Past exhibition

Loggia exhibition November 2019

Trowelblazers: Somerville’s groundbreaking anthropologists

Pioneers and philanthropists: Amelia Edwards and Emily Kemp

Amelia Blanford Edwards (1831-1892)

A founder of the Egypt Exploration Society (through which she met Somerville’s first two Principals Miss Shaw Lefevre and Miss Maitland), Edwards travelled widely (notably in Egypt), collected objects, and documented her findings in both writing (including the immensely successful 1000 miles up the Nile) and painting. She bequeathed her general library to Somerville, for which a special room was constructed at the eastern end of the building:

“It is the library of a person interested in many subjects, who read everything that came her way and made the utmost of the comparatively limited opportunities of a woman of the mid-Victorian era. One understands the more easily as one makes acquaintance with her books, why Miss Edwards was anxious to bequeath a possession so precious to her as her library to a College which should give to the women of a later generation much that she was able to attain only with great difficulty and much that never came within reach.” SSA Report for 1907

As well as the important collection of books, Edwards left the college her watercolours (many of which can be seen hanging in the Library), letters between her and other notables of the period (including authors who donated inscribed copies of their books to her) and a collection of Egyptian, Greek and Roman pots, one of which can be seen here.

On display is a terracotta figurine of a comic actor, from the Hellenistic or Roman period (catalogue number SOM ABE 30)

Emily Georgiana Kemp (1860-1939; Somerville 1881-3)

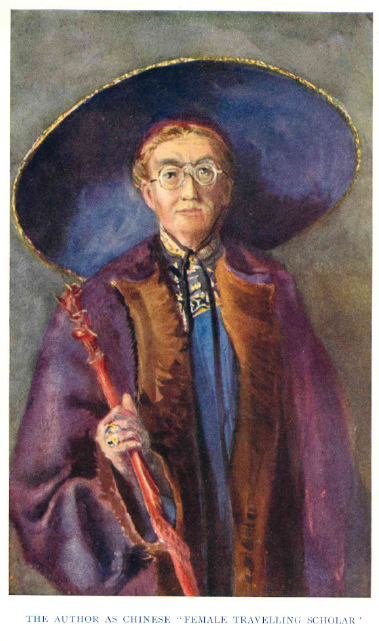

One of Somerville’s first students, who continued her studies at the Slade School of Art, Kemp travelled widely in Central and East Asia, and documented her travels in several books, illustrating them herself. In the prefaces to The face of China (the frontispiece of which, showing the author in Chinese garb, can be seen here), The face of Manchuria, Korea and Russian Turkestan and Chinese mettle she describes how she was repeatedly told how dangerous it was to travel in such areas, and that she was warned off doing so.

One of the rewards for undertaking and documenting her travels (as well as becoming a successful author) was to be the first woman awarded the prestigious Grande Médaille de Vermeil by the French Geographical Society, for Chinese Mettle (the copy of which she donated to the library is open here).

The watercolours from which the illustrations in The face of China are printed are soon to become part of Somerville’s collection (having initially been donated to the Eastern Art department of the Ashmolean Museum) but they are a small gift in comparison to the most controversial of her donations to the college, that is the chapel:

“Emily Kemp’s gift to the college in 1932 of a chapel which might be a ‘House of Prayer for All Peoples’, prompted as it was by long practical familiarity with Buddhism and the other religions of the East, was hardly incompatible with the founders’ objectives. But, despite its unconsecrated and ecumenical status, the chapel has always been a focus of controversy in college” (P.A. Adams Somerville for women, p.354)

Funding and fieldwork: Barbara Freire-Marreco and Maria Czaplicka

Barbara Freire-Marreco (1879-1967; Somerville Research Fellow 1909-13, Mary Ewart Travelling Scholar 1912)

After the untrained Edwards and Kemp, Barbara Freire-Marreco was part of a flourishing of anthropology at Somerville in the decade leading up to the Great War, that showed the value of funding scholars in the subject. This funding enabled the increasing professionalisation of the science and development of its practices.

She was the third Somerville Research Fellow (later renamed the Mary Somerville Research Fellow), and the first recipient of the fund set up from the bequest of Mary Ewart, which enabled her to continue her research into the Pueblo peoples of the Southwestern area of the USA.

One of her offprints on the topic is on display here, along with an extract from one of her letters sent back to college detailing the difficulties, but also (as here) the joys of her research, and the relationships she developed during her time in the field.

The other item on display is the Principal’s cup (with accompanying letter), presented by Miss Freire-Marreco to the Principal in 1914, indicating some of the appreciation that the early recipients of these scholarships and fellowships felt towards the college.

