Past exhibition

Loggia exhibition November 2023 to February 2024

Mary Somerville through portraiture

In 1879 Somerville Hall (later to become Somerville College) was founded, choosing to name itself after the recently deceased, renowned 19th century polymath Mary Somerville (26 December 1780 – 29 November 1872). The motion was put forward in Council by Mrs Humphry Ward (novelist and, perhaps surprisingly, anti-suffrage campaigner) and seconded by Henry Pelham (President of Trinity and Classicist).

This is an image of the formal Council minute, where this decision was taken, and is part of the College Archives.

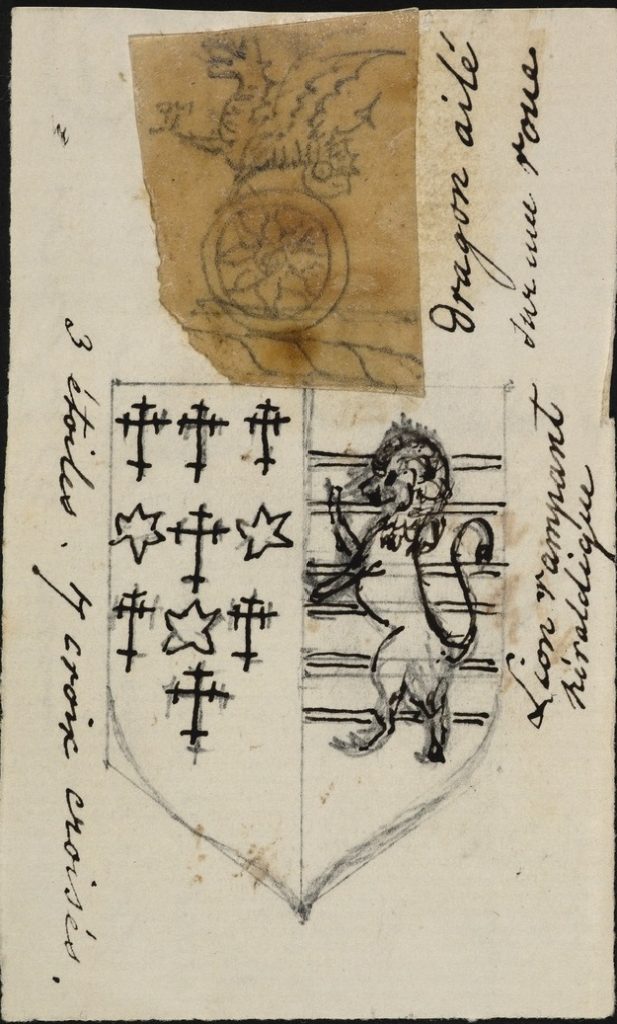

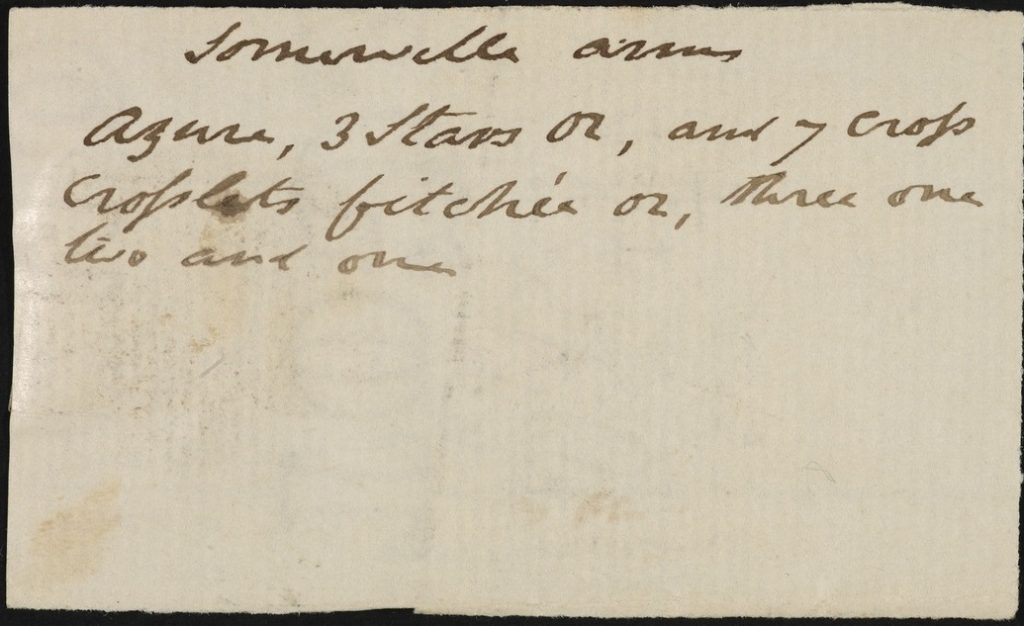

Somerville’s family had donated her books to Girton College, Cambridge in 1873, but soon befriended the new Oxford institution and allowed us to use their family coat of arms and motto (the former adorns the front of the library).

