Past exhibition

Lockdown Blog April 2020

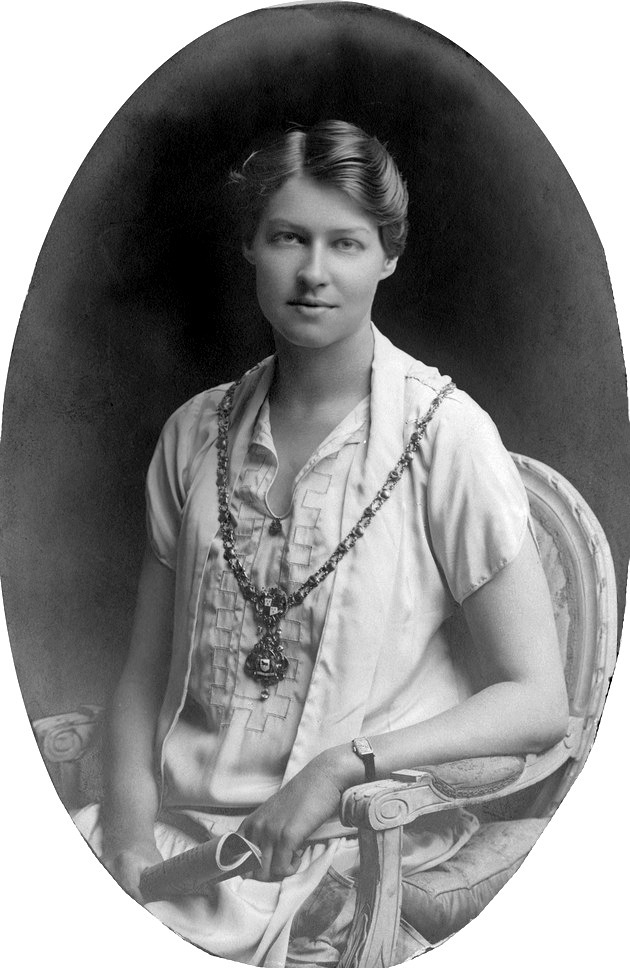

Gwendolen Carter (History, 1929-31)

As the library staff get used to new working environments and arrangements, we will be posting interesting things we come across on the Library blog (Sue will also be keeping up Book of the Month): here is one of Matthew’s working-from-home discoveries – another in a long list of relatively unknown but notable Somerville alumnae.

[This photo was taken as a memento of the day she spent as ceremonial “Mayoress” in Oxford, while her uncle was Mayor]

Carter was born in Canada, and after contracting polio in childhood, spent the rest of her life without use of her legs; this, however, didn’t seem to daunt her – her unpublished autobiography (held along with the rest of her archives at the University of Florida) is full of humour and intellectual vigour.

After completing a first BA at the University of Toronto, Carter took a second degree in modern history at Somerville: she would go on to become one of the founders of African Studies in the United States, president of the African Studies Association and was among the most widely known scholars of African affairs in the twentieth century. As the holdings in Florida make clear, she corresponded widely with the main figures in southern African history, which was her particular field of interest (writing scholarly articles on the first two Apartheid elections in South Africa in 1948 and 1953) – her correspondence with the likes of Nyerere, Khama, Bhutelezi and Biko survives, as does material around her help with the publication of Helen Joseph’s autobiography (interestingly, another Somervillian, Hannah Stanton shared Joseph’s prison cell in 1960). She retired in 1987, aged 81 and there are several scholarships and chairs named after her.

This is the basic biography, but the reason for writing about her is that I have come across an offprint by her in our collection: “Canada and sanctions in the Italo-Ethiopian conflict” extracted from the Report of the annual meeting – Canadian Historical Association, 1940. Before her interest in Africa Carter was interested in international cooperation and security, and this and several other early publications consider the role of the League of Nations, loose coalitions of governments and individual states in prevention and “punishment” of countries engaged in acts of aggression etc. (here she analyses Canada’s proposal for meaningful sanctions, its exposure of the current system and its potential use as a future template). Carter’s interest in politics appears to have been partly inspired by family, but especially by two tutors at her first university, one of whom would go on to be a member of the Canadian cabinet and then Commissioner to Britain in London.

The passion for and engagement with political problems was met and fostered at Somerville: in her autobiography she describes the college’s reputation at the time as “Intellectual, aesthetic, and dowdy”, describes Margery Fry (then principal) as “redoubtable”, and reveals that on their arrival she straightaway abjured all new students to speak out on important issues of the day “from abortion to rearmament”. She also reminisces about the cohort of students with whom she developed lifelong friendships, including Sheila MacDonald (daughter of the Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald), Eirene Lloyd Jones, who was the daughter of a diplomat and later became Baroness White, and Madeleine Oppenheimer, whose father had controlling interests in Anglo-American investment in South African gold mines (it is easy to trace her interests throughout her autobiography, and she appears never to have fallen out of correspondence with the vast number of friends that she made).

She describes her British history tutor Maude Clarke in glowing terms, but reserves highest praise for fellow student Rosemary (Ray) Cochrane, “My thinking was sharpened through the many long evenings we spent debating a range of practical and theoretical issues of the day”, and describes all conversations on such topics before Somerville as “shallow” in comparison.

When we again have access to the physical archive we can see what more we have on Gwendolen Carter, but at a time when we are all physically disconnected it has been a pleasure to get to know more about an interesting and important alumna through the chance discovery of a pamphlet and the University of Florida digitising her autobiography.