Marya Antonina Czaplicka (1884-1921; Somerville 1911-12, Mary Ewart Travelling Scholar 1914)

Maria Czaplicka was another one of Somerville’s early anthropologists, taking her Diploma in 1912, and her case highlights just how very precarious the position of researchers and those undertaking anthropological fieldwork was in the early part of the 20th century.

Czaplicka knew Miss Freire-Marreco and applied for the Mary Ewart Scholarship, in hopes of using the funding to go to Siberia (see the typed application letter), and like Freire-Marreco she (having been successful in her application) wrote back to the college, reporting on her work and the steps she was taking to ensure that her research materials and finds made it back.

The envelope for one of these letters (addressed to Miss Penrose in both Russian and English) is also reproduced here and encapsulates how many hands a simple letter had to go through to get to England. Some of this was due to the political situation in 1914, and the letter on display shows her deliberations about what to do with her collections after the outbreak of war: she considered leaving them in Moscow, and (as the letter shows) she made as much use of any connections she had to ensure the survival of her work.

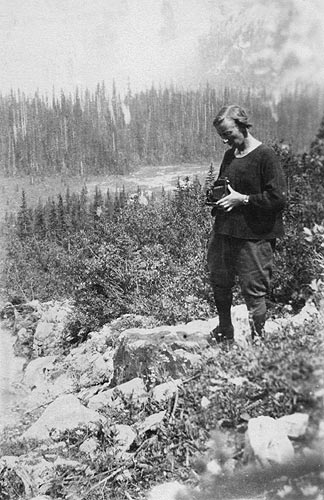

Her collections did make it back and she published an account of her work in My Siberian Year (1916): the copy she gave to Somerville is on display here and open at the dedication from her to the college, alongside a reproduction of the photographic portrait which is also the frontispiece of the book.

After returning to England she held a 3-year lectureship in anthropology at Oxford and, when this finished, moved to the University of Bristol where, when she failed to receive more funding, she took her own life in 1921.

Barbara Freire-Marreco bequeathed money to the college to set up the Marya Antonina Czaplicka Fund, which started in 1971 and is still open to assist any student of the ancient world, anthropologist or scientist who may wish to attend a conference or similar meeting abroad.

Professionalisation and lasting impact: Katherine Routledge and Beatrice Blackwood

Katherine Scoresby Routledge (1866-1935; Somerville 1891-5)

Having studied Modern History at Somerville Katherine Routledge soon followed up on her interest in anthropology by travelling abroad, first to South Africa to investigate the resettlement of single working women there, and then published a book on the Kikuyu people of East Africa with her husband in 1910.

Following on from this she was part of an expedition to Easter Island in the Pacific: the journey there took over a year and is chronicled, along with the rest of the expedition, in her book The mystery of Easter Island (1919), open here at the title page and frontispiece.

Routledge had no previous technical archaeological expertise, but went with instructions from Dr Marrett (who had also encouraged Maria Czaplicka) and the work undertaken on the expedition is still regarded as important today.

Despite her desire to rewrite the text to include more technical details of the archaeology, this work and the ethnographic material contained therein, have formed the basis for much subsequent work in the field and without which our knowledge of the Rapa Nui would be very limited.

Routledge, like the other Somervillians in this exhibition, retained a connection with the college and bequeathed a sum of £500 to commission a posthumous portrait of Miss Maitland.

Beatrice Mary Blackwood (1889-1975; Somerville 1908-12)

Beatrice Blackwood read English at Somerville and then took a distinction in the University Diploma in Anthropology (like Maria Czaplicka, a contemporary of hers at Somerville) in 1918. After this she became the departmental demonstrator in anatomy, then received funding to do anthropological fieldwork in North America and on her return became demonstrator in ethnography, which position then became associated with the Pitt Rivers, where she would remain for the rest of her life.

As this varied educational background implies, the hallmark of her anthropological publications is the combination of social anthropology, material culture, and technology, reflecting her ability to combine methodological approaches. Her work on the Kukukuku of the Upper Watut is on display here, and is based on funded fieldwork; alongside it is a picture of several tribesmen and her kitten: in the region, where few locals spoke the lingua franca of pidgin, the cat’s antics proved essential in breaking down the barriers of communication between her and the warriors (photograph courtesy of Pitt Rivers Museum).

The other display is one of her own illustrated plates from her 1935 book Both sides of Buka Passage.

Her expert fieldwork was rewarded with the Rivers Medal of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1943, but perhaps her most lasting contribution to anthropology is the comprehensive classification system developed for the cataloguing of the collections of the Pitt Rivers Museum, which was published for use in other museums in 1970.