The College’s coat of arms uses different colours to the family, but is otherwise substantially the same: side by side here are (L-R), the current college crest, and a sketch of the family’s by Mary Somerville, with notes in her hand alongside and on the rear (these last two are part of the Somerville papers, which we own but are held for us by the Bodleian).

As well as allowing us to use their coat of arms, the Somerville family have donated paintings, other ephemera and books: these gifts included her shell cabinet (now in the Principal’s Office), a locket containing a lock of her hair, several plaques (see the glass-fronted cabinet for two of these), a pseudoscope – an instrument that reverses depth perception, also in the cabinet (for Thursday 30th only), alongside the ever-so-slightly-complicated instructions! – some of her books and a number of paintings.

Among these paintings are several portraits (including self-portraits), and this 1844 painting by Swinton hangs in the Library loggia.

The portrait hangs above a more recent gift, a painting of Ada Lovelace (credited as being the “first computer programmer”), whom Mary taught maths, and on the other side of the desk is William Somerville, her cousin and second husband.

As well as the Somerville and related Fairfax-Lucy families donating objects, correspondence, books and art, old members and other donors have generously given the college further material relating to Mary Somerville.

Examples of this are the collection of books belonging to Mary and family housed in the Principal’s Office, given by Emma Lambe, and the portrait of Ada Lovelace

