Previous book of the term

Michaelmas Term 2021

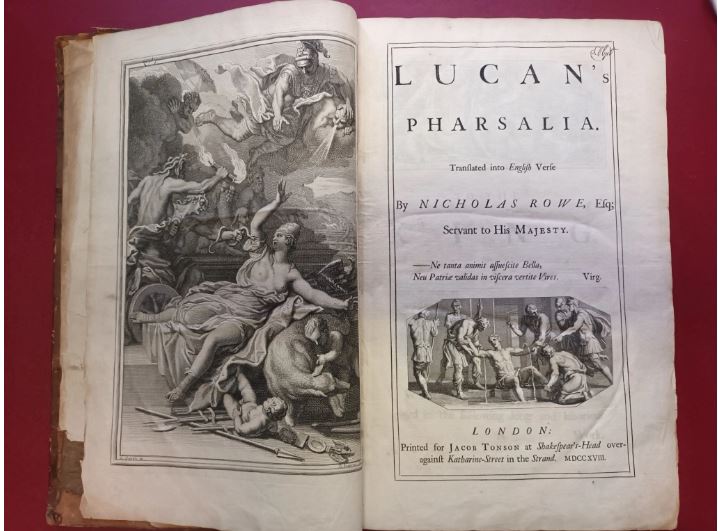

Lucan’s Pharsalia Translated into English verse by Nicholas Rowe

The Roman poet Lucan (Marcus Annaeus Lucanus) was born in the Roman colony city of Corduba (now Cordoba) in southern Spain on 3 November 39 CE. When he was less than a year old, his father moved the family to Rome, where Lucan was educated as befitted a member of the elite, with an emphasis on literature and rhetoric. In 49 CE his uncle, Lucius Annaeus Seneca, was appointed tutor to Nero, who became Emperor on the death of his adoptive father Claudius in 54 CE; Lucan, who had gone to Athens to continue his studies, was recalled by Nero to become one of his inner circle of trusted friends and advisors. In 62 or 63 Lucan published the first three books of his epic poem De bello civili (On the Civil War, also known as the Pharsalia), which begins with a paean in praise of Nero. But relations between them clearly soured, and in early 65 Lucan joined the conspiracy led by Gaius Calpurnius Piso to assassinate Nero. The plot was discovered, and Lucan was forced to commit suicide (depicted on the title-page of the volume displayed here), as were his father and his uncle Seneca, who were also implicated in it.

Lucan was a prolific writer, but the ten books of the Pharsalia are the only work of which we have a complete text (and that is almost certainly unfinished). Its subject is the civil war which began in 49 BCE when Julius Caesar, at the head of an army, crossed the Rubicon, a stream which marked the boundary between Gaul, where Caesar had been given authority to wage war by the Roman Senate, and Italy, where he had no military authority and therefore to bring an army with him constituted an invasion.

Lucan’s portrayal of the war is as something of unspeakable horror, in which the Roman Republic is destroyed; his attitude is well illustrated by the frontispiece of the volume displayed above. It shows a personification of the city of Rome, accompanied by Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome, with the she-wolf which suckled them, being attacked by the Furies, with serpents wreathed in their hair; above them Mars, the god of war, directs the storm-winds to blow on her; the fasces – the rods and axe which symbolised Roman civil authority – and the eagle-topped military standard lie fallen on the ground.

The translator, Nicholas Rowe, was born in Little Barford, Bedfordshire, in 1674, and at first followed his father by becoming a barrister. But on his father’s death he inherited an income of £300 a year, which allowed him to leave the law and pursue his own inclination, which was for literature and in particular the theatre.

His first play, The Ambitious Stepmother, was produced in 1700, and was set in the imperial court of ancient Persia; his second, Tamerlane (1701), concerned the founder of the Central Asian Timurid empire. Both followed the Restoration fashion for tragedies to depict the great and powerful, and also had strong undertones of contemporary politics. But tastes were changing; his later plays were mostly ‘she-tragedies’ – a term he probably coined himself to refer to plays with a more domestic setting focusing on the sufferings of a woman. His most successful play was The Fair Penitent, described by Dr Samuel Johnson as ‘one of the most pleasing tragedies on the stage’, which brought into popular use the name Lothario to refer to a philanderer.

Rowe also produced the first modern edition of Shakespeare, published in six volumes in 1709, with modernised spelling and punctuation, and for the first time with the dramatis personae listed at the beginning of each play.

Like many of Shakespeare’s plays, Rowe’s plays were written in blank verse, and in 1715 he was appointed poet laureate. His most ambitious poetic venture was the translation of Lucan displayed here, which took him some twenty years to complete. Like his earlier plays, it may have had political undertones, as there were rumours and threats of civil war in Britain, culminating in the Jacobite rising of 1715. Rowe had completed it, but not yet published it, when he died on 6 December 1718. He is buried in Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey.