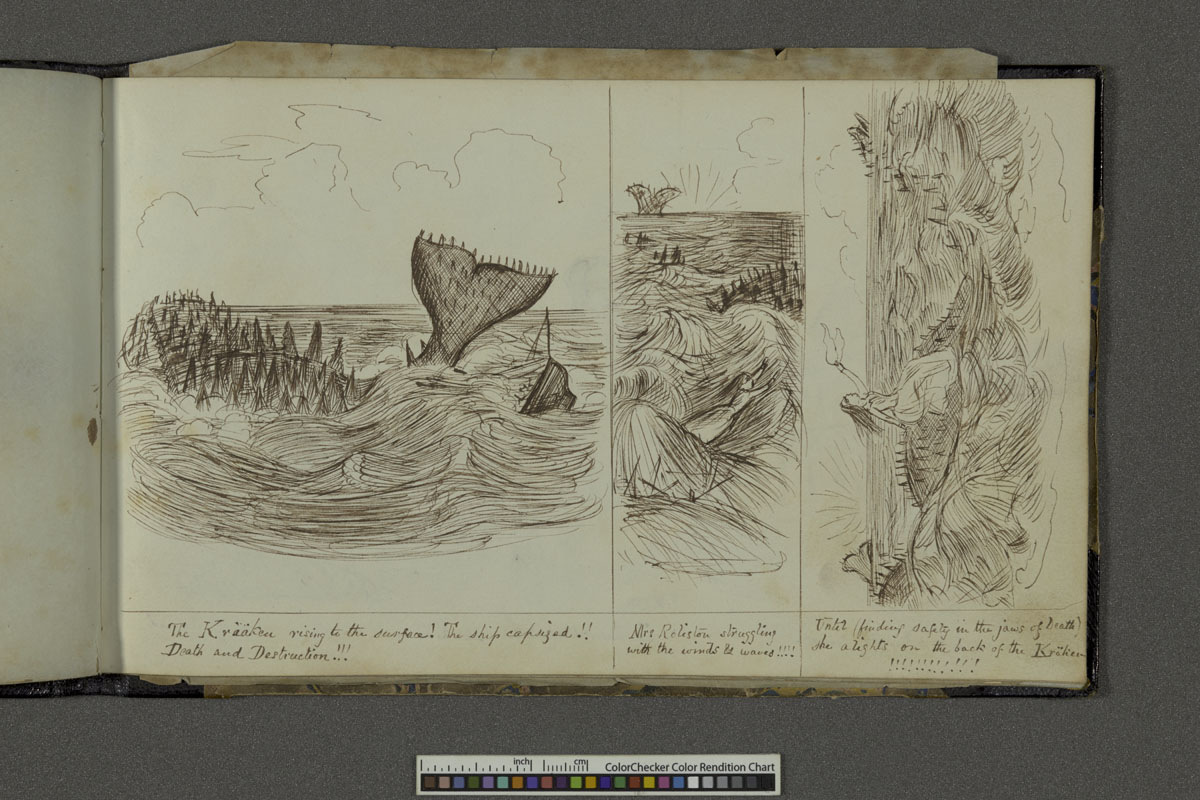

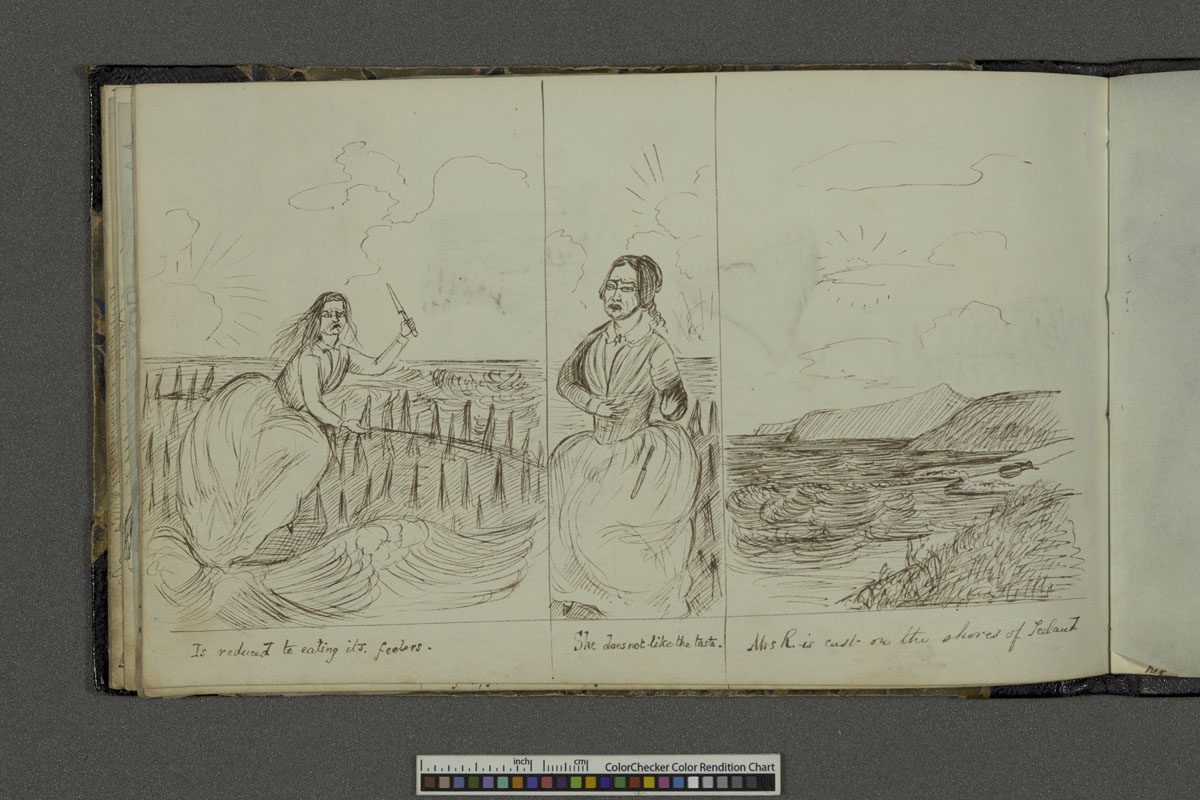

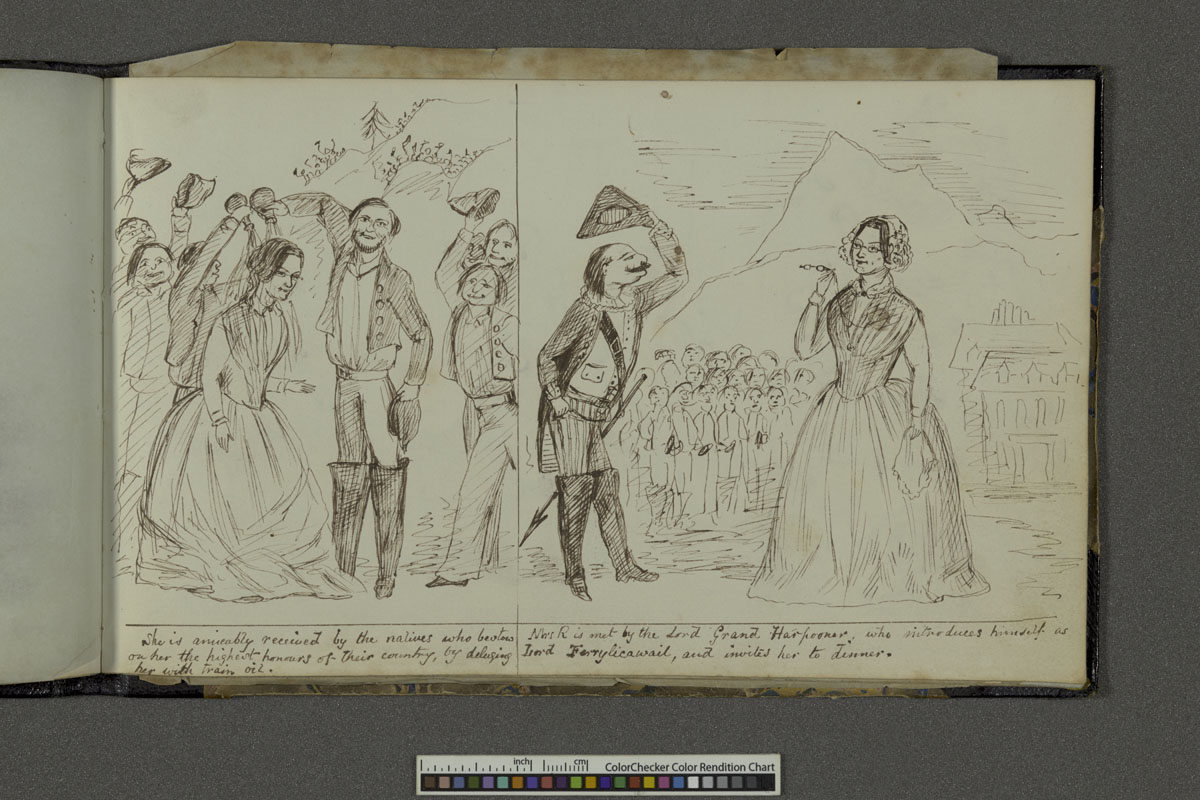

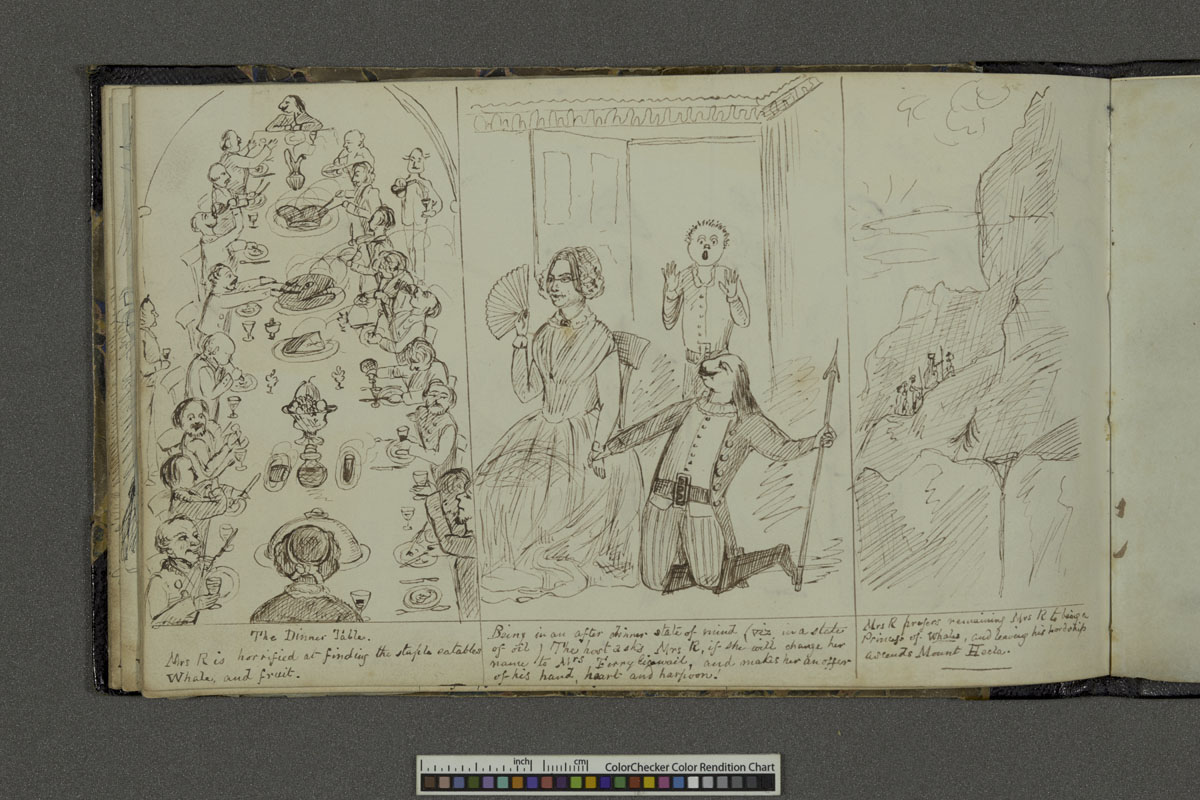

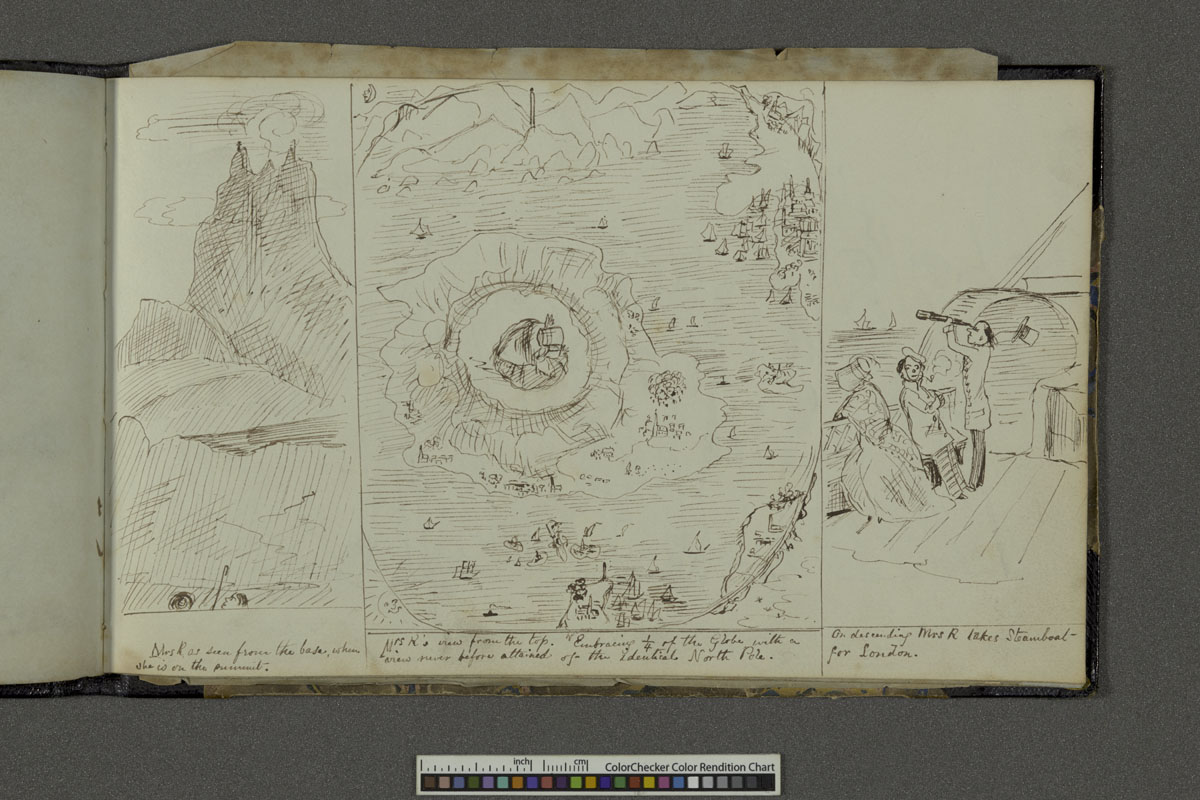

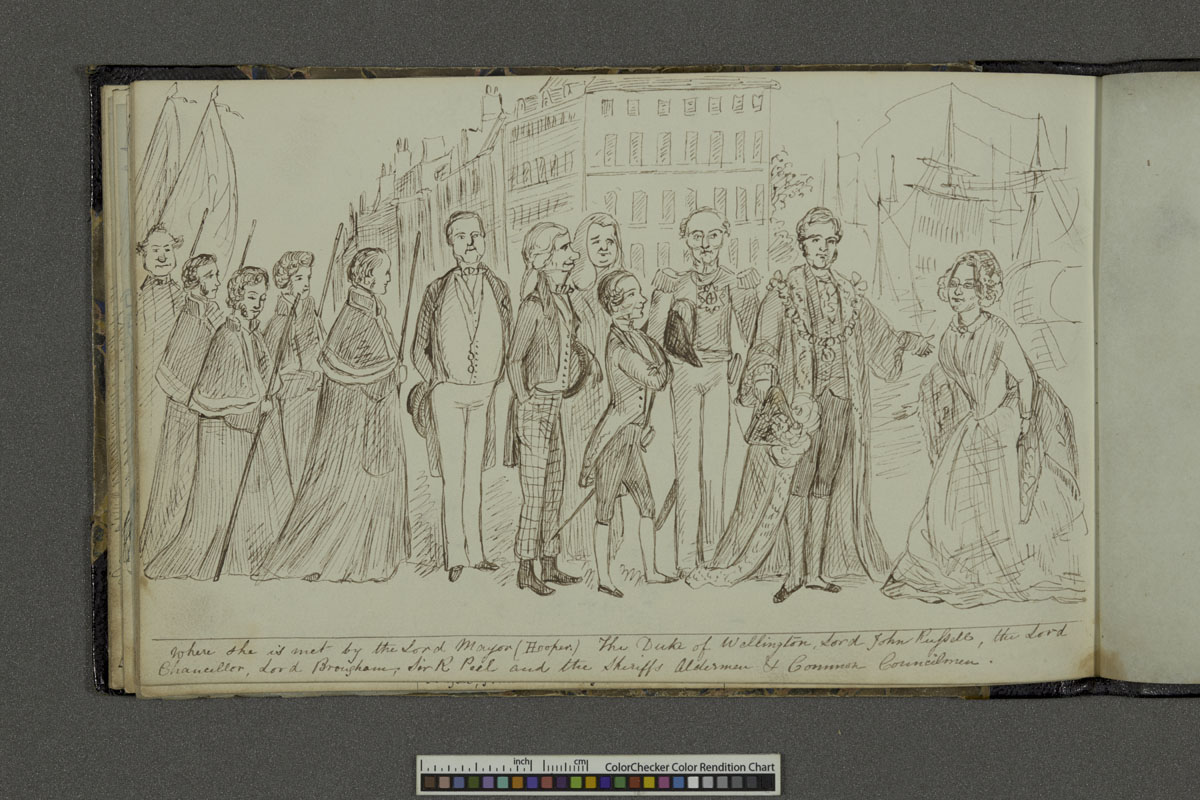

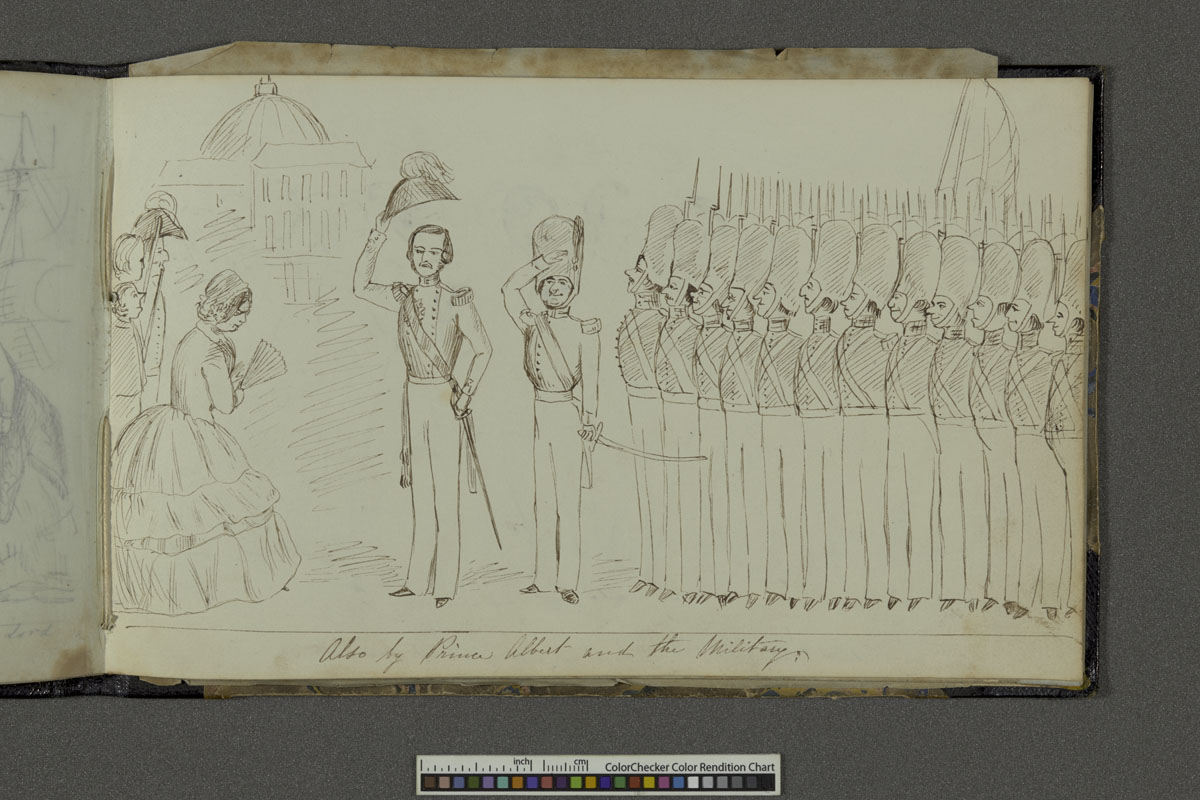

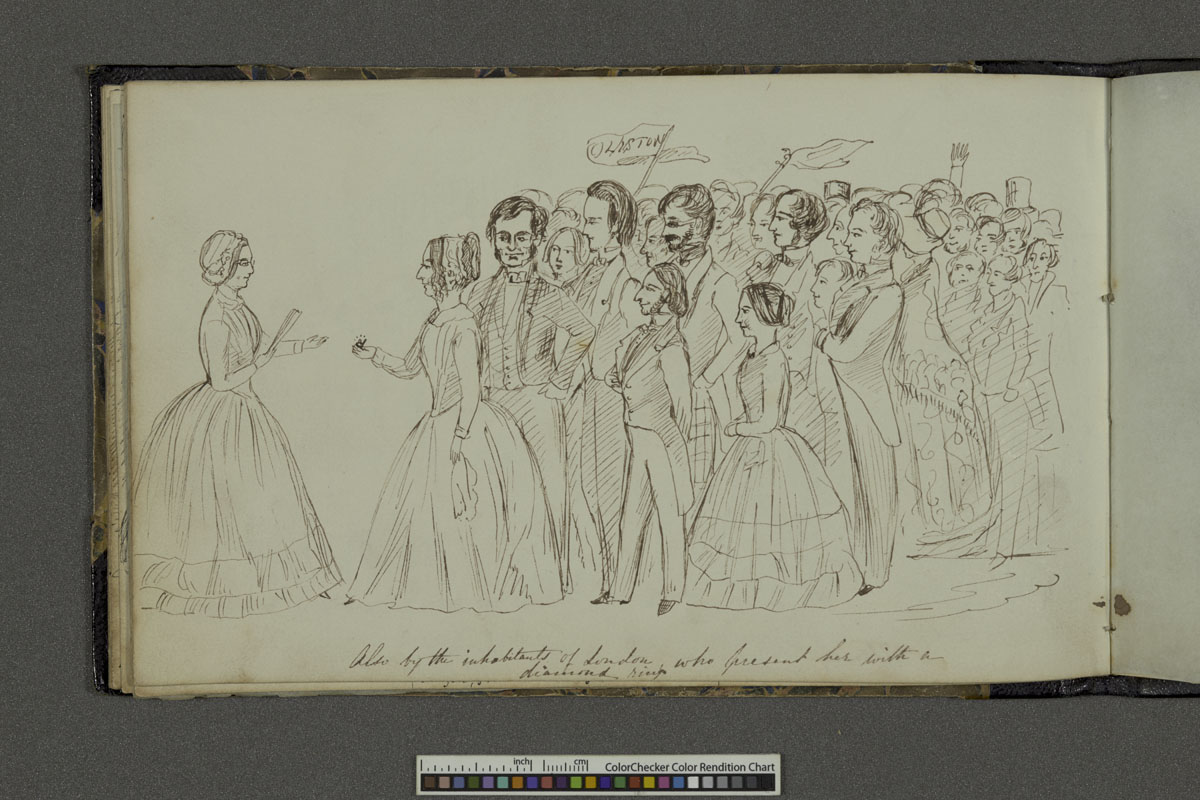

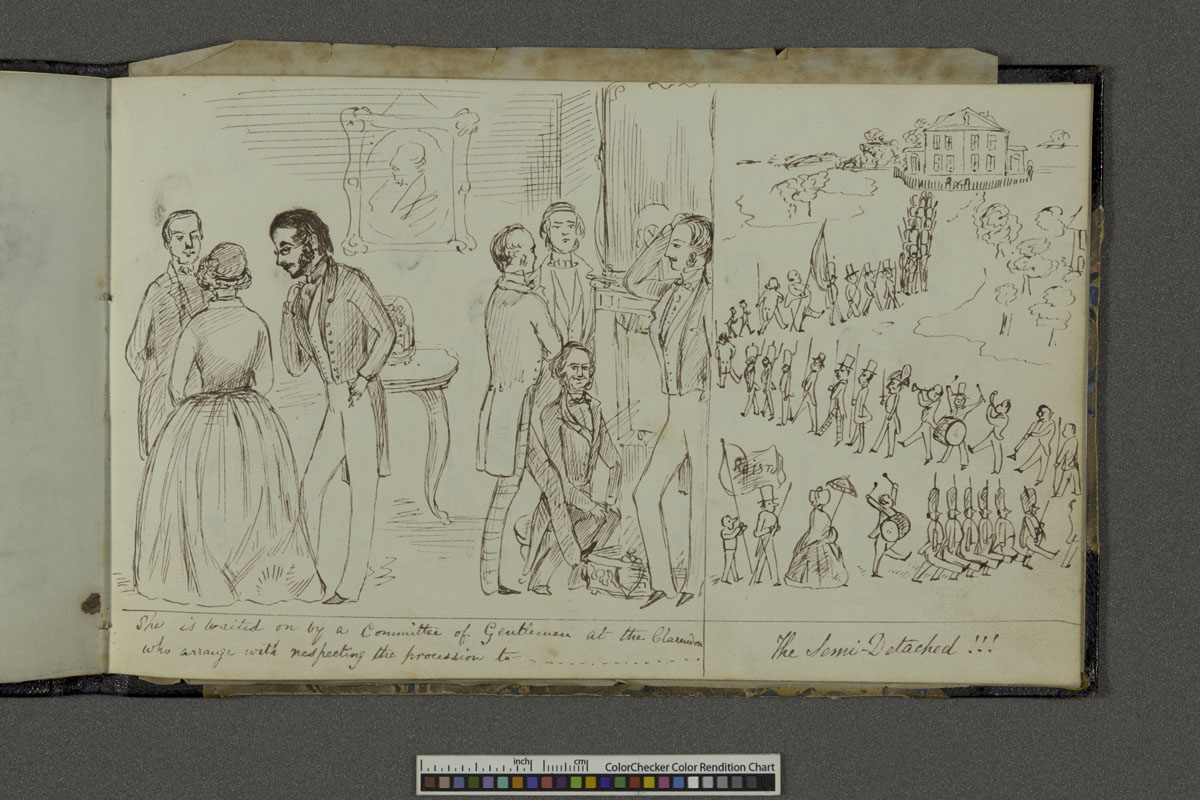

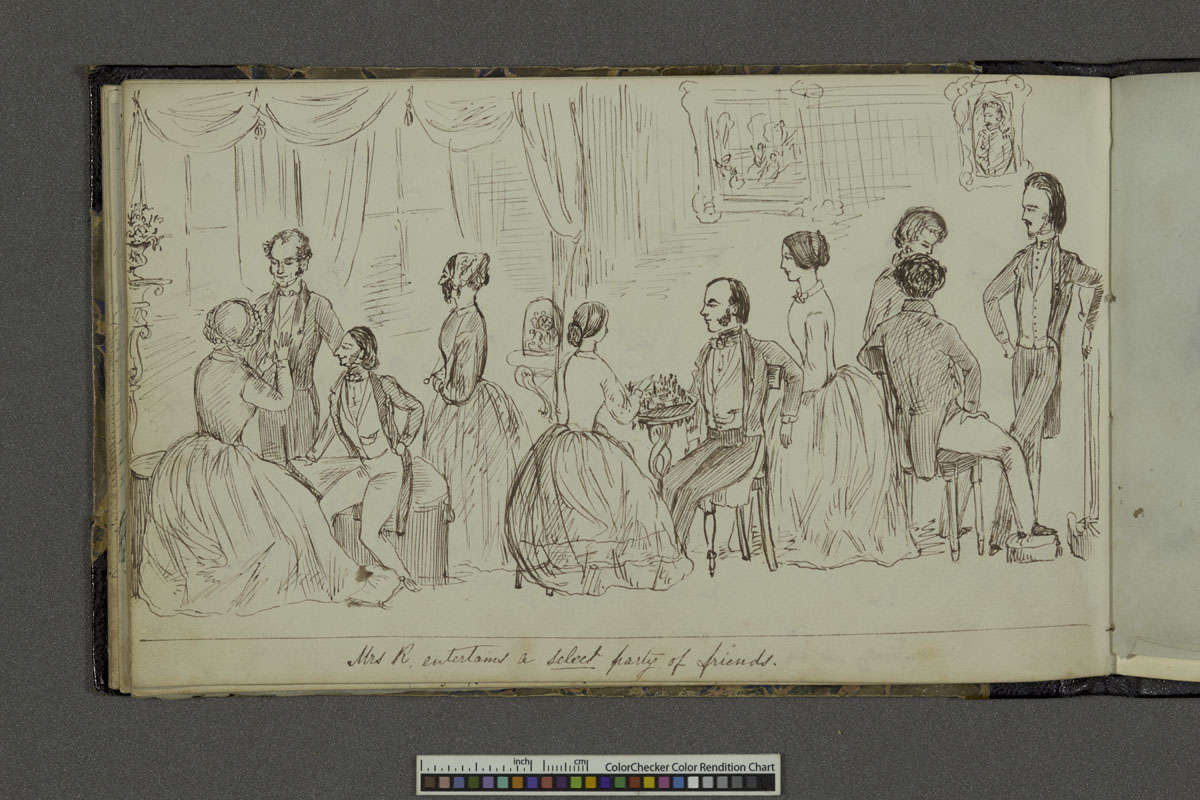

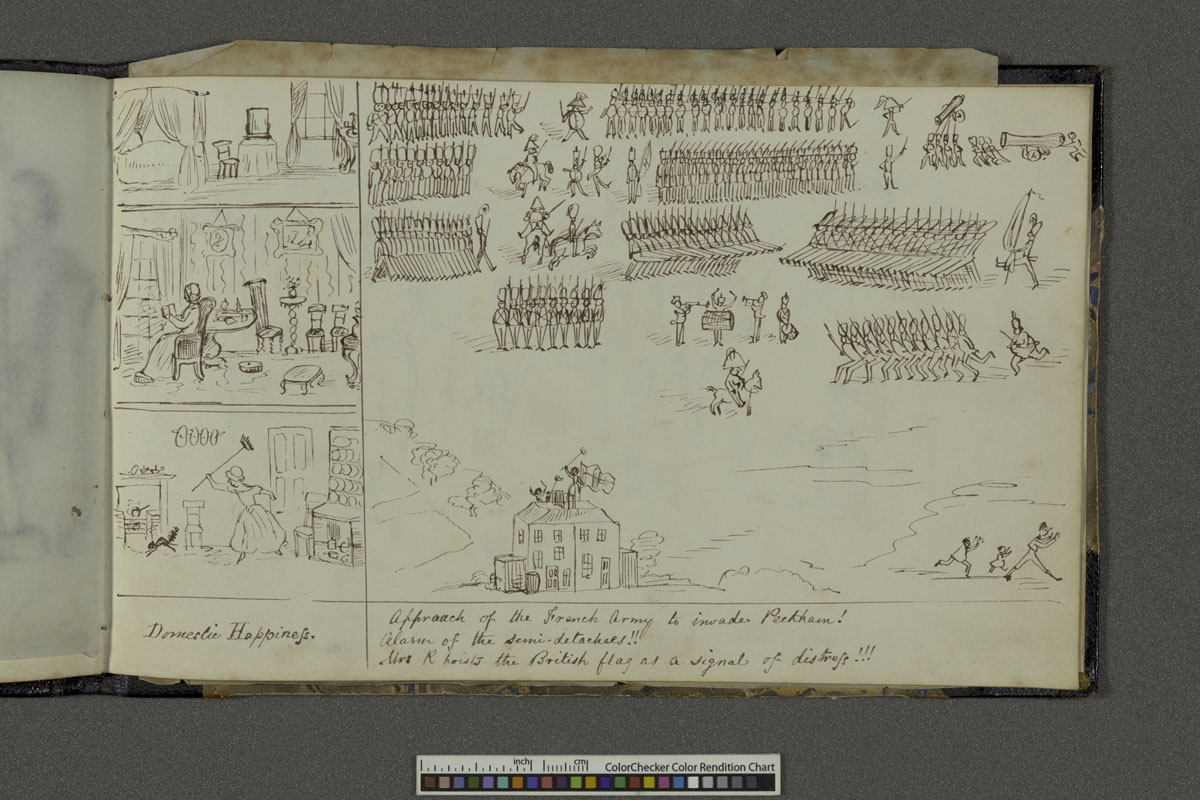

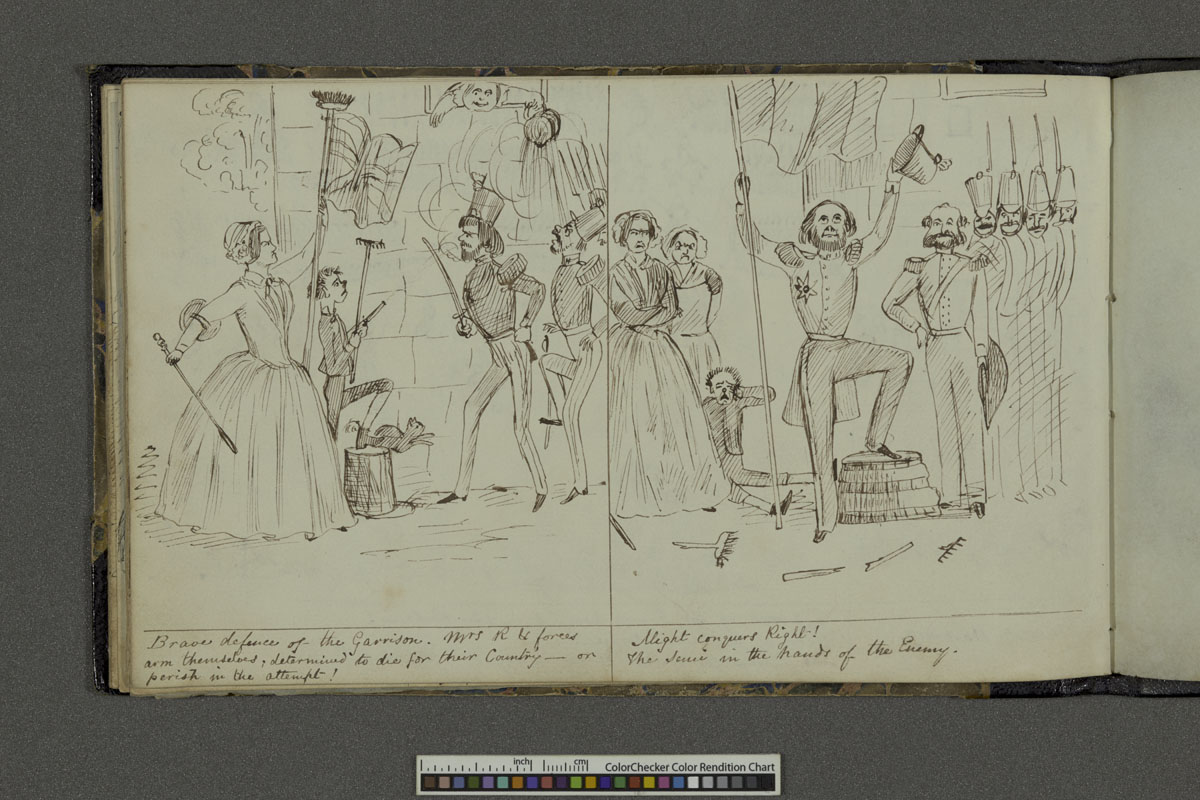

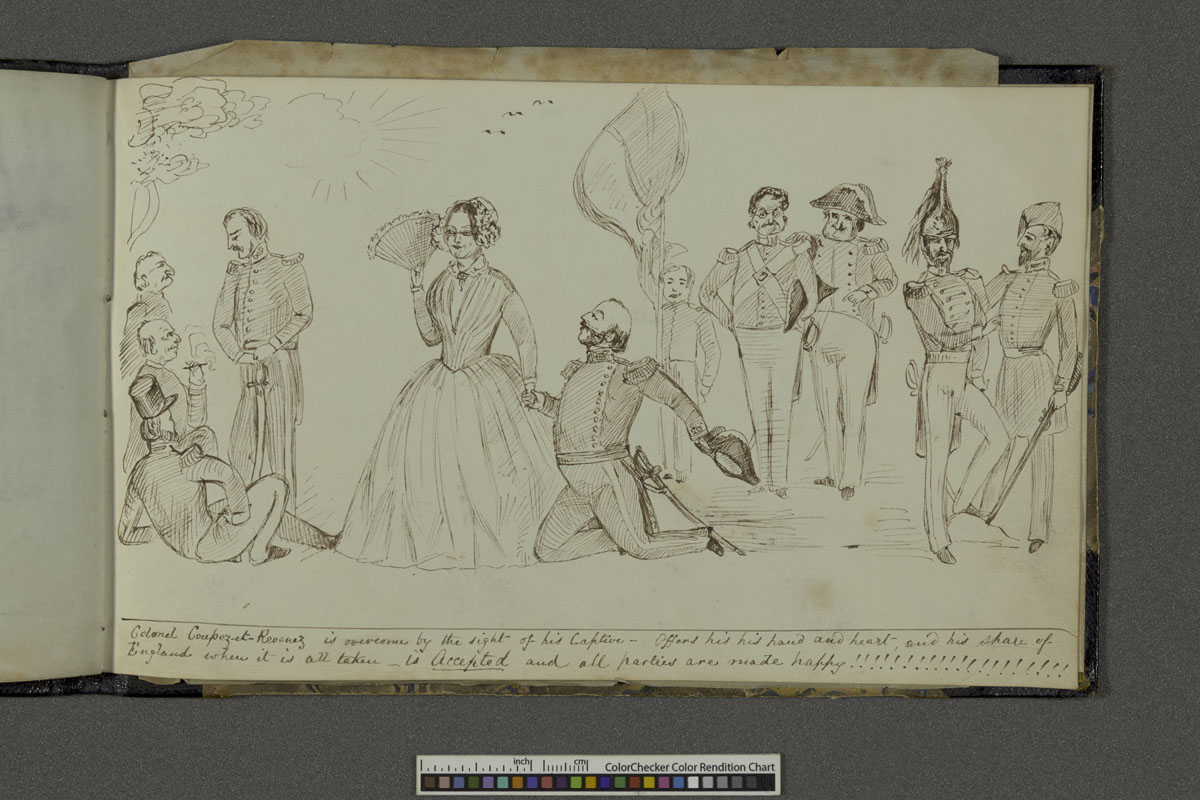

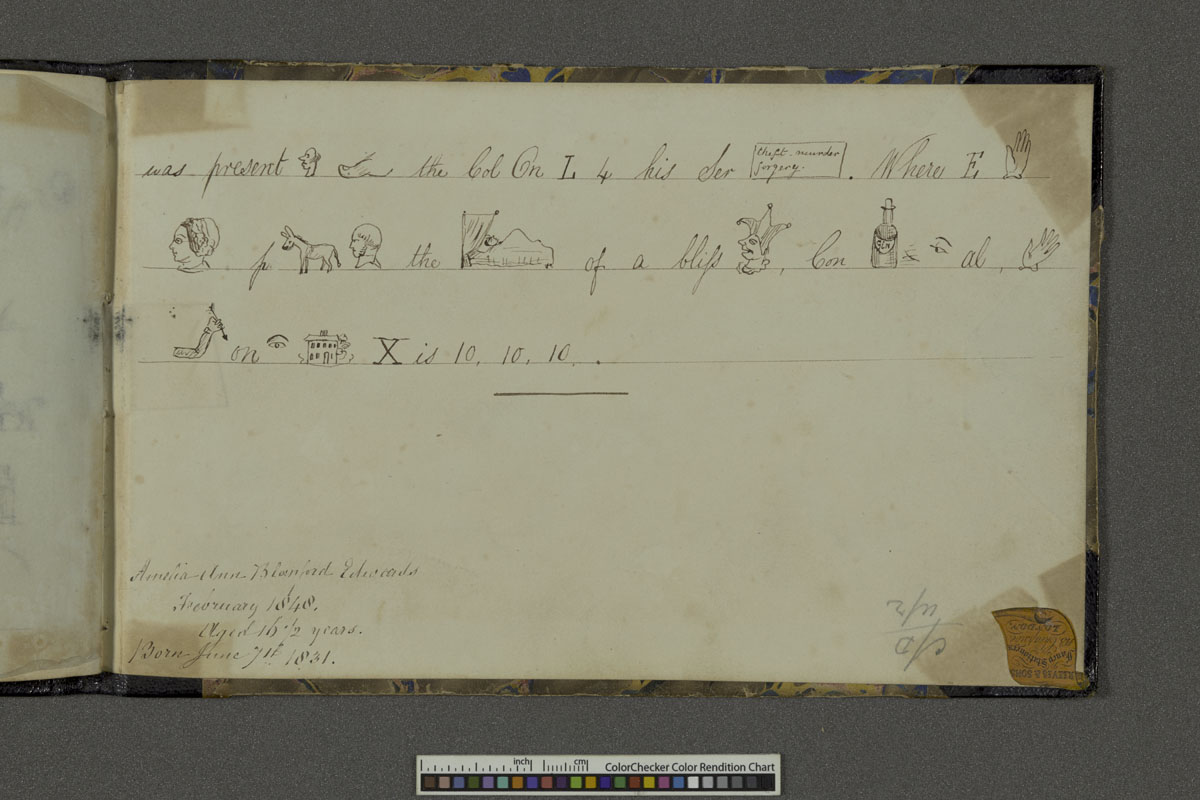

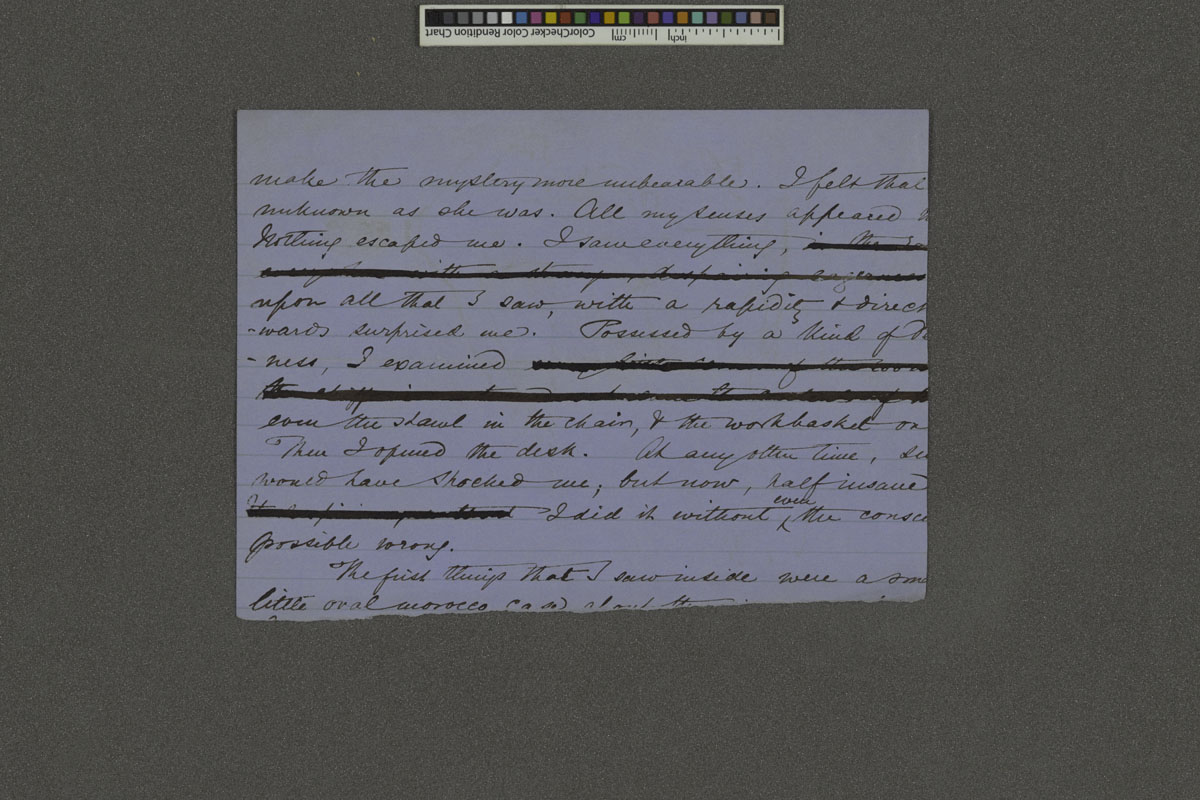

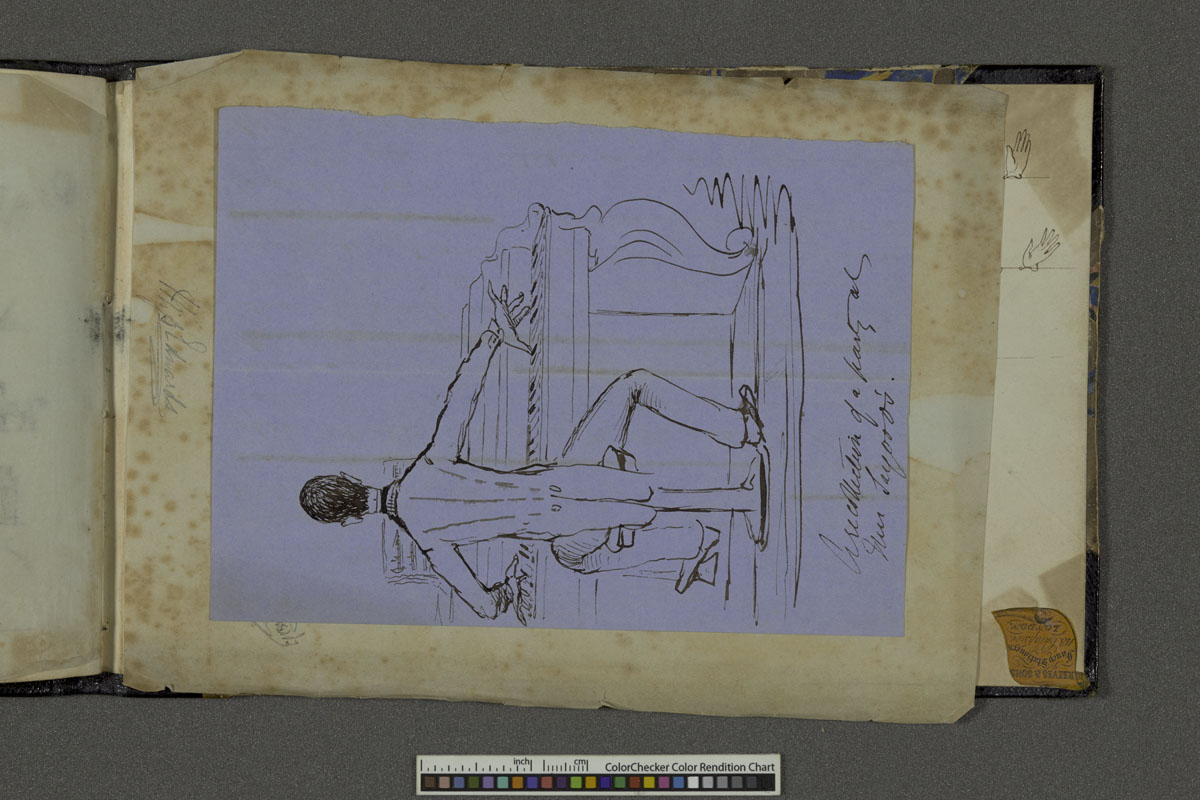

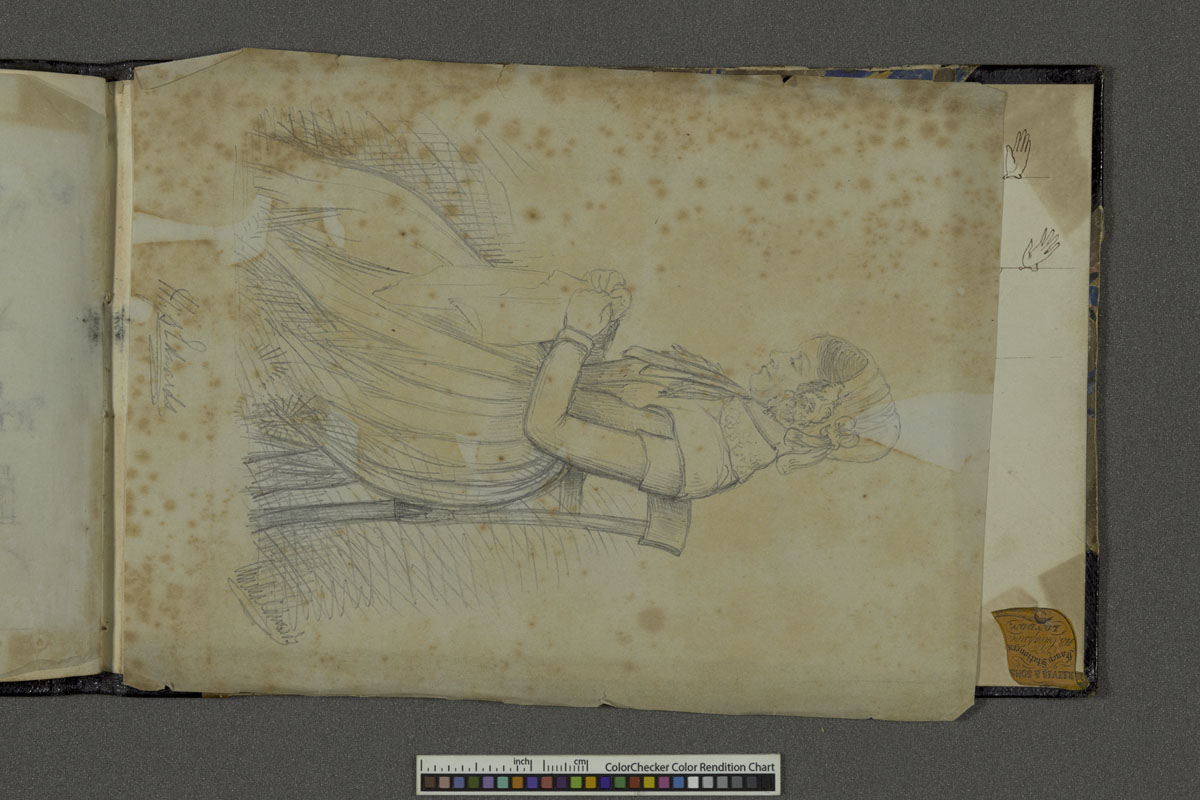

Her letters and recollections (contained in her papers in the Archives) confirm her voracious reading habits as well as her love for drawing: she started writing stories both for her family and the penny press in childhood, many of which she illustrated. The College is fortunate to own Mrs Roliston (recently added to the digital Bodleian site), written when she was 16 and which depicts the adventures of a formidable middle-aged woman who decides to travel and experience life – the drawings are detailed, accurately rendered and with a strong sense of humour: when first one horse, then the other, then the driver freeze to death on the road to Moscow, Mrs Roliston is depicted clutching a bottle of alcohol, “she does not even find consolation in her travelling stores” (see the 8th image below)

Mrs Roliston, written when Edwards was 16 (ABE 424, in the College Archives)

Writing career

Having trained and worked as a musician and organist, she first became known as a novelist, determining to carry on as an author when her story Annette (1853) sold to Chambers’s Journal for £9: it was not so much that it sold for that amount (more than her previous stories had ever made for her), rather that it was a “respectable” journal.

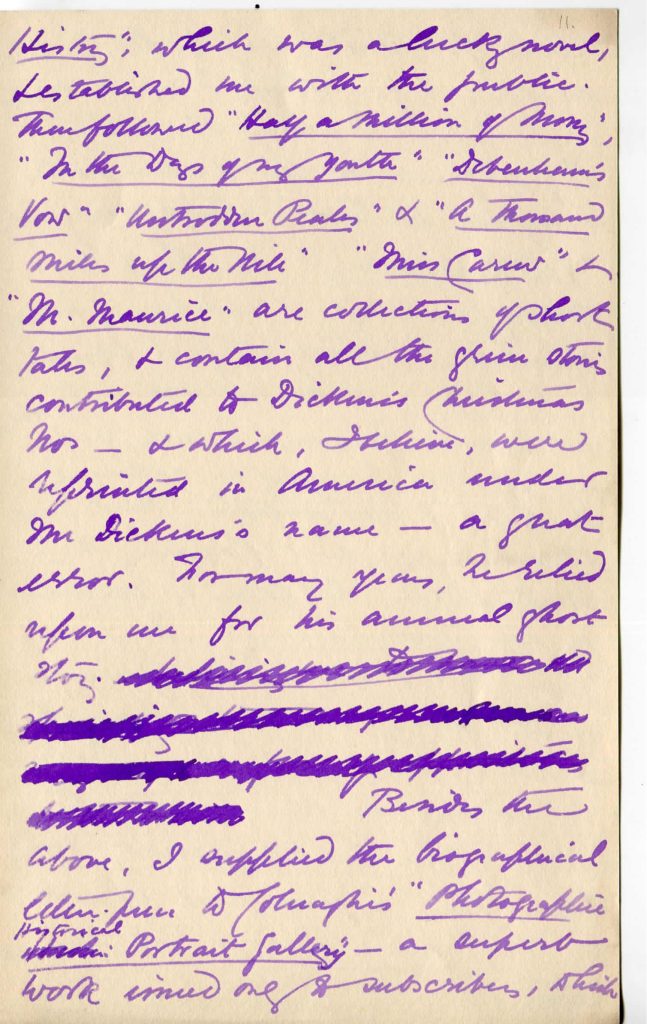

While her novels are now largely forgotten, they were incredibly popular and acclaimed at the time – they often feature sensation of some sort, putting her in a similar school to Wilkie Collins and Mrs Henry Wood (but ‘far above the Mrs Braddon school’ (The Standard, 4 April 1866)), but what set her apart was evocative descriptions of scenes and the ability to encapsulate moods and settings. Her writing is lively and flowing, exhibiting wit and humour: Edwards noted (in a biographical sketch written for an American audience) that some of her (ever popular, even now) ghost stories had incorrectly been presumed to have been written by (and sold in America under the name of) no less a personage than Dickens, and “For many years he relied upon me for his annual ghost story” (in his capacity as editor of Household words) (see below)

Another feature of her novels is the educated environment: her characters read good literature, visit museums and art galleries, have musical or artistic skill and are interested in antiquities. Perhaps this reflects Edwards’ own life and interests: when writing her early novels, she was travelling frequently in Europe, coming into contact with artists, sculptors and intellectuals.