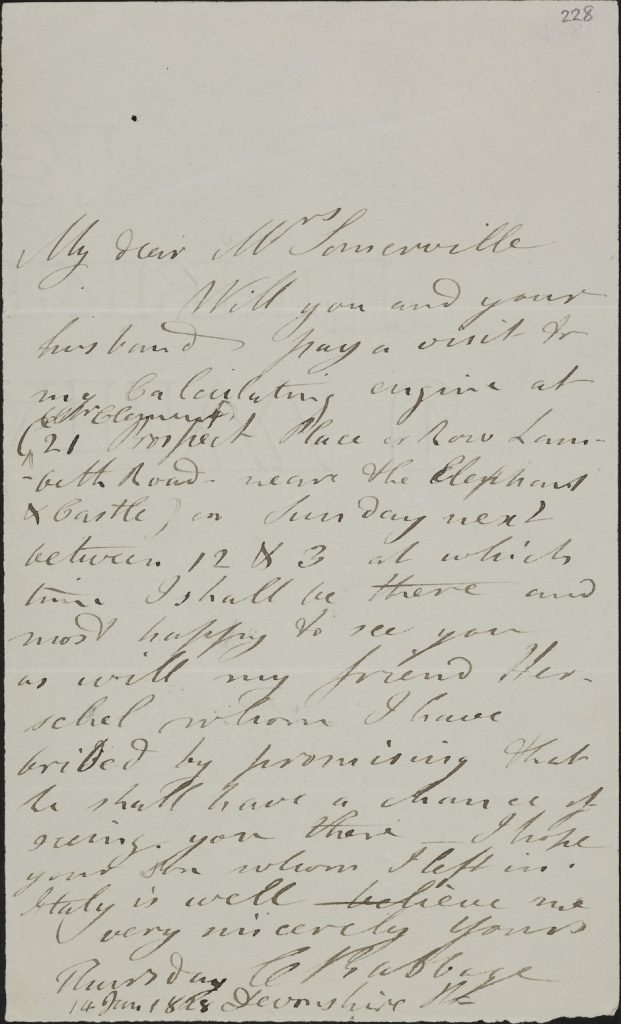

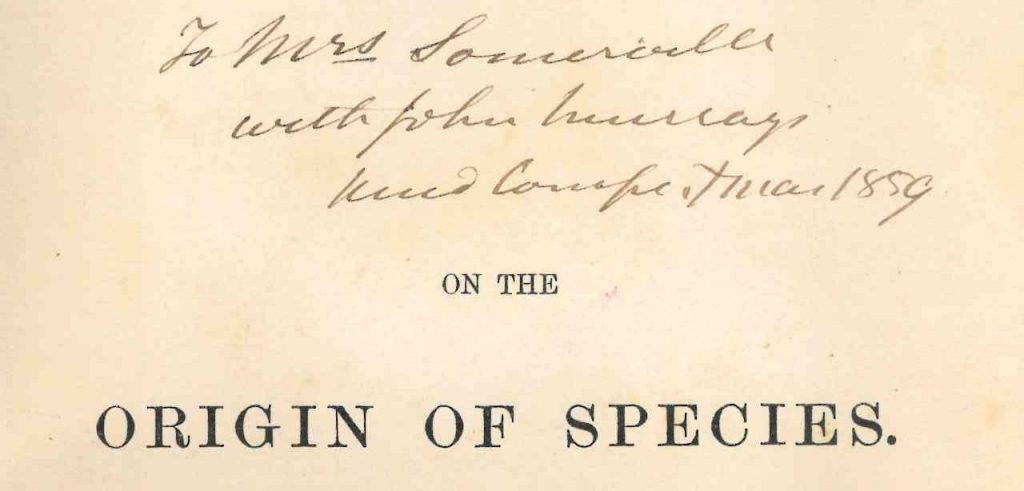

The portrait of Lovelace also highlights the many connections with notable people of the day that Mary had: this letter is from Charles Babbage inviting her to witness his ‘Calculating Engine’ (Lovelace also worked with him), but we also have her inscribed copy of Darwin’s On the origin of species (upstairs in the John Stuart Mill Library for Thursday 30th November only) and correspondence (held at the Bodleian) between her and the Herschels, the artist Turner, Ampere, Faraday, von Humboldt… and the list goes on to include a veritable host of “celebrities”, including many scientists.

