Book of the term

Every term we feature a rare and interesting item from our collection.

Hilary Term 2026

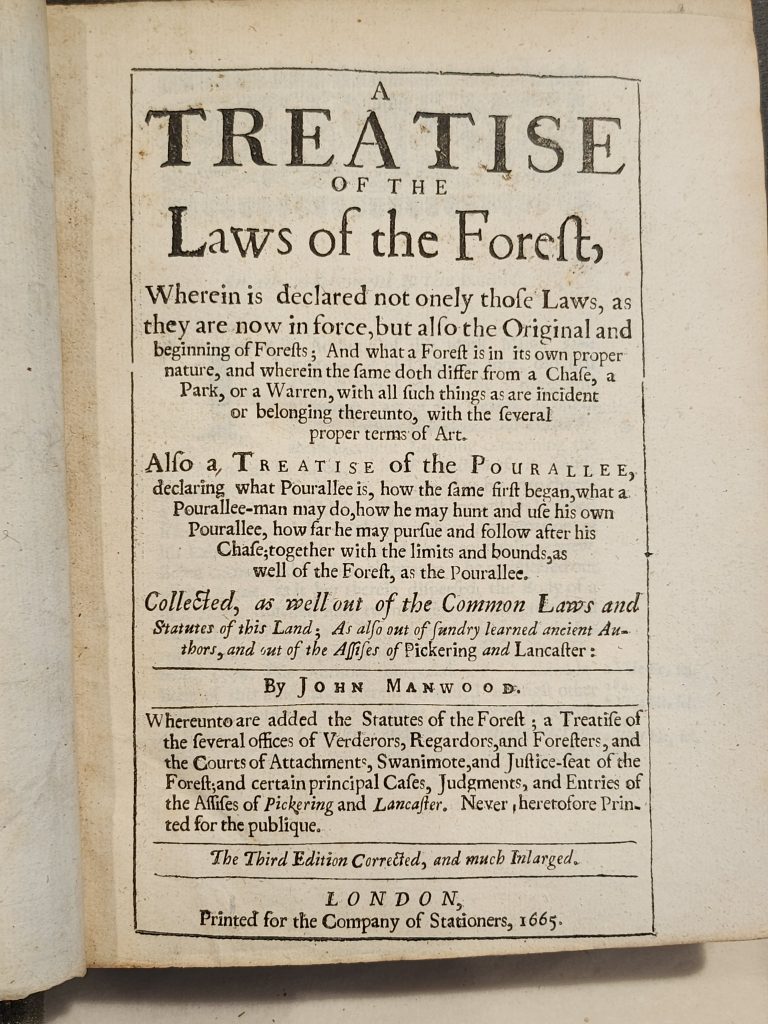

A Treatise of the Laws of the Forest

by John Manwood

What is a forest? We generally think of it as an area of dense woodland, more extensive than a wood – but anyone going to the New Forest, in southern England, expecting to see mile after mile of tree-cover will be disappointed, as roughly half of it is open pasture and heathland. The book displayed here defines a forest as ‘a certaine Territorie of wooddy grounds and fruitfull pastures, privileged for wild beasts and foules of Forest, Chase and Warren, to rest and abide in, in the safe protection of the King, for his princely delight and pleasure’ – and it is this use as a royal hunting preserve, rather than the landscape itself, that originally defined the areas of England which were designated ‘forests’. They were also distinct in that within their boundaries a separate body of law known as forest law applied, which had its own officers and courts.

Forests and forest law were an innovation introduced by William the Conqueror after the Norman Conquest in 1066. Large areas of England were arbitrarily declared by the king to be ‘forest’, with harsh laws to protect the ‘venison and vert’ (the game animals and the vegetation they needed for food and cover), which caused great hardship to those who happened to live there and had been accustomed to making use of the natural resources around them. Penalties ranged from fines to blinding, castration and even death, not only for killing the king’s deer and boar, but also for offences such as felling a tree for firewood, clearing land for crops, or carrying a bow and arrow. Cases were brought first to the court of attachment, or woodmote, which was held every forty days. This had no powers to try or convict, other than to impose small fines; those brought before it were ‘attached’ to appear before the swainmote. This was held three times a year, and as well as trying offences against forest law decided matters such as when domestic animals could be turned out to forage in the forest. Those indicted by it had to wait for the Court of Justice in Eyre, held in theory every three years but in practice much more erratically, for judgement to be passed on them. This cumbersome system was administered by a host of officers including verderers, foresters, agisters and regarders.

William’s immediate successors continued his policy of creating forests by royal diktat (regardless of who actually owned the land) in which the right to hunt any animal belonged exclusively to the king. But they and later monarchs also found it useful to grant or sell the right to hunt certain animals, or to cut timber or grow crops within certain areas, in order to win support or to raise revenue. So the royal forests, and the jurisdiction of forest law, fluctuated and became fragmented, with the addition of warrens, chases, and purlieus, in which some or all of forest law no longer applied. Over time, other pressures came to bear: an increasing population meant more land was required for agriculture, and more timber for building; the royal forests also became an important source of oak for warships. It was found prudent not to enforce forest law, and the harsh penalties it prescribed, too strictly, in order to keep the inhabitants happy. Hunting also changed. For early medieval kings, it, and the enforcement of forest law, could be seen as an assertion of their sovereignty; it was also preparation for riding on the battlefield. For Tudor monarchs, it was a princely sport governed by a code of etiquette, a chance to show their courtly culture. Thus by 1598, when the work displayed here was first published, its author, John Manwood, could state: ‘The Forrest Lawes are growen clean out of knowledge in most places in this land’.

The early Stuarts tried to reassert their royal hunting prerogative: James I was keen to the point of obsession on hunting; Charles I was desperate for the money he could raise by reviving long-defunct courts and fines. Under Charles II, the hunting of game became the exclusive right of all landed gentry, not just the monarch, and over the succeeding centuries laws were focused on the prevention of poaching rather than the preservation of forest. But it was not until the Wild Creatures and Forest Laws Act 1971 that forest law (with a few exceptions) was formally abrogated and the right of the monarch to claim ownership of wild animals and set aside land for them was abolished.

Very little is known about the author of this treatise, John Manwood; he was apparently a member of Lincoln’s Inn, but he does not appear anywhere in its records so presumably never qualified as a barrister. His treatise on forest law began as A Brefe Collection of the Lawes of the Forest, printed for private circulation in around 1592; in 1598 a revised and enlarged edition of this was published as A Treatise and Discourse of the Lawes of the Forrest. Following Manwood’s death in 1610, a posthumous edition was published in 1615 which included five chapters on the forest courts taken from the private edition which had been omitted from the Treatise; this was reprinted in 1665, and it is a copy of this edition which is on display here. A fourth edition was produced in 1717, reprinted in 1741, with the material rearranged under alphabetical headings.

This copy of Manwood’s Treatise was given to Somerville by the family of Sir Edward Fry, a distinguished lawyer and judge, and father of Margery Fry, Principal of Somerville 1926-1931.