Previous book of the term

Michaelmas Term 2022

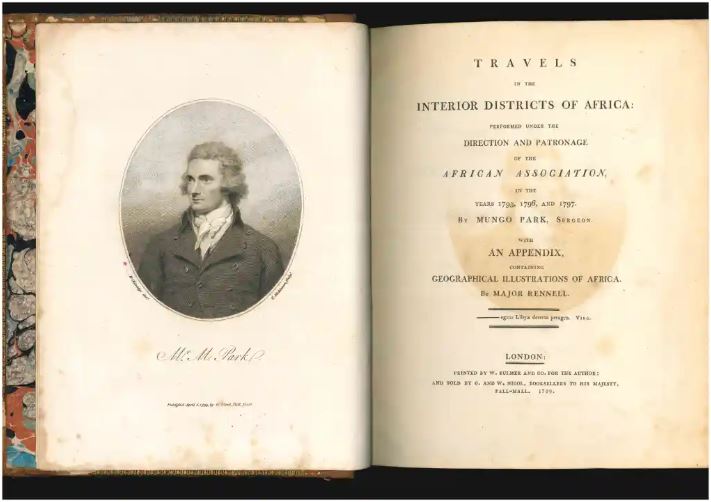

Travels in the interior districts of Africa : performed under the direction and patronage of the African Association, in the years 1795, 1796, and 1797 By Mungo Park

Mungo Park was born at Foulshiels near Selkirk, roughly midway between Glasgow and Edinburgh, in 1771. At the age of fourteen he was apprenticed to a surgeon in Selkirk, and in 1788 entered Edinburgh University to study medicine. In 1792 he moved to London, where his brother-in-law, James Dickson, was a well-known botanist with his own seed and plant business in Covent Garden. Through Dickson, he met Sir Joseph Banks, the great explorer and collector of natural history specimens. Banks arranged for Park to travel as surgeon’s mate on an East India Company ship sailing to Sumatra, where Park collected botanical specimens for him.

The eighteenth century was a time of intellectual revolution; the key to understanding the universe was seen to be human reason rather than divine revelation, and there was a drive to systematize, to discern order in the natural world, and to make knowledge of it as complete as possible. This applied to geography as well: by the 1780s most of the world’s seas had been explored and mapped, but there were still big blank spaces inland on European maps, and one in particular was almost on Europe’s door-step – the interior of Africa.

In 1788, Banks and eleven others founded the Association for Promoting the Discovery of the Interior Parts of Africa, generally known as the African Association. Members were to pay an annual fee of five guineas, and the money was to be used to fund expeditions. Motives for supporting the Association were probably various: it is likely Banks sought to extend scientific knowledge, and to make his own collection of botanical specimens more complete, but others of the founding members were merchants, looking for new sources of raw materials and new markets for finished goods. In particular, they wanted to trace the courses of two of Africa’s greatest rivers: the Nile and the Niger.

The lower reaches of the Nile had long been familiar to Europeans; in the second century BCE, the Greek writer Eratosthenes had sketched, largely accurately, the Nile as far as the confluence of the Blue and White Niles at Khartoum (although the ultimate source of the White Nile was not established until the 1870s). But the Niger, like the city of Timbuktu on its banks, was half-mythical; there were travellers’ reports of a great river south-west of the Libyan desert, but it was usually assumed to be a continuation of the Nile.

By the mid-1700s, it had been established that the Niger was a separate river, but its source and mouth were still unknown. The first expedition sponsored by the African Association was that of John Ledyard, a native of Connecticut, whose plan was to trek west across Africa from the Red Sea to the Niger and follow it to the Atlantic coast, but he got no further than Cairo, where he accidentally poisoned himself while trying to cure a bilious attack. Shortly after Ledyard’s departure, the Association recruited a second explorer, Simon Lucas, whose brief was to head south across the desert from Tripoli, but he was thwarted by tribal wars in the region he was to cross. Their third explorer, Daniel Houghton, set off in November 1790 to travel up the Gambia River as far as he could, and then to find his way, if possible, to Timbuktu and the Niger. He survived a fire which destroyed most of his belongings and a gun which exploded in his hands, and travelled further inland than any European before him, but was then abandoned by merchants whose caravan he had joined, and either starved to death or was killed.

When Mungo Park returned to London from Sumatra in 1794, Banks suggested that he should take on the search for the Niger, to which both Park and the other members of the Association agreed. Park left England for Africa on 22 May 1795.

At first, he followed Houghton’s route up the Gambia. Having reached Pisania, 200 miles up-river, he spent five months there in the house of Dr John Laidley learning the local language, before heading eastwards towards Segou, capital of the kingdom of Bambara, which was known to be on the Niger. His reception was often hostile, as local rulers forbade European traders from travelling inland; when he explained he was not a trader, he was allowed to go on, but still had to make gifts and pay transit duties out of the small stock of goods he had with him, or even out of his own possessions.

Hearing of unrest and possible war ahead of him, he diverted his route to head north, but was captured by Moors, who, thinking him to be not only a Christian but also a spy, tormented and humiliated him, sometimes leaving him without food and water. After three months he was allowed to go on, but with little more than the clothes he stood up in.

He struggled on, and was finally rewarded with his first sight of the Niger, ‘glittering to the morning sun, as broad as the Thames at Westminster’. He reached Segou, but the ruler refused to let him enter (although he sent him some cowrie shells to pay his way). Park carried on, to Sansanding and then Silla, but there, exhausted and almost destitute, decided to turn back.

He followed the Niger to Bamako, struggling through the heavy rains which had now begun. At Bamako he turned west, was robbed of his horse and most of his clothes, regained them, and, severely ill with fever, struggled on to Kamalia, where a kindly Muslim trader undertook to look after him and eventually take him to the Gambia. Seven months later he set out again, this time travelling with a large caravan, and finally reached home, arriving in London on Christmas Day 1797.

His account of his travels, published in 1799, became an immediate best-seller. It is a simple, factual account, and very sympathetic to the native villagers (who were often far more charitable to Park than their rulers). He is also sympathetic to the plight of individual slaves, although he sees no problem in slavery as an institution.

This copy of Mungo Park’s Travels was given to the library by Alice Gillett (née Boycott), who studied Agriculture at Somerville 1958-1961, and went on to become Administrator at St Peter’s School in Mmadinare, Botswana.