The portraits

as a young woman

by John Jackson

This can be seen in situ in the dining hall

gift from Charles Fairfax Murray through Sydney Cockerell, 1911

Mary Somerville

by Francis Leggatt Chantrey, 1840

This can be seen in the Mary Somerville Room in House

gift from Sir William Bousfield, 1887

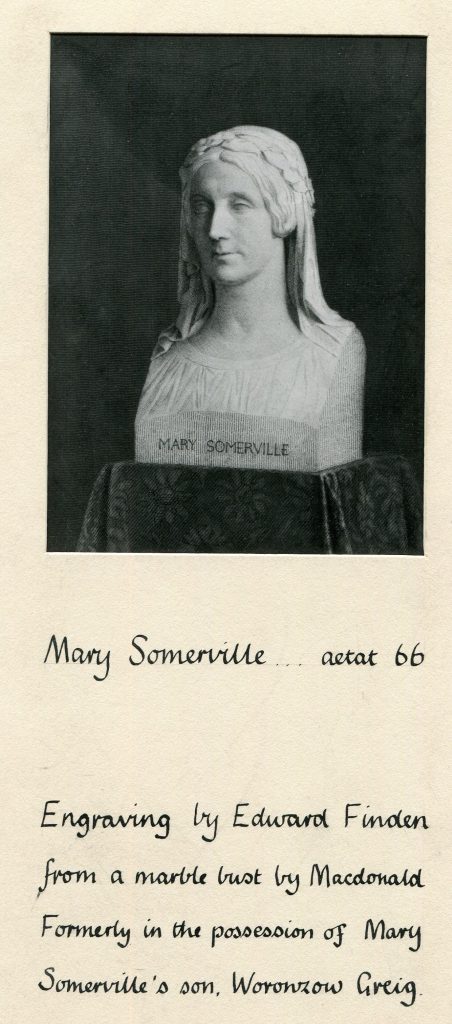

Mary Somerville by Lawrence Macdonald, 1844

Having moved around a bit, this bust currently lives in Green Hall in House

gift from Major Fairfax-Lucy, 1961

This picture hangs at the foot of the staircase leading to the dining hall

gift from Lieutenant Colonel J. Ramsay Fairfax, 1958

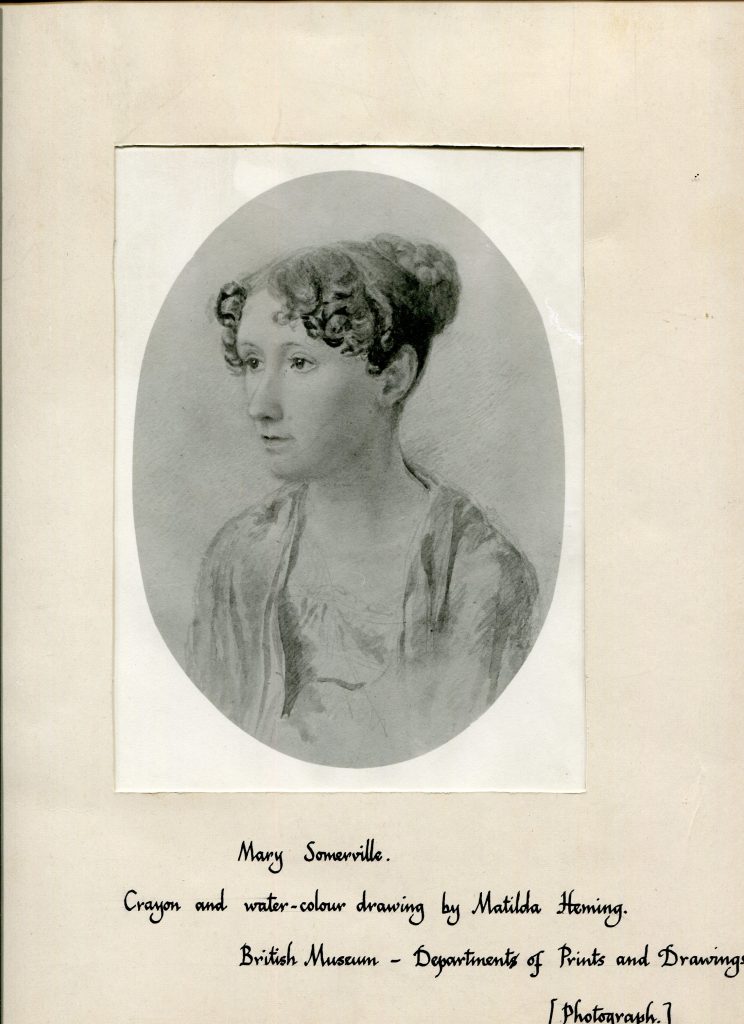

As well as these portraits, there are many other likenesses of Mary Somerville around (if further attestation of her contemporary and lasting fame were needed), including at the National Portrait Gallery and the Courtauld Institute.

The visual representations of Mary indicate the high regard in which she was held, but the college also possesses (although the collection is stored at the Bodleian) correspondence to, from and about her, as well as her own “autobiography”, Personal Recollections (edited by her daughter Martha and published in 1873), a copy of which is on display in the glass fronted cabinet, and open at the pages where she describes her (self) education in the physical sciences and the very first award she won for her work.