She made notes and drawings in her diaries (some obviously with the thought of turning them into literary pieces), and a hallmark of her writing (as contemporary reviewers commented) is how well researched it is, be it her journalism, her novels, her travel writing or her later Egyptological work.

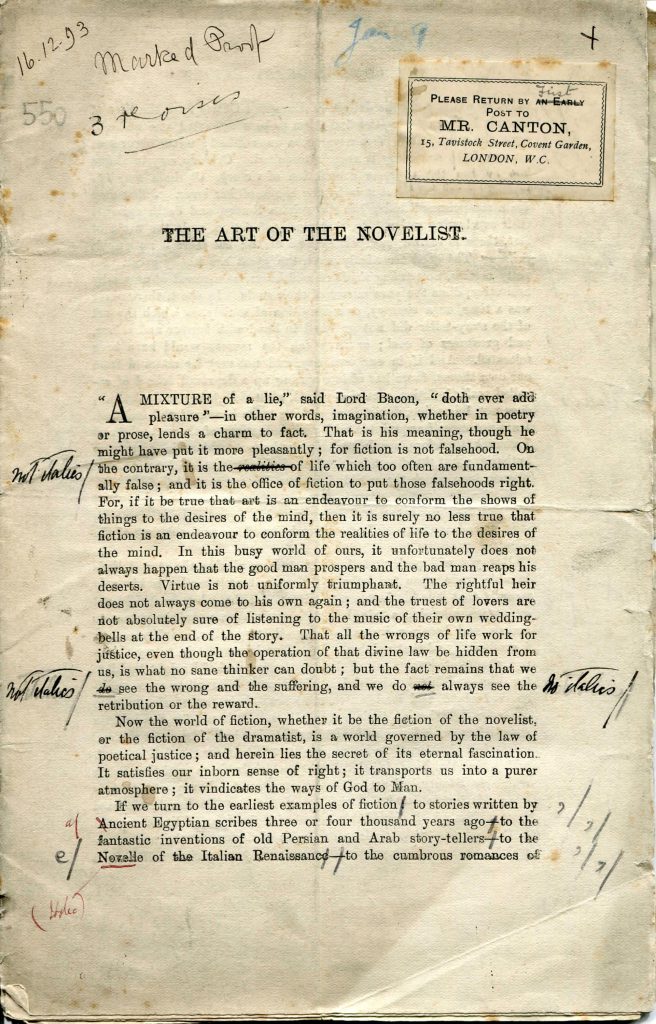

Some years after the release of what was to be her final novel (Lord Brackenbury, 1880) she published an article in The Contemporary Review (vol. 66, Jul. 1, 1894, pp. 225-242) on “The art of the novelist” in which she argues that novels should “paint the living world about us”, that is to say that novels are partly to be seen as reflections of their time and as historical documents, and she is known to have said that she worked hard at her craft, and that her meticulousness was in part because of this conviction (see below). In addition we have a recent reprint of Hand and glove and a collection of her ghost stories, on display in the loggia exhibition.

Reluctant feminist and queer icon?

While her writing perhaps reveals much about her background and taste, it is notable that rarely does one get an unvarnished opinion or much of a revealing nature of Edwards’ internal life [whether we need or ought to look for it is an open question]. She was noted by her cousin (and author) Matilda Betham Edwards as having had from an early age “the perilous dower of personal fascination. No one ever exercised stronger influence…”, and she corresponded with a seemingly vast number of people, many of them notable in their fields (she did in fact keep an autograph book and accounting of all the worthies that she had met and exchanged pleasantries with), but in her collection of letters at Somerville there are very few of her own, and so even here, in her own personal archives, she is curiously absent.

There has, though, recently been a lot of interest in Edwards’ sexual identity, and her grave (see image below) was registered as a site of Historic Queer Importance in 2014.

She shares this grave with Ellen Braysher, an older woman and lifelong companion from the time of the death of Amelia’s mother and Ellen’s daughter – the latter also interred in the same site; they lived together in Westbury-on-Trym for nearly 30 years, until both women died within months of each other in 1892.

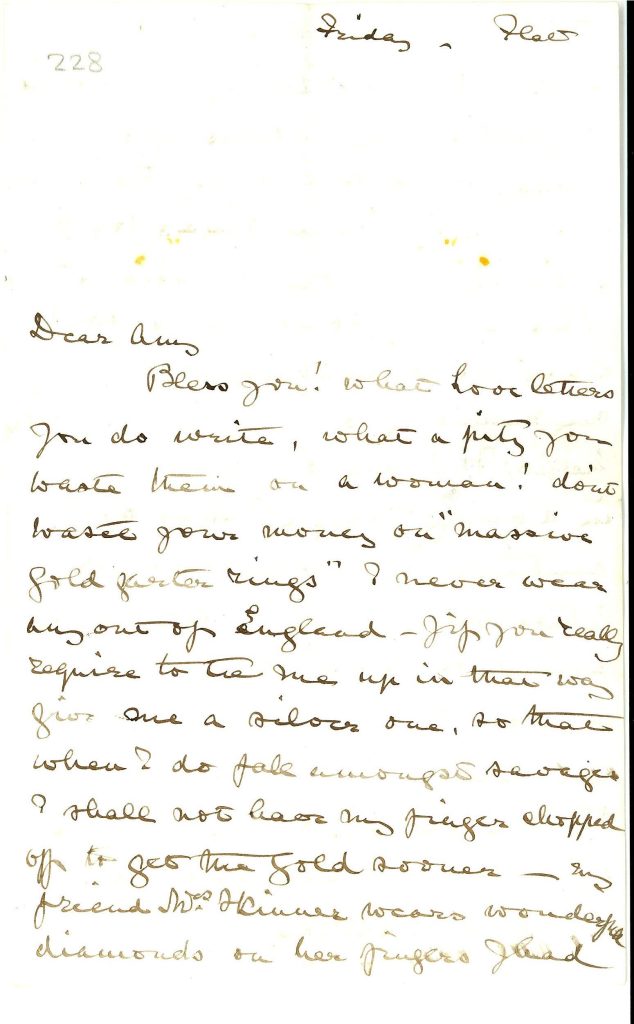

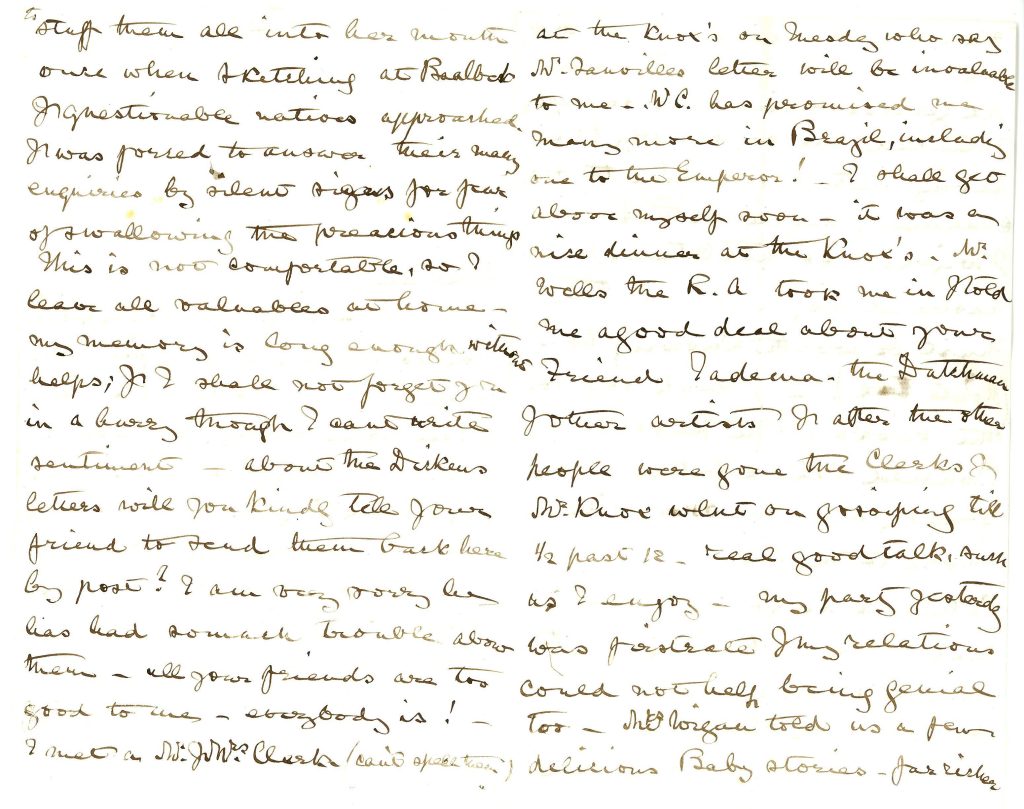

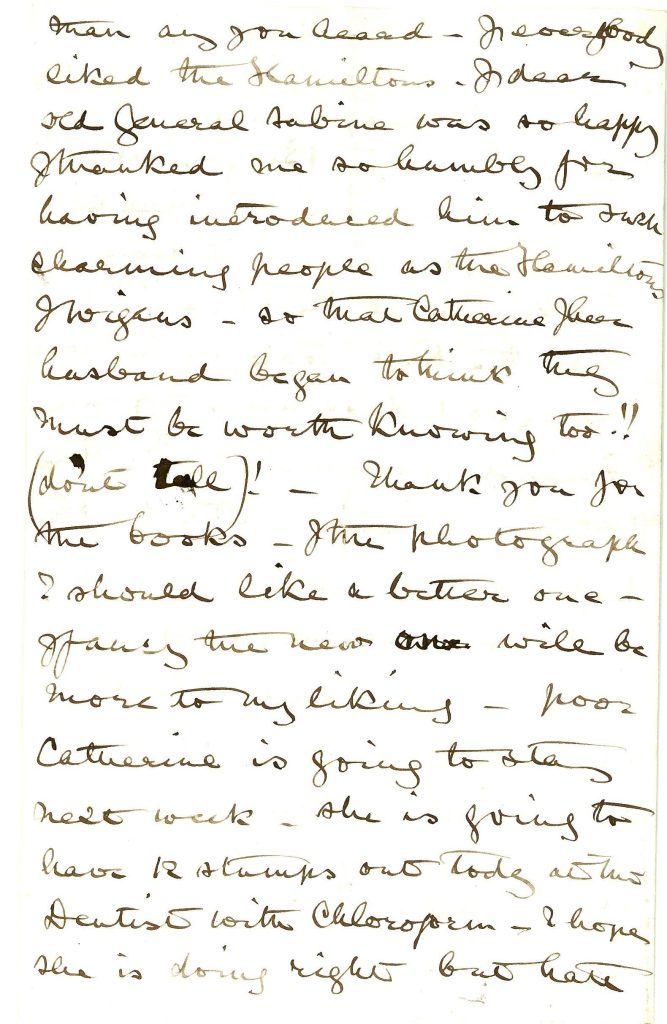

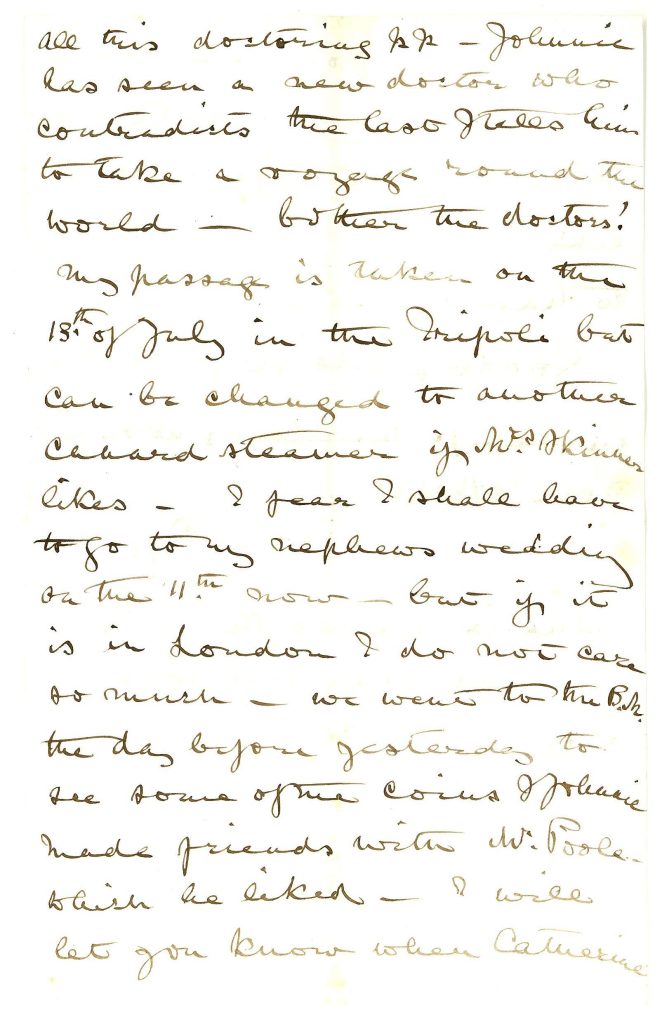

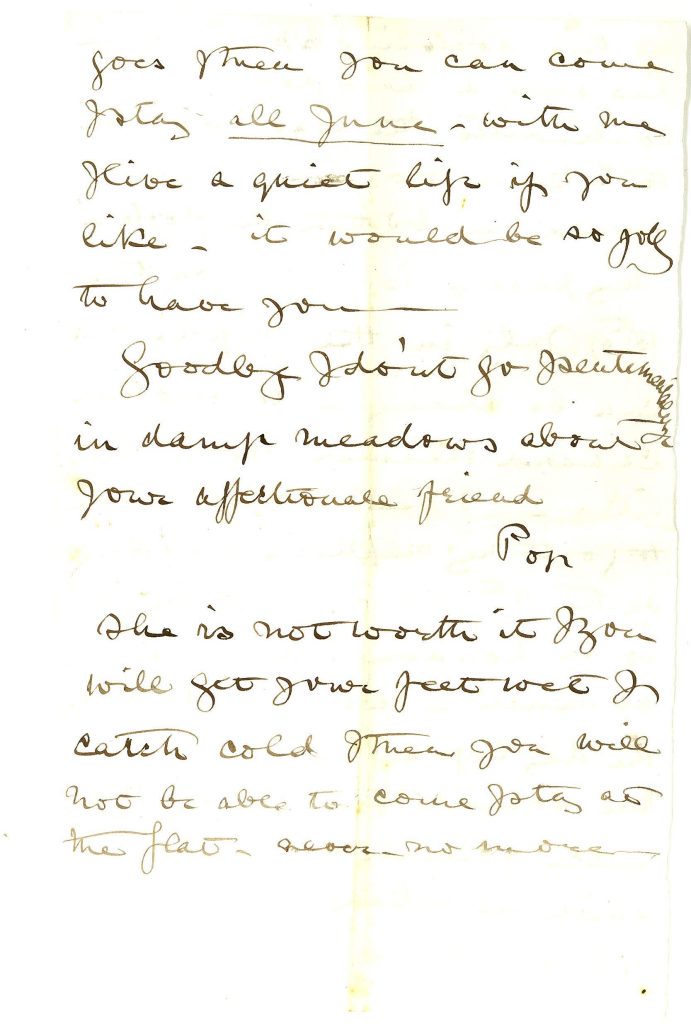

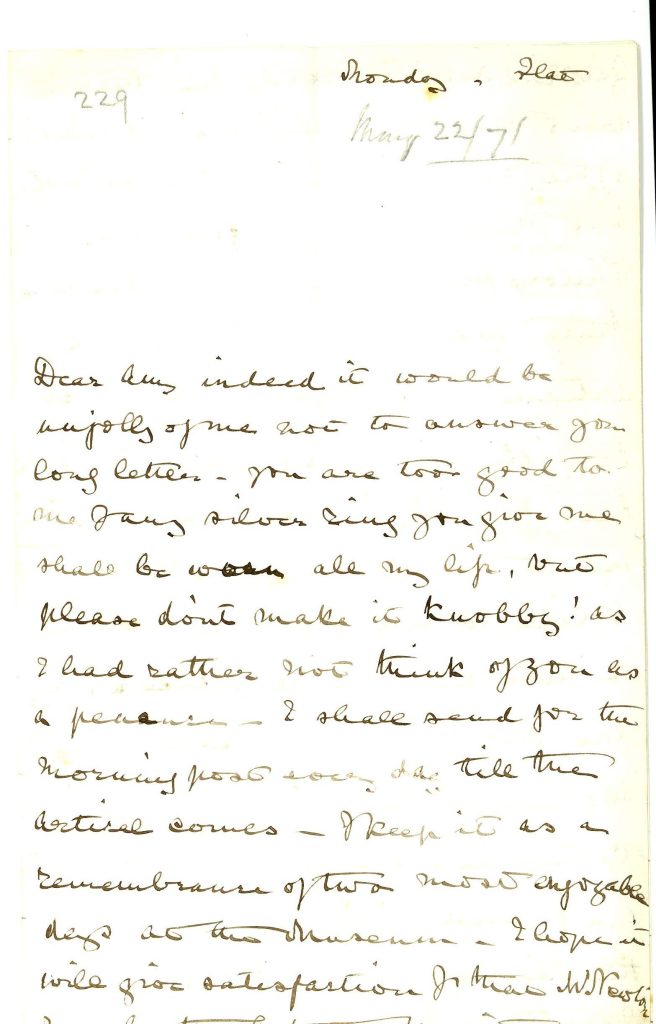

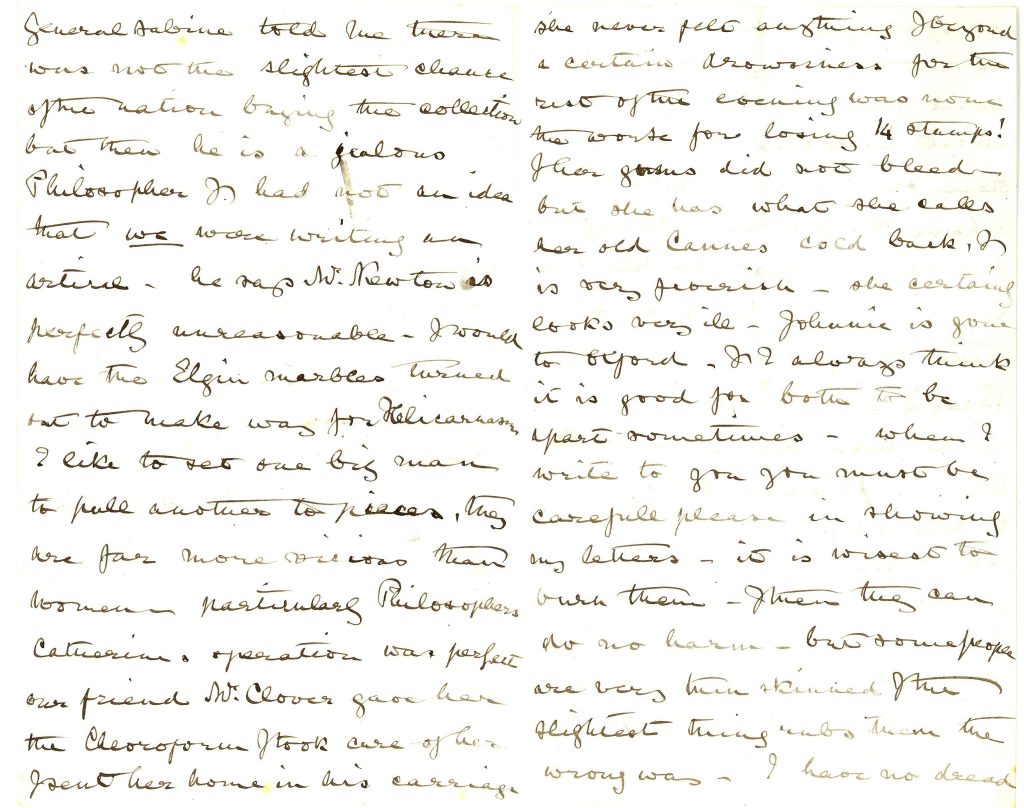

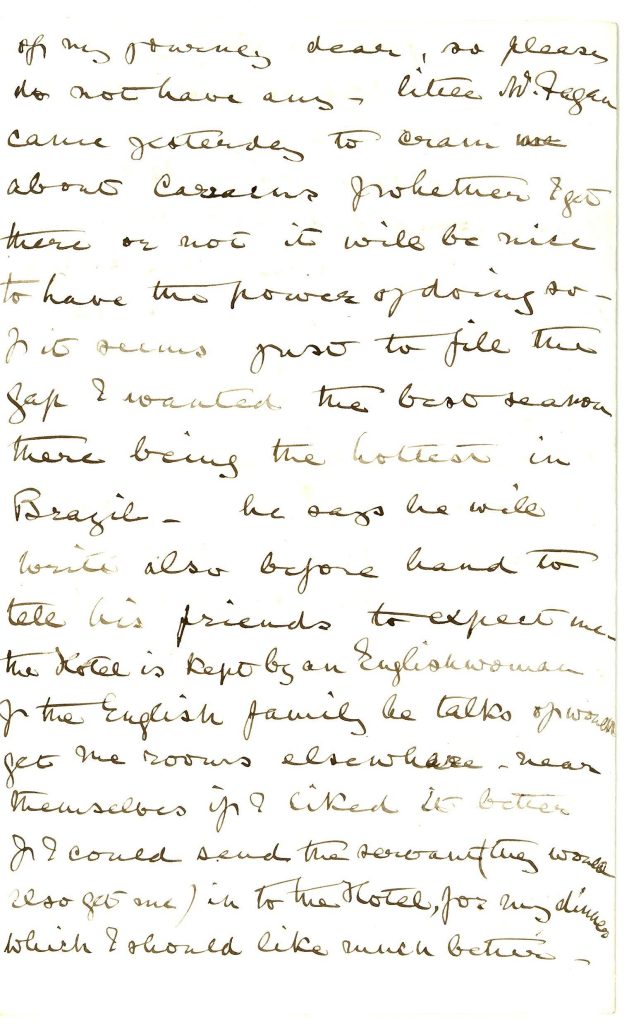

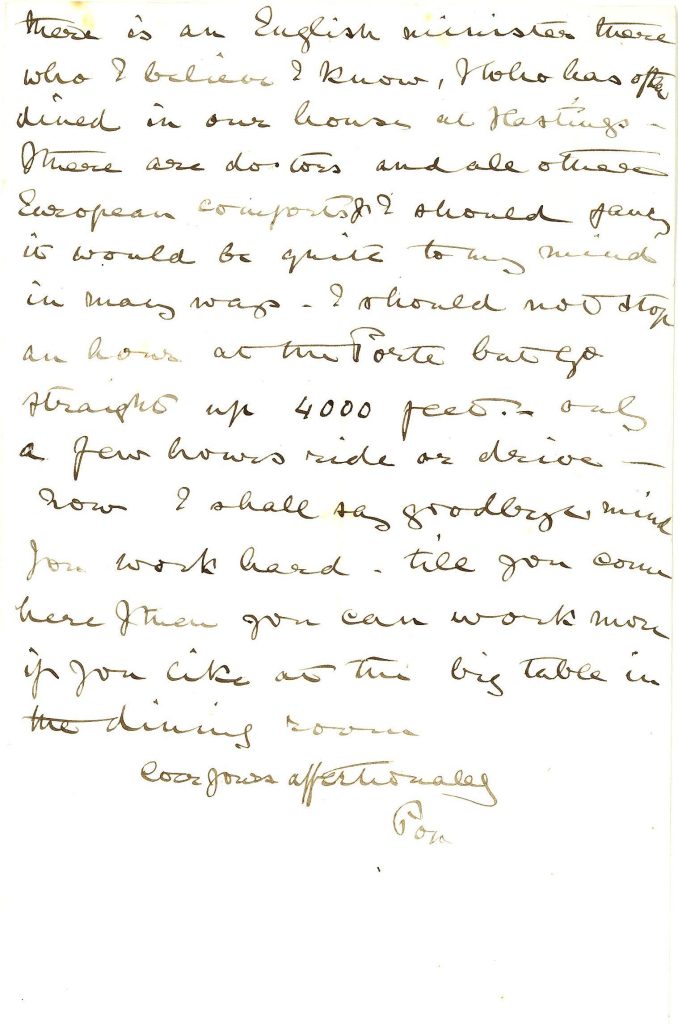

We have some correspondence and the recollections of several of the women with whom she was close. Marianne North (see letter below) seeks to dampen Edwards’ ardour and comments, “What love letters you do write, what a pity you waste them on a woman!” This and the recollections of Kate Bradbury, held at the Griffith Institute, and in which Edwards refers to herself and Bradbury respectively as “poo Owl” and “my sweet own darling Baby love-bird”, might suggest more than just platonic attachments, even when taking into account the way in which close female relationships might have been expressed in this period.

There was an early broken engagement, but Edwards often expresses antipathy for marriage in Victorian England, both in her novels and their female characters, in correspondence and also the way in which she forged a career as a writer – something she was adamant would have been impossible inside the bo(u)nds of traditional marriage (a good example of this is her attitude toward the married couple in One thousand miles up the Nile, in which Edwards also fashions a very clear persona as “the writer”)

Letters ABE 228 and 229: Marianne North to Amelia Edwards

This attitude to marriage and the difficulty in pinning Edwards down as queer is also suggestive of her attitude to women’s suffrage: her biographers largely call her a “reluctant feminist”, but it is worth noting that she was known for her ability to steer a diplomatic path through troubled waters – either when dealing with personal matters, when cajoling support for the Egypt Exploration Fund (which she founded in 1882) or when smoothing the ruffled feathers of the jarring personalities involved. An obituarist wrote that she did all this, “never expressing a strident view” or engaging in “faddism”: this is a not-so-veiled reference to feminism. Tactful seems a more helpful word than reluctant here, especially when we consider that she was a signatory to John Stuart Mill’s bill to Parliament on female suffrage, that she supported women’s charities, donated her books to a women’s college, had one of her books printed by an all-woman press (specifically set up to provide employment opportunities for them) and her egalitarian approach to education: she chose UCL as the place to bequeath the majority of her Egyptological collections because of its stance of allowing both men and women to study.

“The Queen of Egyptology” (American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal (Nov. 1892))

Interest in Edwards’ sexuality and her relationship with feminism and suffrage is of fairly recent vintage, but her position in the history of Egyptology has long been acknowledged (see the title of her obituary that I have used for this section!)

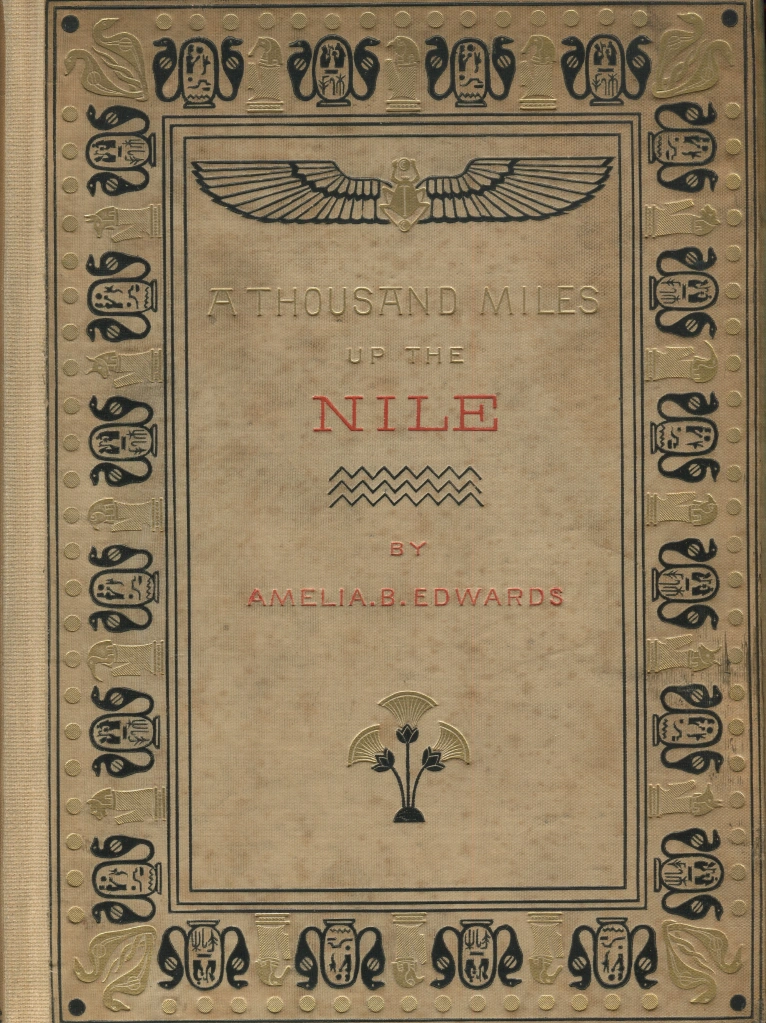

Egypt Exploration Society (founded by Edwards in 1882 as the E.E. Fund) is shortly to publish a new edition of her classic and much admired 1000 miles up the Nile, a historical and archaeological travel book of her journey in Egypt in 1873-4. In keeping with her previous writing (both the novels and her account of her travels in the Dolomites published in 1873), Edwards took pains over her research upon her return, taking 2 years to write the book, and corresponding with notable Egyptian experts (eg. Dr Birch at the British Museum, about hieroglyphs) and enriching the text not only with copious references to the latest scholarship, but also her own keenly drawn watercolours of the scenes, places and people she had encountered.

She is rightly remembered as a watercolourist, and Somerville has supplied the EES with the images of her original plates for 1000 miles for their new edition. Some of her drawings and watercolours can be seen on display in Green Hall, along with our copy of the book (front cover below)

Her experiences in Egypt and her work in preparing 1000 miles for publication (and re-publication: she added much new referencing and footnoting for the second edition) had made Edwards aware of the wholesale depredation taking place in Egypt, and she became determined to stop the theft of and damage being done to these antiquities (although she ended up with a large personal collection of said antiquities herself, possibly indicating that she held, however unconsciously, the common colonial, paternalistic attitude about how best to conserve archaeological finds).

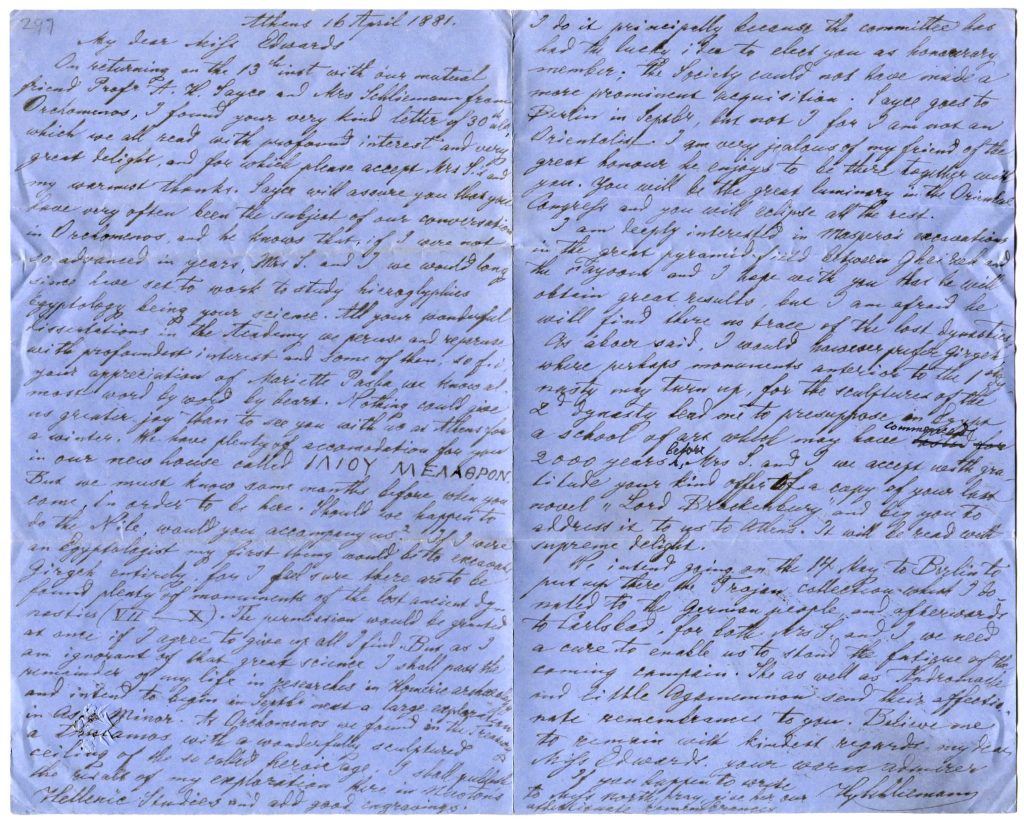

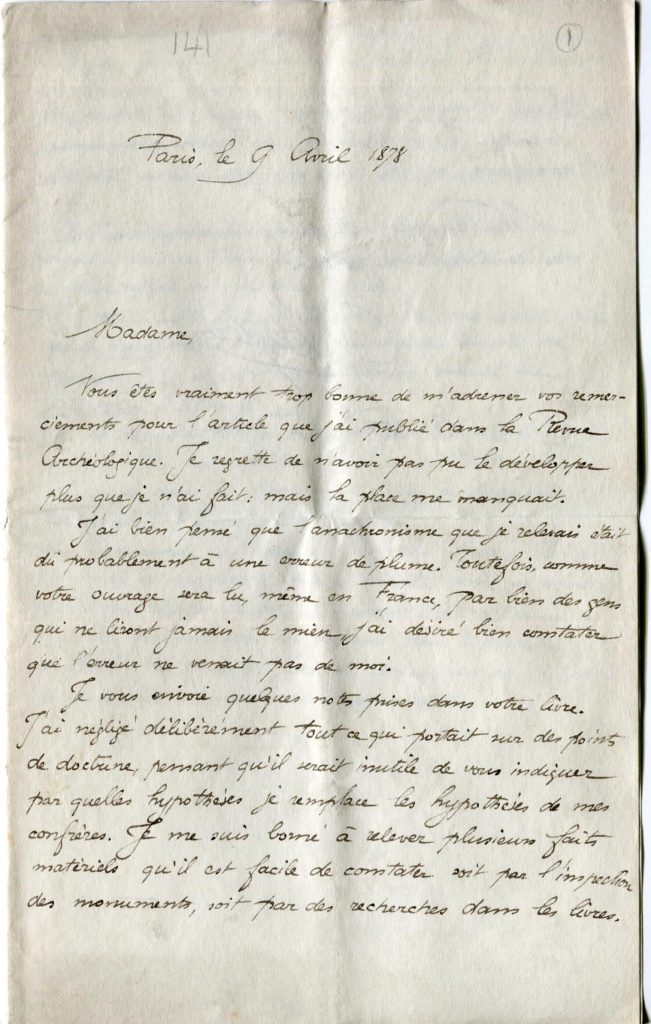

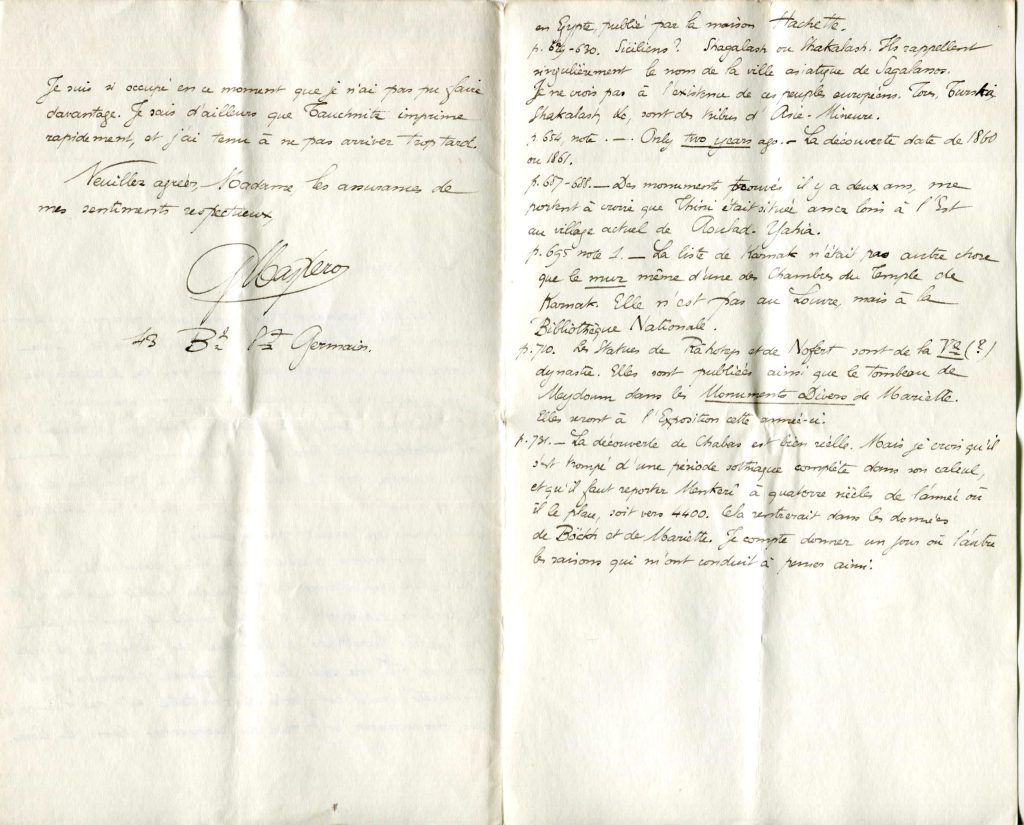

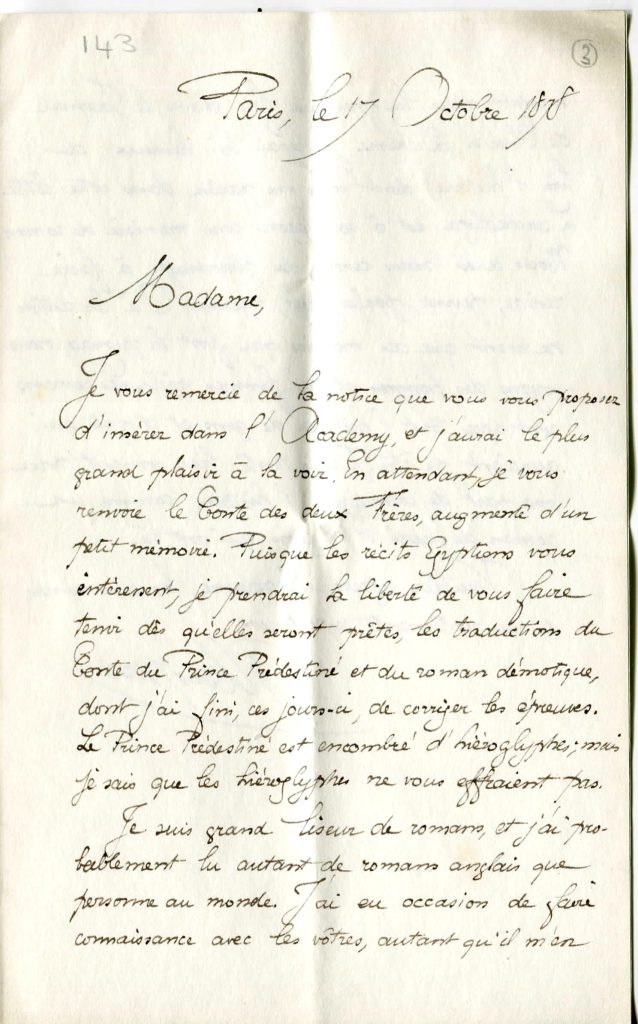

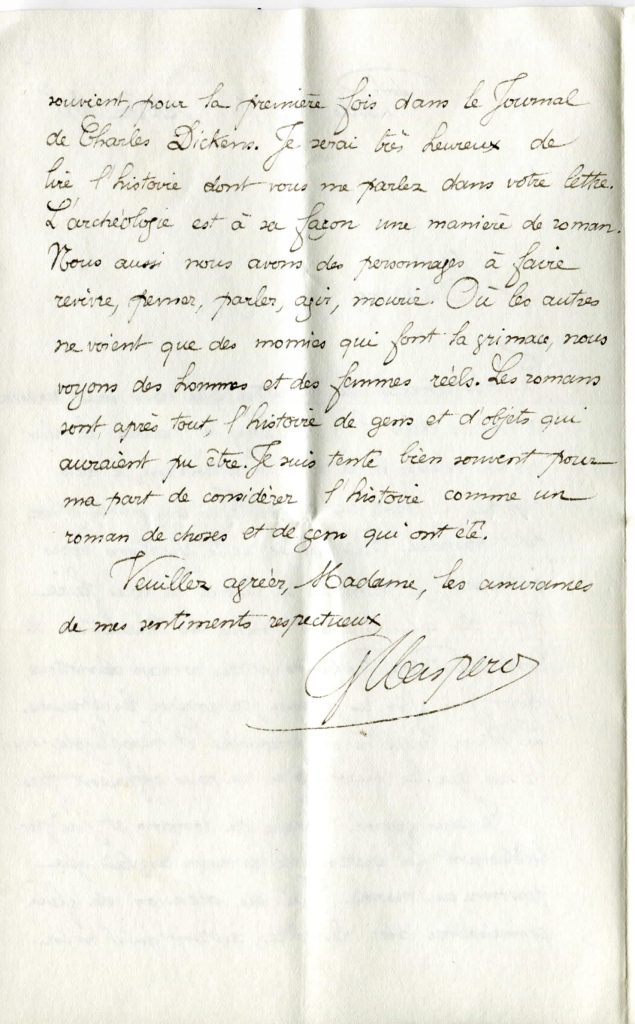

Her way of doing this was, as ever, to use her network of contacts to foster a desire for the preservation of ancient Egyptological artefacts amongst the public and to encourage those working in this nascent science: she advertised widely, corresponded with thousands of potential donors, wrote up reports of work being done and added her own scholarly writings to the field. In doing the latter, notably with the publication of 1000 miles, she came into contact with archaeologists Edouard Naville, Gaston Maspero and, finally, Flinders Petrie, who would take up the Chair at UCL that was set up from Edwards’ bequest.