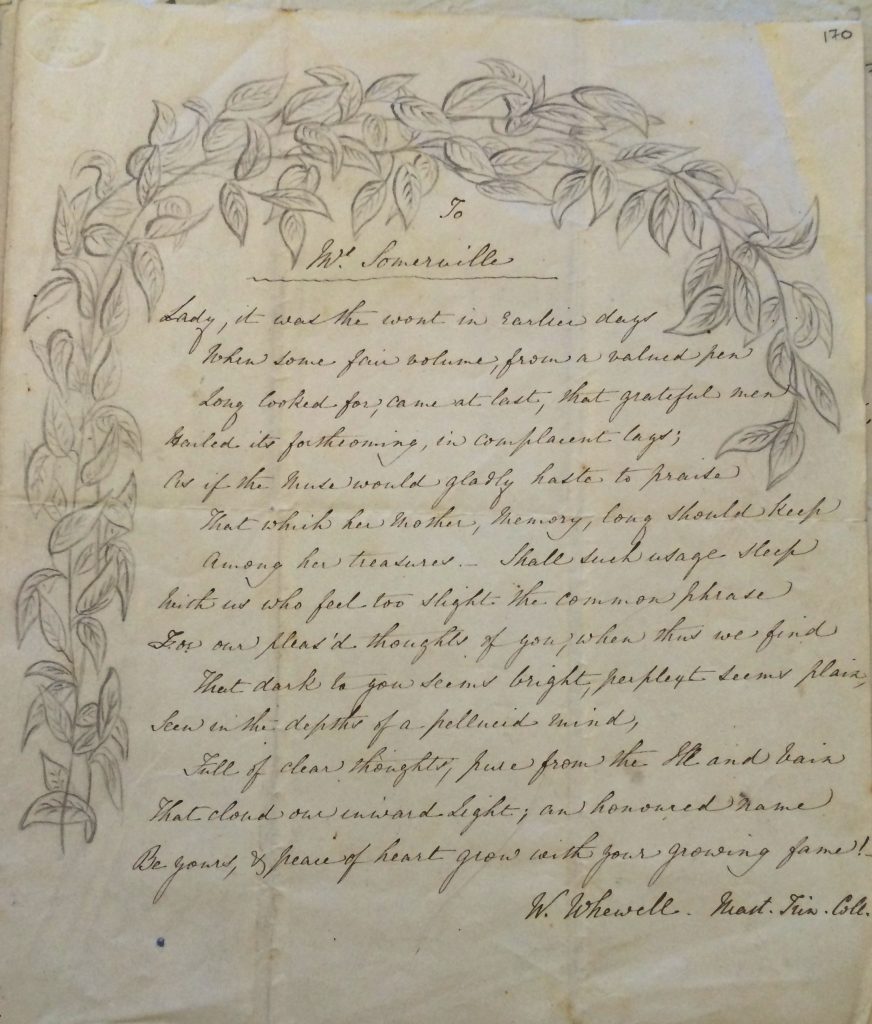

William Whewell (head of Trinity College, Cambridge), who would write the article (on display in the glass fronted cabinet) using the word “scientist” for the first time, in reviewing Somerville’s On the connexion of the physical sciences, was a frequent correspondent – the book is open at the start of his review, where he calls her handling of the material “masterly”. Reproduced here is a version of the sonnet (included in the review) that he wrote in praise of her.

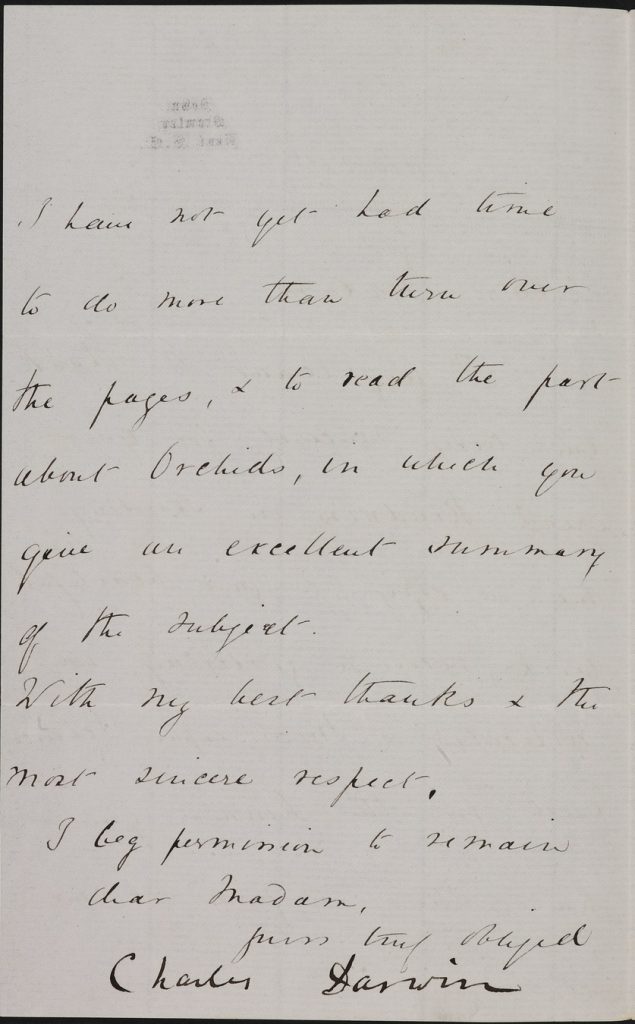

As well as Whewell’s review of her work, the epistolary record is revealing of both the depth and breadth of her knowledge: to the left here is a letter from Charles Darwin, complementing her astute observations on orchids.