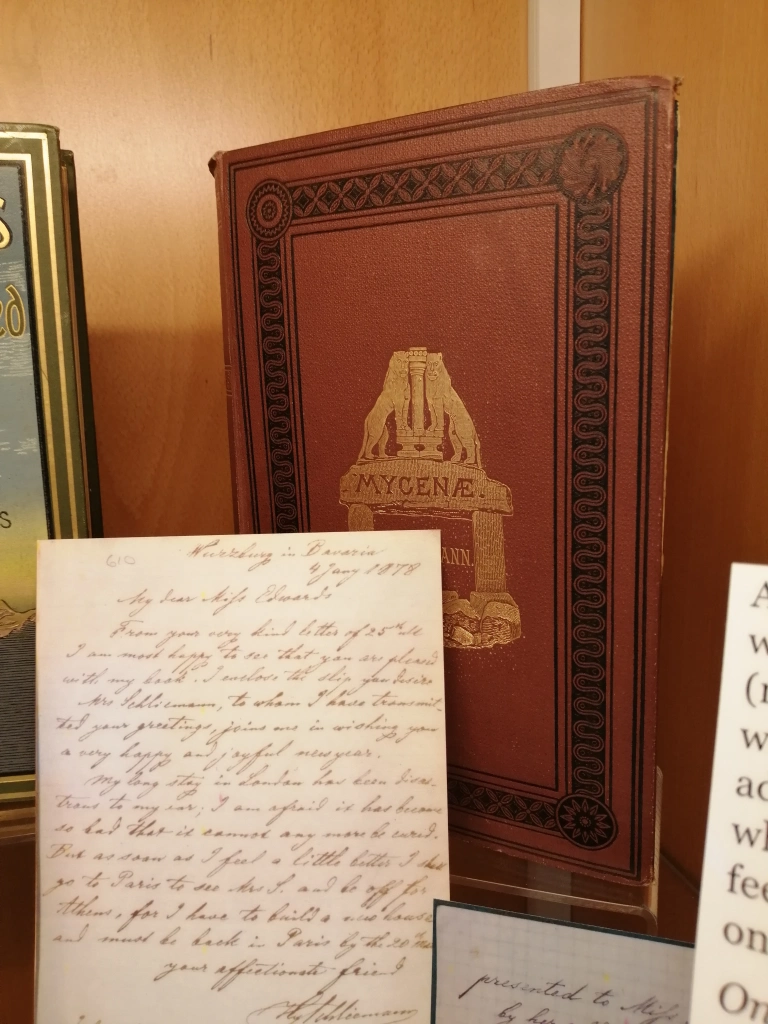

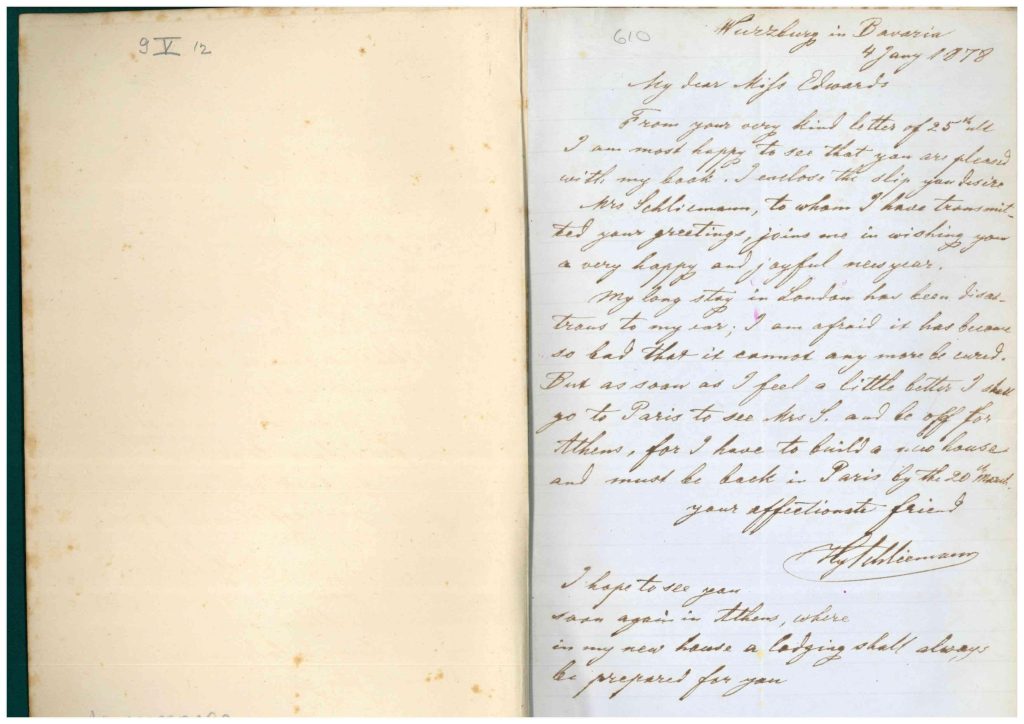

Her correspondence with all of these men is very revealing, not only of their personalities, but the rapid progression of the science (see the Schliemann letter above in which he refers to Egyptology as “your science”) and of the different opinions as regards methodology: what we now take for granted as the way that archaeology is done was in very great part down to Edwards and the very profitable relationships and correspondence which she had with Maspero and especially Petrie. Maspero was very dismissive of Schliemann’s methods and all the razzmatazz surrounding his Greek ‘discoveries’ (possibly some sour grapes), but his opinions chimed with Edwards’, and he was very obviously aware that by her work (and writing in particular) she was having a profound impact on Egyptology as a discipline.

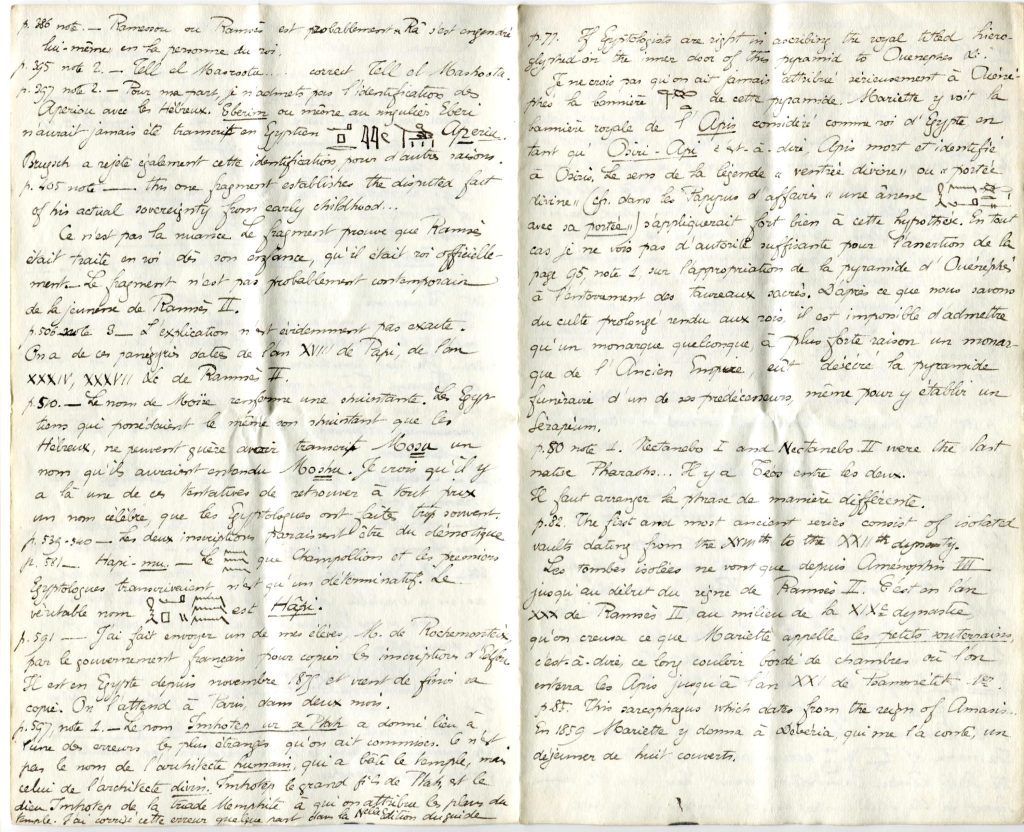

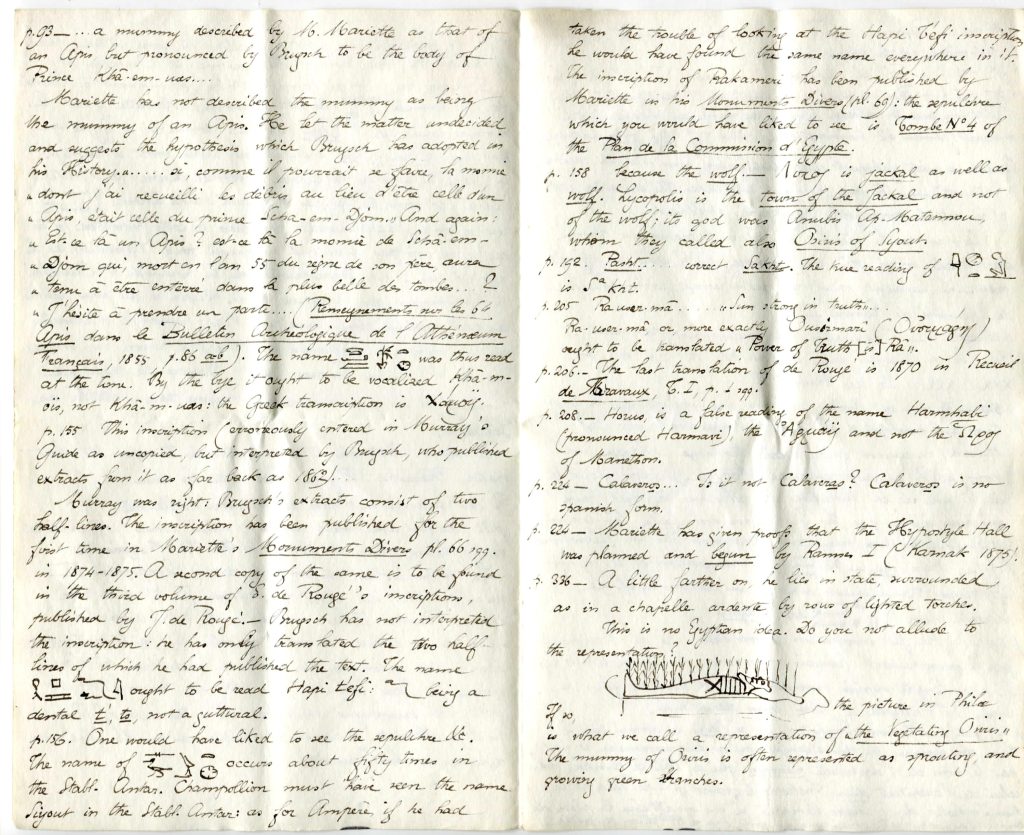

The two letters on display and reproduced below are from early in Edwards’ and Maspero’s correspondence: in the first he compliments her on 1000 miles and then offers a series of elucidations and corrections (you can see his careful transcription of hieroglyphs and the representational figure of a mummy); in the second he praises her for the way in which she brings archaeology and romance (for which read novel writing) together – this would greatly inform the development of archaeology and specifically Egyptology, and was a great reason for Edwards’ success.

On display in the exhibition are also Edwards’ translation into English of Maspero’s Manual of Egyptian Archaeology and an excerpt from her preface where she talks of bringing ancient Egypt to life through such works as this.

Despite an immensely successful lecture tour in America in 1889-1890, Edwards noted in letters to Petrie that she had lost income by taking up the cause of Egypt and is recorded by Kate Bradbury (again in letters held at the Griffith Institute) as having been in tears when learning of her award of a state pension for services to Egyptology. Her grave (see above) also acknowledges this obsession of the last third of her life, having both an obelisk and an ankh, and it is for her contribution to Egyptian archaeology that she will continue to be remembered.