Mary’s copy of Origin of species, inscribed by him to her, and featuring marginalia which would suggest that she read and marked up passages for commenting on in her correspondence with him, is on display in the John Stuart Mill Library (Thurs. 30th Nov. only) (inscription below)

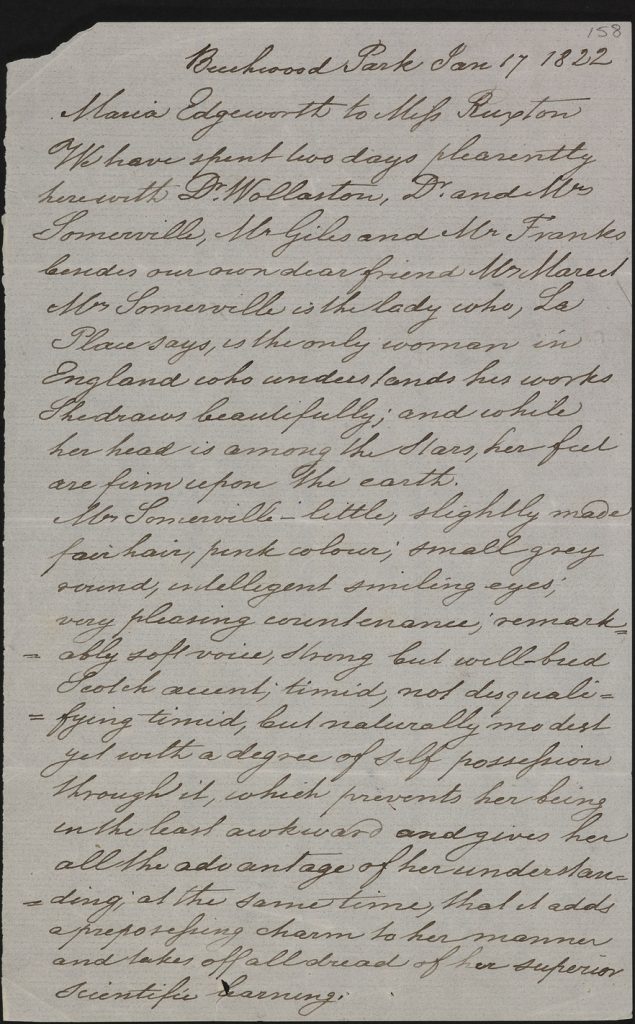

The author Maria Edgeworth also described Mary in a letter to a friend (shown above right), adding that La Place said that she was “the only woman in England who understands his works”. Mary would go on to condense and translate his Mécanique celeste as Mechanism of the heavens, her first book, published aged 51, and which made her name.

Copies of a different Laplace (Mill’s copy) and Mary’s version are on display upstairs in the JSM Library (Th. 30th Nov. only)

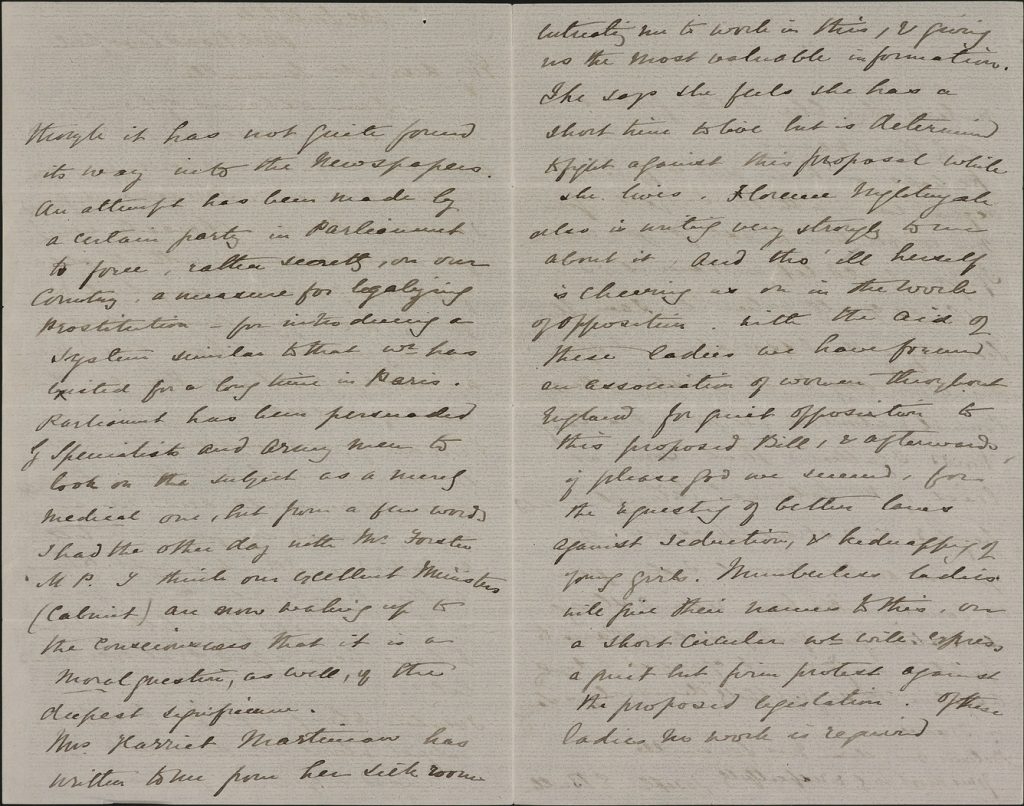

If 51 seems a trifle older than you might expect for a first publication, it is worth being mindful of the battle for education that Mary fought: it took a great amount of perseverance to be able to eventually study mathematics and then higher branches in the sciences. Personal Recollections contains many anecdotes on the topic, but it also paints a portrait of a woman at home in society and who mastered more domestic skills as well as painting, music and dancing (deemed by her family as acceptable things to learn). The correspondence further backs this up: she conversed knowledgeably on science with the Herschels, Babbage, Faraday and Darwin, but also on politics and social issues – below is a letter from Josephine Butler talking about a proposal to legalise prostitution

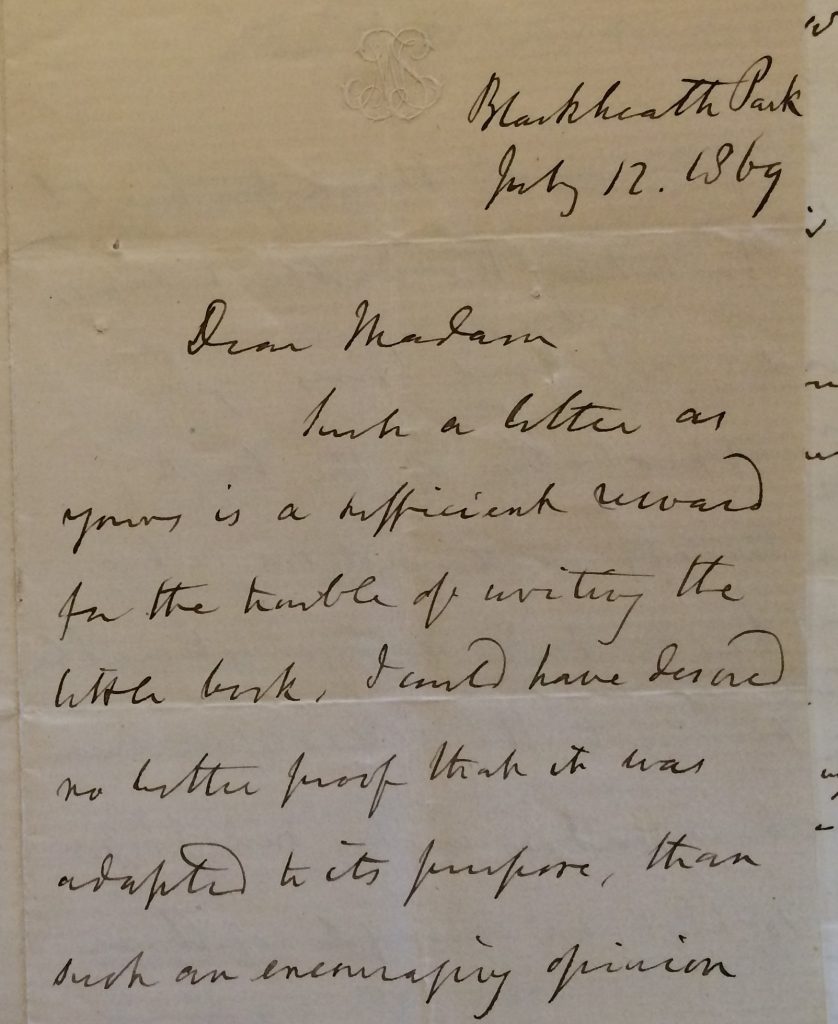

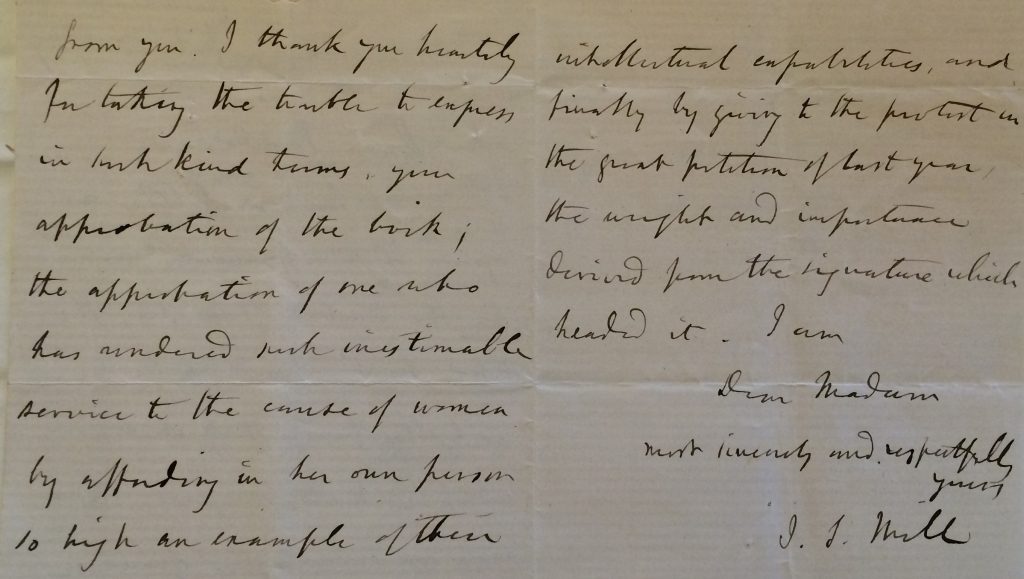

Mary’s engagement with social issues included suffrage: in the papers at the Bodleian are documents relating to her donations to the Women’s Suffrage Society, as well as a lengthy correspondence with John Stuart Mill. Below is the letter in which he thanks her for being the first signatory on his 1866 petition to Parliament for women’s suffrage: we know that Mary respected Mill and his opinions, not just from the correspondence and her agreeing to be a signatory to the bill, but because she also chose to quote this letter in full in Personal Recollections (p.345 of the edition on display on the stand)

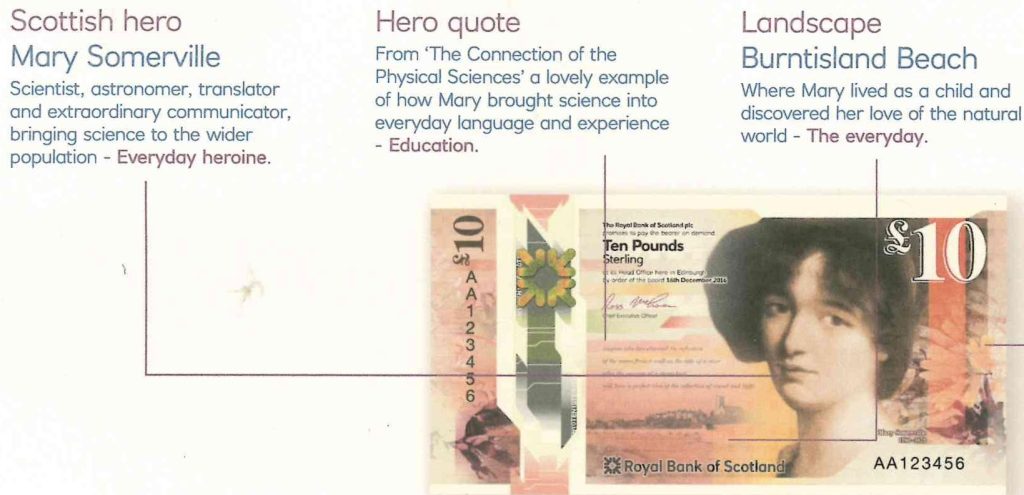

This exhibition has sought to highlight the preeminent position of Mary Somerville as a figure in 19th century science and society, through the many and varied portraits (both artistic and literary), but it is worth mentioning that academic interest in and work on her continues: the college held a transcribe-a-thon of her letters earlier this year, and academic and alumna Brigitte Stenhouse continues her studies of Mary’s contributions to mathematics (see the selection of books from the library’s collection to your right). In addition the Royal Bank of Scotland chose Mary to be the face of their new £10 note, using our John Jackson portrait in Hall as the image (framed copies can be seen in the Mary Somerville Room in House)